COVID Crime and Safety Incarceration Trends May 21, 2020

Law enforcement policy has too often been decided in a data vacuum, in large part due to a lack of sophistication and transparency in how policing data are publicly released.

At the same time, safety-related jail releases of defendants charged with low-level felonies to protect them from the spread of the Coronavirus offer an unprecedented discrete opportunity to test common assumptions about whether releasing people before trial necessarily leads to an uptick in crime.

In the absence of crime data, such early concerns were raised about a possible crime wave related to Coronavirus jail releases, but it turns out that those fears have not been borne out by actual statistics, which we’ve been tracking in Chicago on a weekly basis and reporting on a website.

Instead, the data in Chicago shows a marked drop in overall crime since Coronavirus jail releases began, with total reported incidents down more than 30 percent.

At the same time, since March 15, the Cook County jail population is also down 28 percent, to a level not seen since the early 1980s:

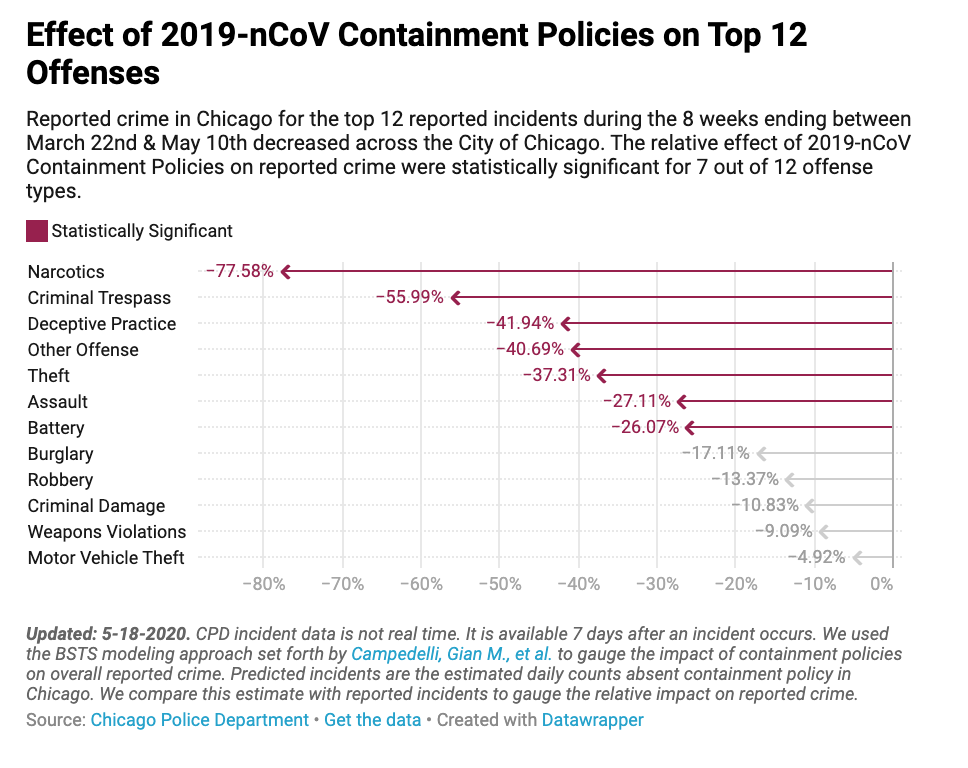

The data also show statistically significant reductions in seven out of 12 of the most frequent offense types, particularly arrests for non-marijuana drug offenses:

The data also show statistically significant reductions in seven out of 12 of the most frequent offense types, particularly arrests for non-marijuana drug offenses:

Chicago and Cook County Justice agencies began containment policies on March 17, when Cook County began a reassessment of bond for primarily non-violent offenders. On March 24th, the Chicago Police Department directed officers to reduce police stops and issue citations in lieu of low-level misdemeanor arrests.

Chicago and Cook County Justice agencies began containment policies on March 17, when Cook County began a reassessment of bond for primarily non-violent offenders. On March 24th, the Chicago Police Department directed officers to reduce police stops and issue citations in lieu of low-level misdemeanor arrests.

Concerns of a crime wave have been raised primarily by law enforcement agencies, although early analysis by the Marshall Project suggested the opposite trend, with reported crime down across the country in major cities. And our own analysis bolsters that.

However, there is also interesting nuance in the data that aligns with underlying structural issues that COVID-19 have illustrated in regards to public health.

The Chicago Tribune found, for example, after filing a public records request, that the police department issued more Coronavirus dispersal orders in Chicago’s West Side neighborhoods, which are markedly more populated by African American people on lower incomes. These neighborhoods also have the highest violent crime rates in the city and the most concentrated areas of economic and social disadvantage.

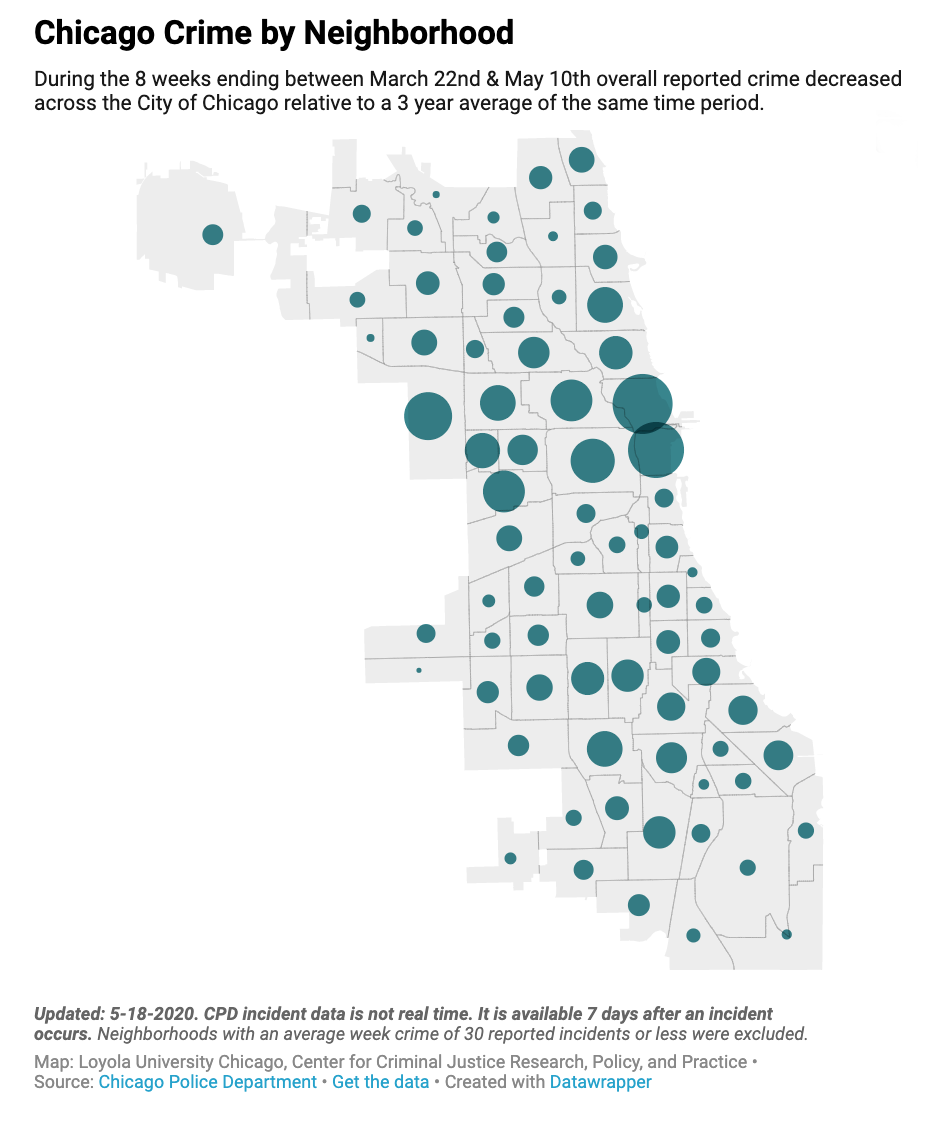

There are structural inequities, including racial inequities, at play in Chicago’s geography. The statistics show a markedly higher reduction in crime in Chicago’s central business district and in many of the more affluent neighborhoods with fewer people of color:

The area where we’ve seen the biggest drop in crime is The Loop—the central business district in downtown Chicago where the businesses, the shopping district, and the financial district are located. And nobody’s there right now—the accountants and attorneys are all working from home, and almost all of the stores are closed to shoppers.

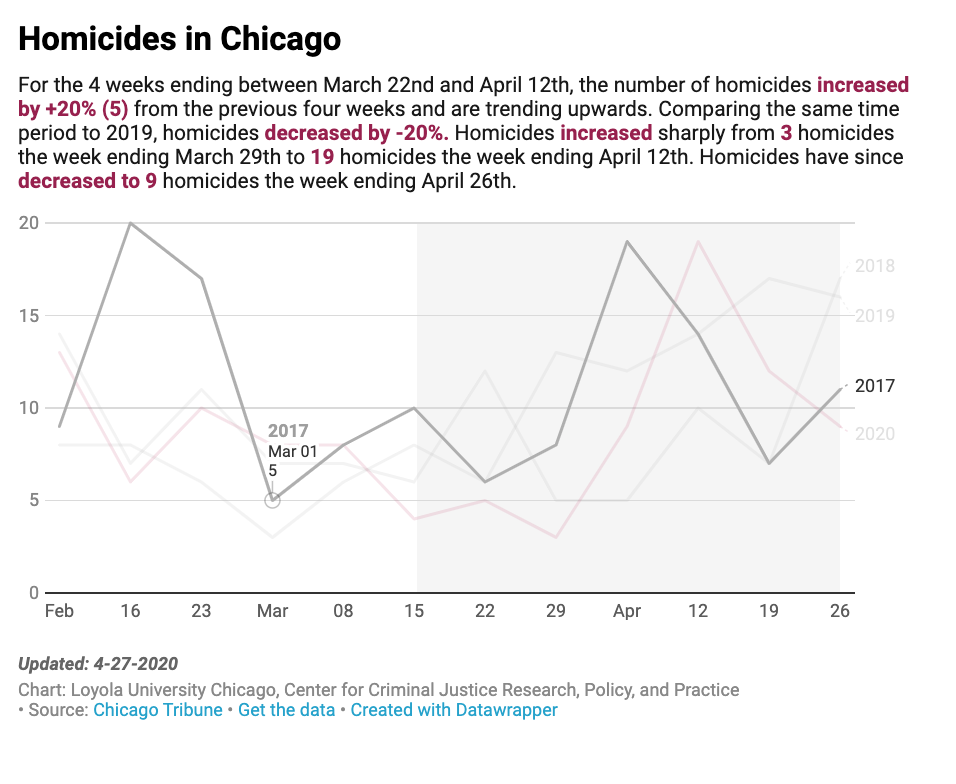

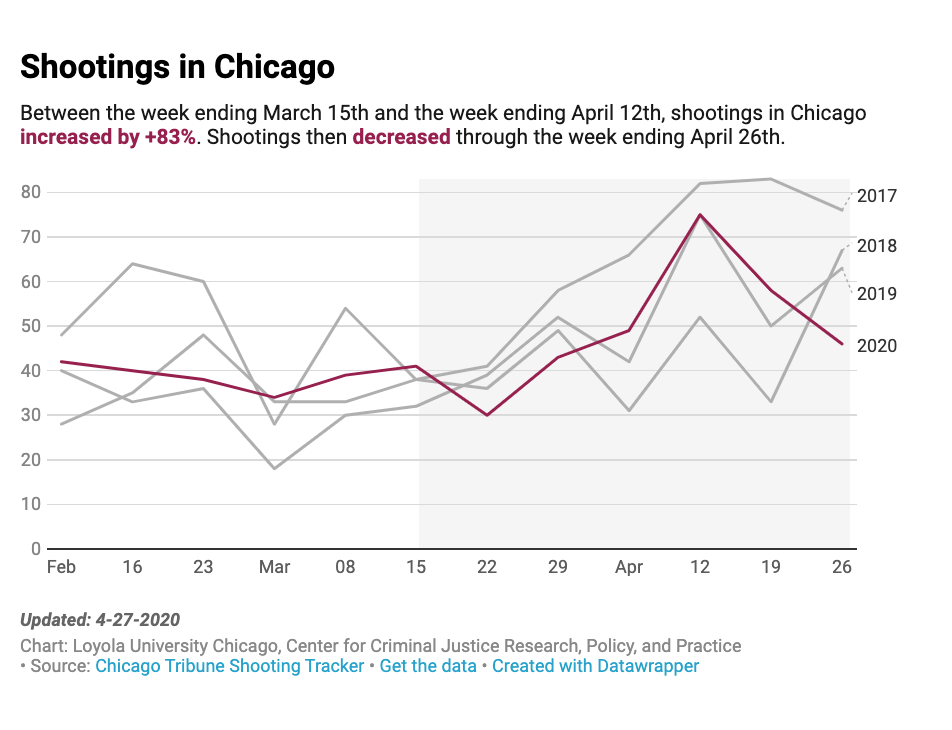

Meanwhile in the areas with higher crime rates, homicides and shootings have been relatively unaffected by the crisis, remaining relatively steady in their week-to-week fluctuations.

The data suggest that we may have reached a statistical baseline, in terms of how much it’s possible to impact crime statistics and the jail population alone.

The data suggest that we may have reached a statistical baseline, in terms of how much it’s possible to impact crime statistics and the jail population alone.

At this point, if we want to further reduce crime or the jail population, then it’s going to need deeper work from a public health perspective to protect the population at greatest risk for shootings and homicides. There are some more intractable issues at play that aren’t interfered with, even by a pandemic.

So far, there’s been limited replication of this kind of statistical analysis, nationally. But we encourage it because it illustrates the powerful impact of police decision making on the system.

By reducing the number of drug arrests in Chicago, for example, police have had a profound impact on the system, and on the jail. There is a systemwide interconnectedness revealed in the numbers.

The question is, once restrictions have been eased, will the Chicago justice system remember what it’s learning from all this?

—Dr. Don Stemen is an Associate Professor and Chairperson in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology and a member of the Graduate Faculty at Loyola University, Chicago.

—Professor David Olson is a Professor in the Criminal Justice and Criminology Department at Loyola University Chicago, where he is also the Graduate Program Director, and is also the Co-Director (with Diane Geraghty, Loyola School of Law) of Loyola’s interdisciplinary Center for Criminal Justice Research, Policy and Practice.