Community Engagement Costs Diversion June 22, 2021

America’s over-incarceration problem begins in our local jails. Each year, there are close to 11 million jail admissions in the United States, nearly 18 times the number of yearly admissions to state and federal prisons. In many regions, jail populations have reached crisis levels.

The primary purpose of jails is to detain people who are awaiting court proceedings and are considered a flight risk or public safety threat. Many people admitted to jail cannot afford to post bail and may remain behind bars for weeks, months, or even years awaiting trial or case resolution. Our over-reliance on jails has negative consequences for people who are incarcerated, their families, and communities. Burdens of jail fall disproportionately on communities of color. Black Americans, for example, are jailed at five times the rate of white Americans and comprise a proportion of the jail population that is three times their representation in the general population.

In response, the MacArthur Foundation launched the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) in 2015, and has so far invested $252 million in the effort. Its aim is to help create fairer, more effective justice systems on a large scale.

The goal of the SJC is not just to reduce jail populations, but to do it safely – this has been a pillar of the initiative since its inception. Our previous research has highlighted the substantial reductions made in jail populations across SJC sites since 2015. But our new report provides an initial look at those decarceration strategies through a safety lens. More specifically, it explores how both aggregate crime rates and returns to custody among people released from jail changed after the launch of the SJC and the implementation of decarceration strategies in sites through 2019.

Reducing Jail Populations Without Compromising Public Safety

Our latest analysis runs through 2019 and explores how crime rates changed after the launch of the SJC. It also analyzes returns to custody among people released from jail. We will explore COVID-19’s impact in future briefs.

Our analysis should be viewed as a first step towards assessing decarceration and public safety. Our measures rely on administrative data from criminal justice agencies, and as a result are reflective of the justice system’s responses. Future stages of our work will aim to explore public safety in a much more nuanced manner. For now, our goal is to lay a broad foundation of understanding about the trends we are seeing.

Findings suggest it is possible to craft decarceration strategies without compromising public safety. In fact, our measures of public safety across SJC sites remained about the same before and after reforms were implemented to reduce local jail populations.

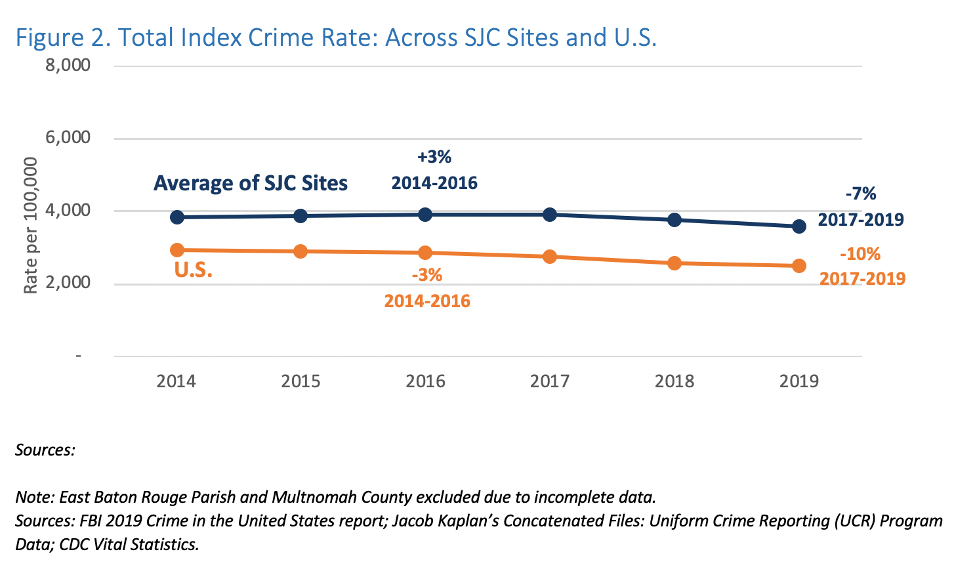

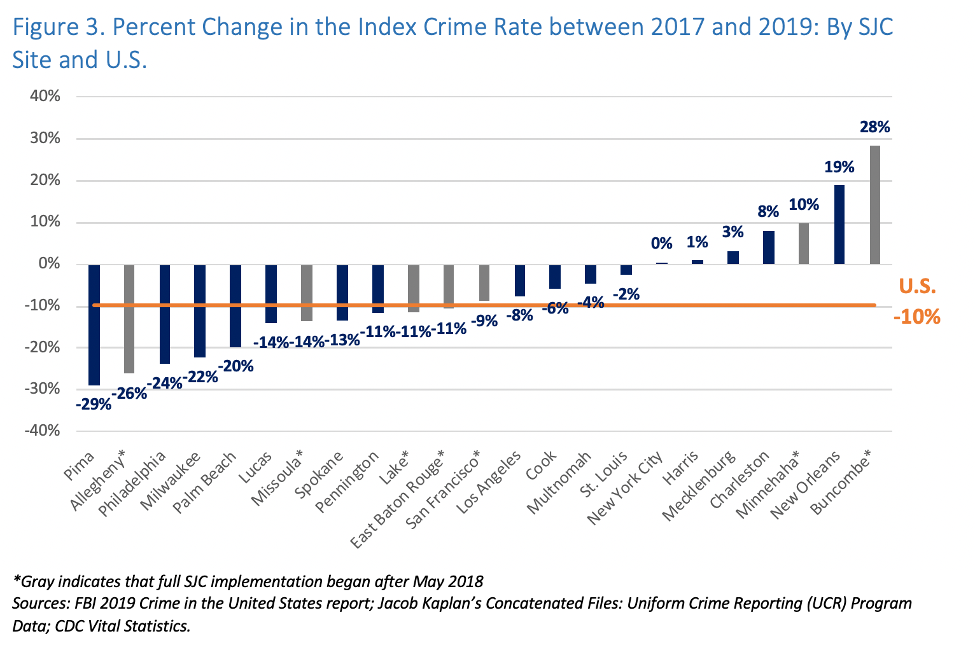

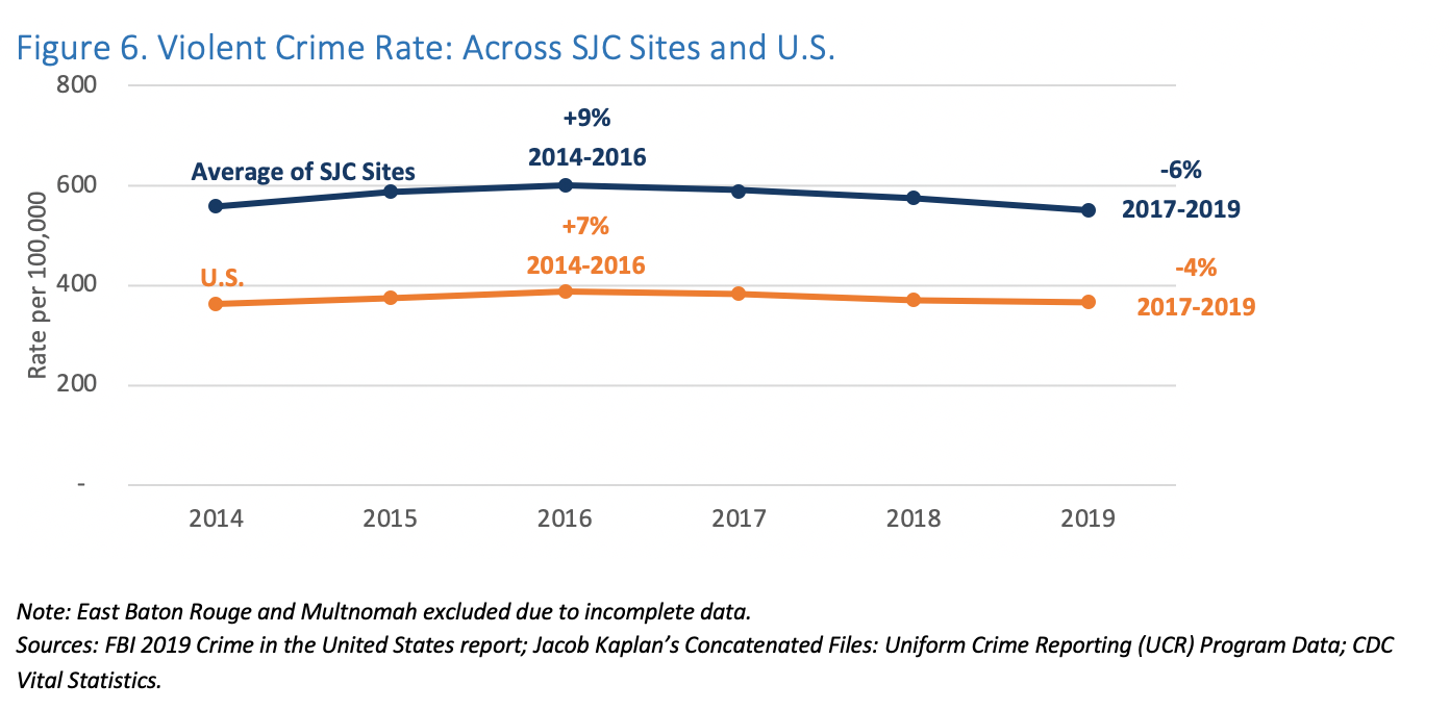

Local Crime Trends Remained Stable or Decreased in Most SJC Sites

During the first few years of SJC implementation, 11 sites experienced a reduction in index crimes greater than 10 percent. The majority (19) either experienced some decrease or remained the same.

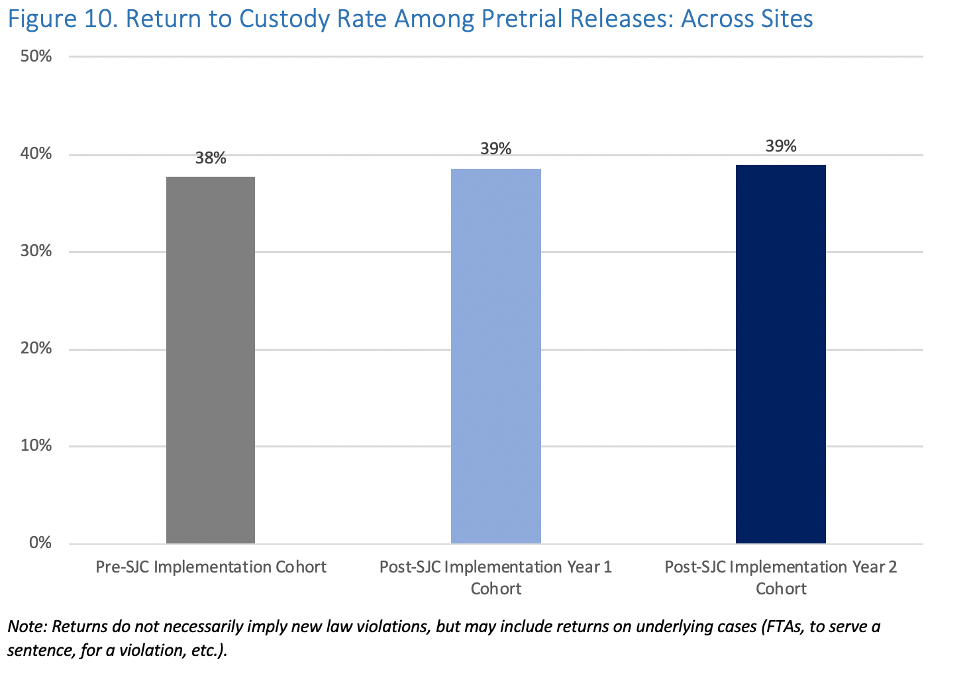

The Rate of Returning to Jail Custody Was About the Same

Among individuals released from jail pretrial, return to custody rates for felonies, misdemeanors, property crimes, and violent crimes within a year remained about the same.

Being returned to custody on a violent charge was rare before and after SJC implementation; being returned on a homicide was very rare. Most individuals who returned to custody within a year did not return on a more serious charge.

Regardless of the specific charge type, return to custody rates among those released pretrial did not change after the implementation of decarceration reforms began.

Prior to the implementation of SJC jail population reduction strategies, 38 percent of people released on pretrial status were returned to custody within 12 months of their release. (Note that our return to custody measure includes returns for reasons other than a new criminal charge—future work will focus more narrowly on returns that involve new charges.) This remained true in the years following SJC implementation – of those released pretrial in the second year of the SJC implementation, 39 percent returned to custody within a year. The vast majority of sites did not experience an increase in the return to custody rate after SJC implementation began.

Conclusions

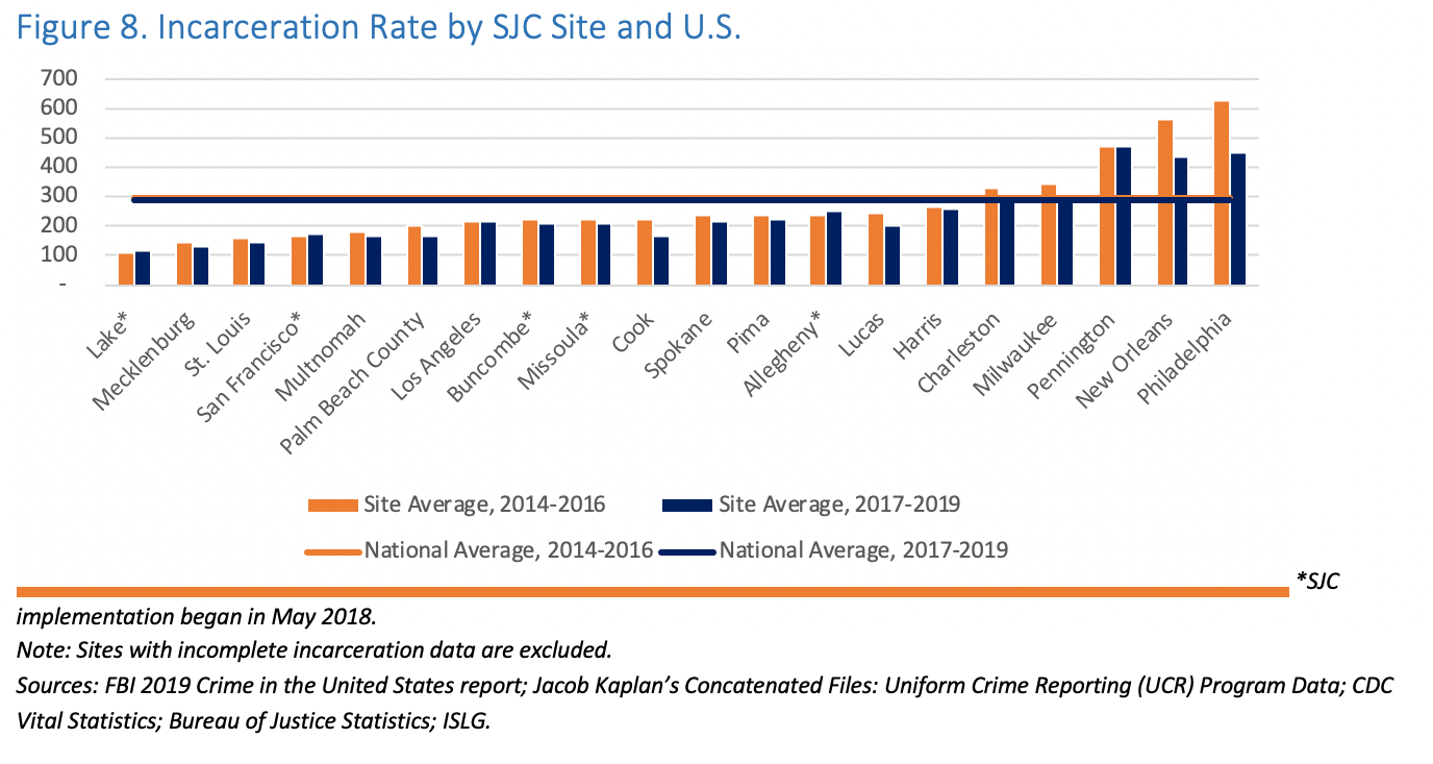

The findings of this analysis suggest that decarceration efforts in SJC sites did not endanger public safety as measured by crime rates and returns to custody. As incarceration rates declined during the SJC, crime and violent crime rates also dropped or remained the same in most sites, mirroring national crime rate trends. When examining individuals who were returned to jail custody within a year of release, the rates of return were about the same before and after the SJC – suggesting that decarceration efforts, especially among the pretrial population, do not lead to a higher rate of returns. Importantly, returns to custody for violent crime charges and homicide charges were rare before and after the SJC. Of course, our measures are not inclusive of all definitions of public safety. Future work will examine the public safety implications of the SJC more comprehensively.

More on the Data

SJC sites share jail population data once a month with the Institute for State and Local Governance (ISLG) at the City University of New York (CUNY). A subset of sites submit detailed case-level jail data to ISLG once a year. We sourced crime data from the FBI 2019 Crime in the United States report.