Costs COVID Interagency Collaboration May 10, 2021

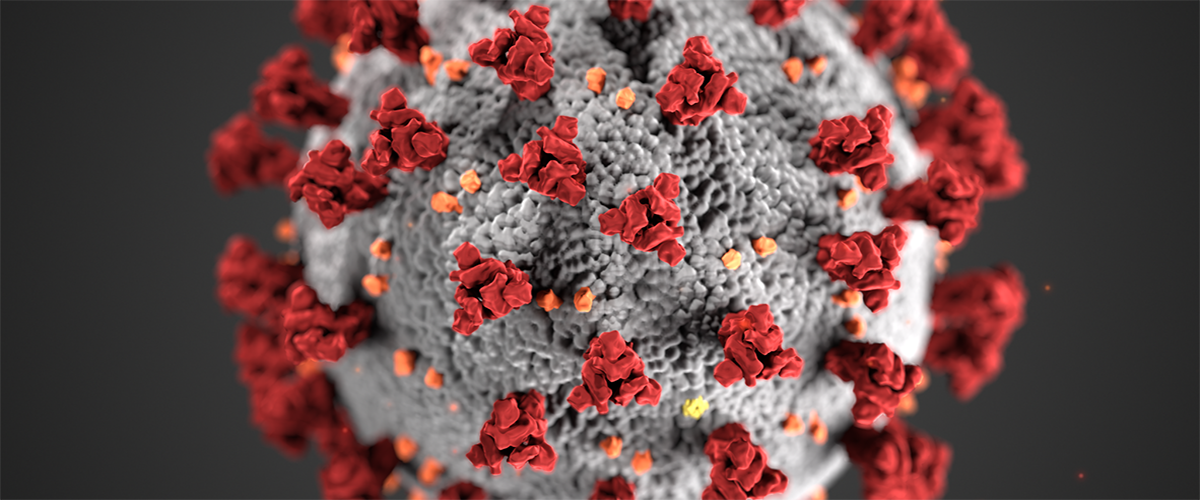

The Safety and Justice Challenge has reduced jail populations around the country. But it is clear that racial disparities need more focus as part of the work. And COVID-19 made that clearer than ever.

As strategic allies to the Safety and Justice Challenge, my organization brings people with experience of incarceration to the table. Our view is that the people closest to the problem are the best placed to fix it. You would not have a conversation about women’s reproductive rights without women at the table. And it is the same with criminal justice reform. It is important that these are the people driving these conversations. The people most impacted by the injustices in the system should be at the table to inform the policy and work being done.

Formerly incarcerated people saw how COVID-19 once again laid bare structural inequities in the jail system. Black and Brown people stayed in jail for longer than White people during the pandemic. And they died of COVID at disproportionate rates in our nation’s jail systems.

We have seen incarcerated people’s lives at risk during previous crises. During Hurricane Katrina the Louisiana authorities looked after stray cats and dogs fast. Meanwhile they left people to fend for themselves in Orleans Parish Prison. They left them for days without food, water, or adequate ventilation. Then they moved them to a bridge with the flood waters rising all around. In New York, there was no evacuation plan for people on Rikers Island during two hurricanes. Incarcerated people in New York were also charged with making hand sanitizer — while still barred from using the sanitizer themselves, since it had been designated as contraband.

State emergency plans include labor by the detained, including digging graves. That happened in New York during COVID-19. Or putting out wildfires. That happened in California. But they don’t include planning to save their lives.

We show that Black and Brown people are disposable in the United States when we fail to plan for emergencies. Our society, our elected leaders, and those in power are neglecting the safety of millions. This type of systemic racism is the result of the generational legacy of slavery. And it is critical to decarcerate the United States by changing policies.

Many people spend time in jail while presumed innocent, before they go to trial. And yet too often, COVID-19 handed them a death sentence.

For the last nine months we have been running a #JustUs campaign. It is calling on legislators to enact proactive solutions for emergencies. Particularly for incarcerated people. One result: On September 30, Senator Tammy Duckworth introduced a federal bill to protect incarcerated people during disasters. And we have introduced a legislative roadmap for the next three years. One of our big recommendations is to pass Senator Duckworth’s bill.

Likewise, at the local level we are training formerly incarcerated people to speak up and get legislation passed. The #JustUs social media campaign features advocates in ten key locations — Alaska, New York, New Jersey, Michigan, South Carolina, Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Wisconsin — who have been incarcerated themselves, and who are demanding that their representatives create official plans to protect those in jails, prisons, and correctional facilities in the event of disasters.

It could be the difference between life and death, particularly in a world with increasing natural and man-made disasters. We need emergency management plans in place yesterday.

Our campaign’s policy recommendations cut across the criminal justice system, involving everyone from courts to jails to law enforcement:

- Bring in experts in the field of emergency management and public health to create plans that anticipate every emerging disaster.

- Empower the corrections agencies to act without legislative or judicial intervention after declaration of a pandemic or crisis.

- Require corrections agencies to evacuate when necessary to decarcerate, utilizing public health triage mechanisms according to highest risk, i.e. pregnant women, people with respiratory illnesses, those over 50, and those within two years of release.

- Provide medical and humane treatment to those remaining, by providing access to the necessary safety precautions and forbidding the use of solitary confinement as a means of meeting those requirements.

- Halt transfer of jail intakes into state correctional custody.

- Require judges to use alternatives to incarceration when possible to avoid detention at all costs.

- Ensure that no one is detained because of inability to pay, including cash bail or any past debts.

- Stop all arrests for technical violations and eliminate in-person reporting and drug testing

- Replace arrests with law enforcement citations in lieu of arrest.

- Build a strong network of reentry services to transition people and ensure their success and safety after incarceration.

- Create an independent oversight mechanism and reporting to legislatures for enforcement and compliance.

The full list of recommendations and our comprehensive platform can be found here.

People can get involved by demanding that their elected officials have emergency plans in place to release our country’s and our community’s most vulnerable immediately in the event of future disasters. Your involvement can expand this platform to the other 40 States and the District of Columbia.

To learn more and join the #JustUs campaign, visit: https://jlusa.org

—Ronald Simpson-Bey is Director of Outreach and Alumni Engagement at JustLeadershipUSA