Data Analysis Incarceration Trends Racial and Ethnic Disparities May 11, 2021

A focus of the Safety and Justice Challenge is reducing racial disparities amongst the pretrial jail population. We have made progress on reducing overall jail populations, but racial disparities remain pervasive and need our collective focus. Thus it is important that we collectively understand the difference between equality and equity.

We at the W. Haywood Burns Institute work to achieve racial equity and eliminate racial disparities as a technical assistance provider to the Safety and Justice Challenge. I personally have worked with several sites, including Palm Beach County, Florida, Harris County, Texas, New Orleans and East Baton Rouge in Louisiana, and Buncombe County, North Carolina.

Some of our racial equity work has been featured here on the Safety and Justice Challenge blog over recent months. Here’s a post by Yolanda Fair, a public defender in Buncombe County, for example, describing those efforts. Here’s another post on community engagement in New Orleans by Emily Rhodes and Natalie Sharp, who serve on the Community Advisory Group there.

Together, we have been able to highlight the importance of centering community in the SJC’s work. That means going beyond the traditional ‘community engagement’ efforts.

Community engagement, as it is traditionally attempted, tends to involve seasoned justice reform stakeholders reaching out to community stakeholders to say, “Hey, we just wanted to let you know we are doing this.”

But equity requires something more. It would ensure that those overrepresented in justice systems have access to collaboratives where policy is made. It is asking: “Who’s not here in the room?” It means prioritizing experts who have experienced the justice system and sharing decision-making power with them.

Nationwide, since the extrajudicial police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among many others, we have seen organizations large and small take well-manicured verbal stances in solidarity and calling for change.

I appreciate the words and sentiments put forth in press releases and the like. The vast majority of them call for equality. There’s nothing wrong with the word or concept of equality. But given this nation’s history, equality is not enough.

Here’s why we must push for equity:

It starts with defining the terms. Merriam-Webster defines equality as “the quality or state of being equal.” Think of this as “treat me just the same as anyone else.” Equity, however, is defined as “justice according to natural law or right, specifically: freedom from bias or favoritism.” Think of this as “respond directly to what I need, even if I need more than others to be made whole.”

I’m not saying equality is not our ultimate goal. I am saying that to start treating, say, the Black community “the same as everyone else” at this point in history will not go far enough in terms of achieving true equality.

In racial justice, equality should be the interpersonal standard. On an individual basis, we should all treat each other the same regardless of race. However, on a systemic level—including individuals acting in official capacities within systems—the standard must be equity.

The history of this nation’s relationship with Black lives begins with slavery—complete racial subjugation of people’s every human right and dignity for profit or whim, which we have updated in various ways since. Examples of this updating over the eras include sharecropping, lynching, convict leasing, Jim Crow, and mass incarceration.

However, these are among the more overt ways the Black community has been marginalized. There are many pervasive ways Black people have been discriminated against, and those policies/practices impact the Black community to this day.

For instance, the GI Bill and its benefits were largely denied to Black people despite their qualifications. It was one of the largest wealth creation policies ever, and a primary catalyst to the development of America’s “middle class,” as well as the expansion of the wealth gap between White and Black people. Similarly, redlining was a practice by which banks would refuse to lend to Black people attempting to move into predominantly White neighborhoods in order to promote segregation. It kept Black people and other people of color in economically depressed areas.

We must understand that exclusionary practices like those listed above impact education funding and quality, job access, and upward mobility. The concentration of poverty and chronic disinvestment drives health and quality of life disparities and, ultimately, disparities within the justice system.

We have a history of intentional, strategic, and systemic racialized oppression which has weakened communities of color through no fault of their own. We must address the intentionally oppressive policies which have upheld this country’s racial caste system for far too long.

We can no longer demand communities of color ‘pick themselves up by the bootstraps’ without providing the support which has been systematically denied them. Here is what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had to say about bootstraps: “White America must see that no other ethnic group has been a slave on American soil.”

Equity means responding directly to the needs of each community, group, or individual. It means that while the response may look different depending on the need, the end result or goal would be to put each community on even footing.

Justice from an equity lens means acknowledging that cash bail systems on average ensure that communities of color, which experience significant wealth inequality compared to White people, will stay in jail and suffer life changing consequences because they can’t afford to pay, or might be more willing to take plea deals when they did not commit a crime, among many other examples.

It is only through racial equity—responsiveness to specific needs in communities of color because of the many forms of historic oppression—that we can ever all be equal.

Relishing the dream of equality without understanding the need for equity will doom us to repeat history—even the history we’re living today.

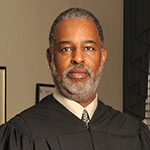

—Christopher James is a member of the Social Justice and Well-being team with the W. Haywood Burns Institute.