Community Engagement Racial and Ethnic Disparities June 17, 2022

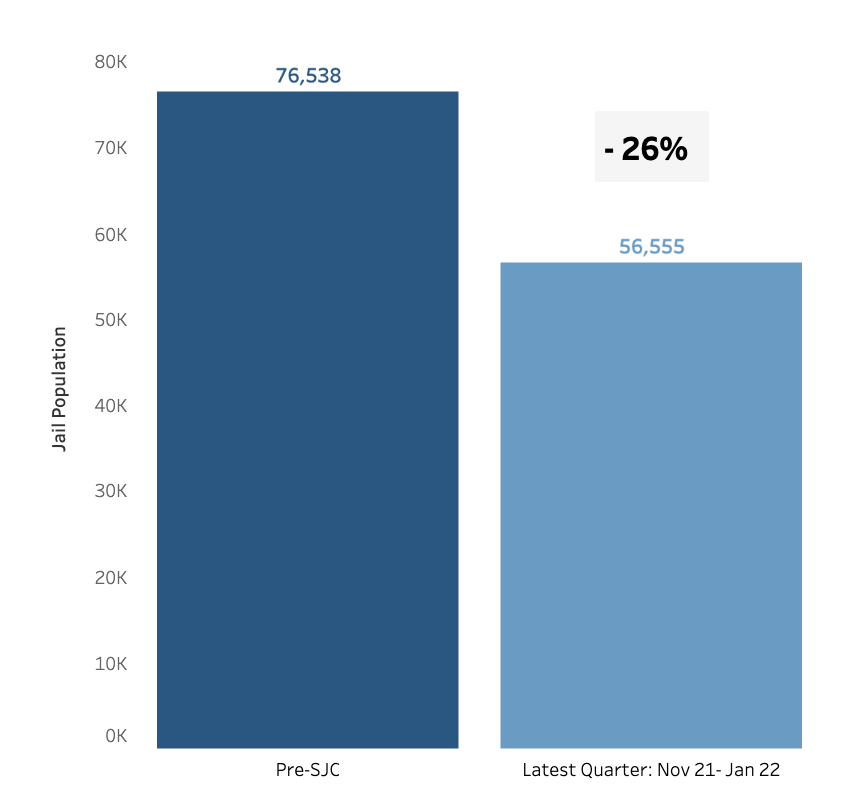

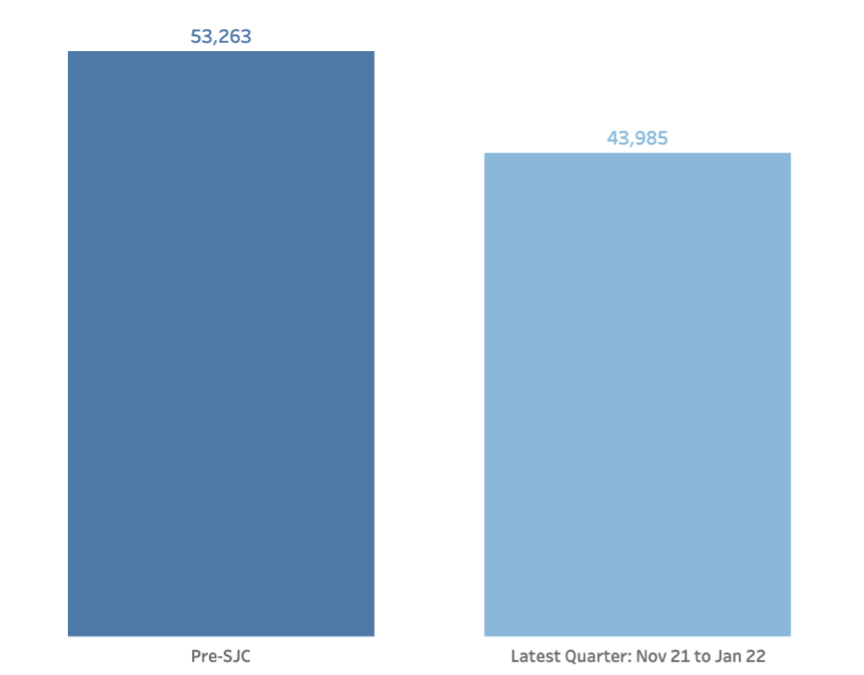

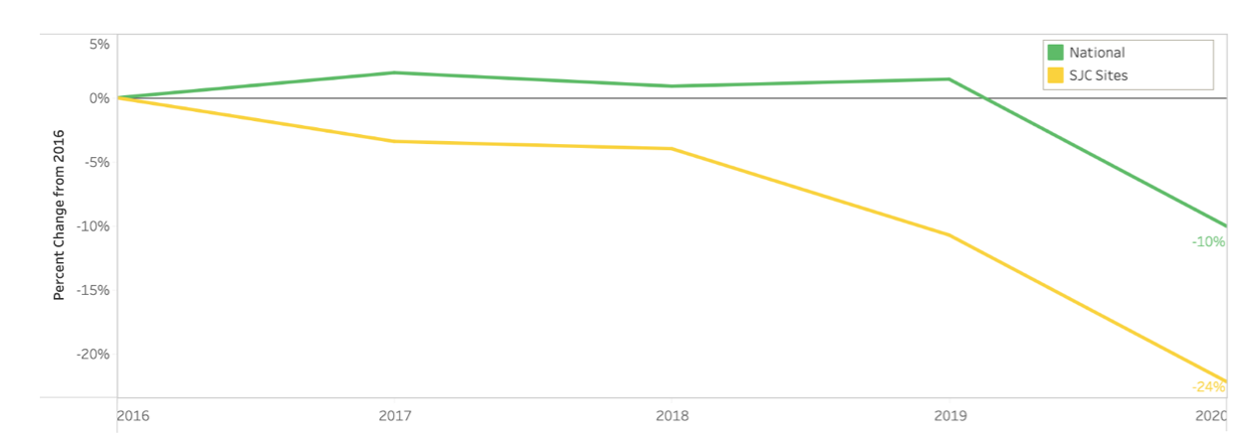

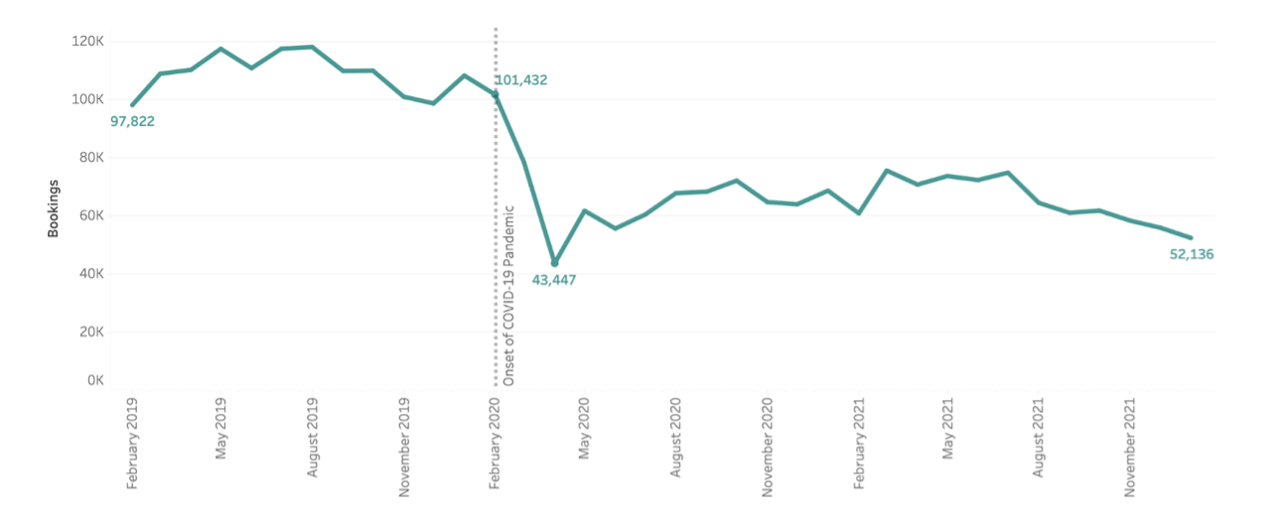

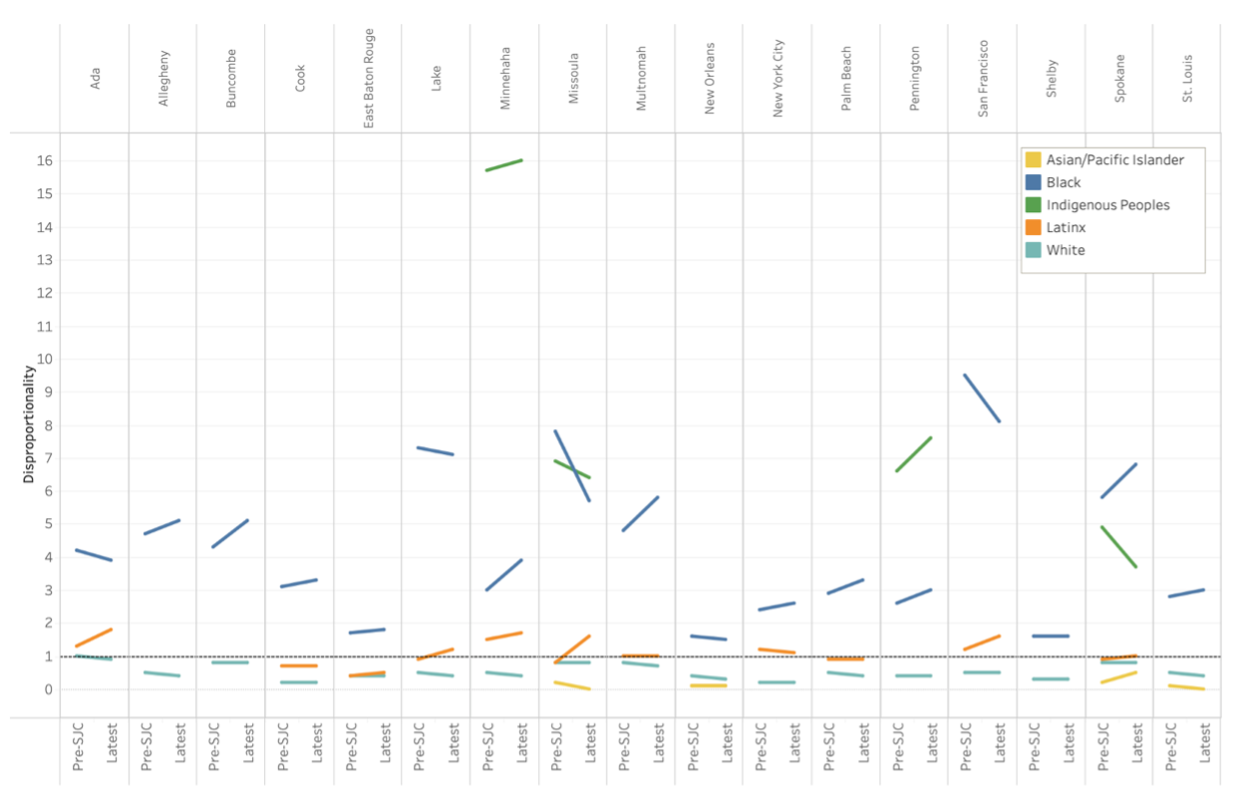

Cities and counties participating in the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) significantly reduced their jail populations over the past few years – both prior to and since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite that progress, racial and ethnic disparities in jails persist. You can read more about the data here.

In January 2022, the Challenge deepened its commitment to learning and investing in more intentional and effective strategies to eliminate institutional and systemic racism within the justice system. It selected four jurisdictions to join a new Racial Equity Cohort based on proposals that explicitly focused on racial and ethnic equity in the criminal justice system.

The four cities and counties selected to participate in the Racial Equity Cohort were Cook County (IL), New Orleans (LA), Philadelphia (PA), and Pima County (AZ). Their proposals centered lived experiences of Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other people of color. They also emphasized the SJC Community Engagement Pillars of authenticity, accessibility and transparency, respect for diversity, and commitment to ongoing engagement. Participation in the Racial Equity Cohort provides communities with training and technical assistance focused on racial equity and authentic community engagement, peer-to-peer support from other cohort members, and qualitative and quantitative data and analytic support.

Nearly six months into the project, we spoke to people in Chicago, New Orleans, and Philadelphia about the progress of the initiative so far.

Sisters With a Goal Research Budgets in Philadelphia

The author of three books, Reverend Dr. Michelle Anne Simmons is the founder and Executive Director of Why Not Prosper, Inc., a grassroots Philadelphia nonprofit devoted to helping incarcerated women make a smooth transition back into society. Michelle has lived experience of incarceration and overcoming addiction, achieving sobriety in 1999. In 2014, she helped form and implement a pilot program for women escaping trafficking. Since then, she has created several services supporting Philadelphia women including graphic arts programs, leadership advocacy programs helping women recognize their leadership abilities, domestic violence programs, and women’s advocacy workshops. She received a full and unconditional pardon for her conviction in 2015.

Michelle’s team of Sisters With A Goal (“SWAG” for short) is leading an exploration into justice investment in Philadelphia through a participatory action research project—a kind of research project where people who are traditionally subject to research are viewed as experts in their own experience and stories, and are involved in the question development. They are working with academics at Bryn Mawr College on the project. As part of the project the Vera Institute of Justice worked with Philadelphia’s Office of the Director of Finance to produce an analysis of criminal justice spending. Based on that analysis, Michelle and her sisters are coming up with deeper questions for further research around racial and ethnic disparities.

“We’ve all been involved in the criminal justice system,” Michelle said. “Now we’re leaders in the community. And we’ve not historically been involved in looking at the data or the budgets. If you look at the budget with a regular lens, you might not see what we’re seeing. But if you look at the budget with an equity lens and you look at how many people are arrested and where the money is being spent, it gives you a whole different picture. And we’re also having an intentional dialogue around that as we come up with a pilot program to do things differently.”

The goal is to look at reinvesting some of Philadelphia’s criminal justice dollars into a community-based alternative under a pilot program suggested by the community, said Lisa Varon, the Interim Deputy Director in the Office of Criminal Justice at the City of Philadelphia, which is also a partner in the research project.

“This is an example of people closest to the issue looking at the possible solutions themselves, and we’re excited to learn from the ideas coming from the community,” Lisa said. “Government can’t solve the racial equity issue on its own, so I do appreciate that we’ve had the opportunity to partner with the community to come up with solutions.”

Meanwhile, the city is also partnering with the Center for Carceral Communities, an initiative of the University of Pennsylvania, to work collaboratively with neighborhoods in West Philadelphia to help people with a history of incarceration re-engage with the community. In partnership with the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office, CCC will deliver services as part of a diversion program pilot, providing free, evidence-based psychosocial services to participants.

Intentional Conversations in Chicago

Kim Davis-Ambrose is the Community Engagement Coordinator for the Justice Advisory Council in Cook County. She describes Chicago’s history in Dickensian terms: “We absolutely see Chicago as the tale of two cities,” she said. “And I’ve lived and breathed that because I grew up in public housing. So, I understand how we got here.”

She has been working in partnership with Everyday Democracy as technical assistance providers on a dialogue-to-change process in three of Cook County’s most vulnerable communities based on data about recidivism, violence, and disparities.

“We’ve started to have conversations intentionally to hear from community members what their feelings were toward the criminal justice system, what their feelings were, and what they think needs to be done to improve the system,” she said. “And how we could best partner with community to continue to have their voices at the table in a shared power space.”

As part of the racial equity cohort, Kim’s team is working in six communities and identifying people who would like to become fellows and be paid a stipend so that their voices can be part of ongoing efforts to reform.

“We take for granted that people understand the criminal justice system, but that’s not true,” she said. “And we want people to be able to continue to educate the community about what the different wheels are of the system and how they can continue or start to become involved.”

The fellows will go through a rigorous trauma-informed curriculum covering violence intervention, restorative justice, community organizer facilitation and training.

“We want them to be equipped to go into the community and continue that dialogue to change process,” Kim said.

Derrick Dawson is a National Organizer and Workshop Facilitator for Crossroads Antiracism Organizing and Training in Chicago. As an Equity Cohort Partner to the Cook County Racial Equity Cohort, he is focused on addressing long-term systemic and institutional racism as a factor in who goes to jail and who does not.

Right now, Derrick is working to identify fellows within ten organizations working on the ground on these issues, who will be paid a stipend to participate in a training program. He will also identify ten internal system representatives across criminal justice offices for the same program, to provide a collaborative learning experience.

The goal is to give the fellows a shared language on long-term systemic and institutional racism to take back to their everyday work. The big challenge, Derrick said, is helping people to see how their day-to-day work fits into the bigger picture so that they are more empowered to advocate successfully for change.

“Many organizations dealing with jail and justice and men and women going to jail get consumed with issues of the day,” he said. “Feeding, housing, getting jobs–those very important things. It takes a lot to get to the deeper issues of systemic racism when people’s lives are at stake every day.”

In that context, building an understanding of long-term systemic racism is crucial if Cook County’s justice system can move forward, Derrick said. From colonialism to slavery, “the jails would not exist today if it were not for systemic and institutional racism,” he said. “The more folks we can get to think about these issues systemically and institutionally, perhaps the next generation will have less of a slog than we have. Otherwise, we will be in the same place 20 or 30 years from now as we are today.”

Supporting Community Engagement in New Orleans

New Orleans convened an Ethnic and Racial Disparity Working Group in 2020 to set goals to reduce justice system involvement for people of color. Half of the group were government agency staff and half were community members, and it analyzed disparities across the justice system. It came together quickly with commitment from all players and published a report in just 10 months with concrete recommendations supported by all the agencies and community members involved. The report recommended regular and authentic engagement by system stakeholders with system-impacted individuals. The group also recommended making grants to BIPOC-centered organizations to try innovative approaches to criminal legal system prevention and reform efforts.

New Orleans’ racial equity cohort is taking the next step in that process with the creation of a Blueprint for Racial Justice and Criminal Legal System Reimagination through data-driven analysis and community engagement. The City of New Orleans is partnering with nonprofit Total Community Action on the community engagement work.

“Our mission is to reduce poverty,” said Glenis Scott, Director of Community and Energy Services at Total Community Action. “And oftentimes when you’re working in the judicial system, both the adult and juvenile judicial system, we find it’s important to work with low-income families to ensure that there’s a path forward. When you’re looking at reentry from the judicial system or at housing funding, or at low-income food and energy programs, what we’re really trying to do is help people build a better life for themselves. Having the funding available to help educate people and provide supportive services is paramount if we’re going to be able to change what is happening inside the system right now. And that’s what the voice of the community is talking about. These systems are interconnected.”

New Orleans is also looking to convene leaders in the system around what the future looks like from a policy perspective, said Kate Hoadley, Racial Justice Program Manager at the City of New Orleans.

“The country has come to terms with the need to rectify systemic racism,” she said. “But right now, in New Orleans, we are seeing a rise in community harm. Gun violence is up and many people are proposing different solutions. But key to fixing that rise in community harm is to talk about the systemic issues that underlie it, and those include systemic racism and poverty. This is the time for us to have those conversations on all sides.”