Data Analysis Human Toll of Jail Incarceration Trends September 23, 2021

The FBI’s annual crime stats report is due out on Monday. In more than a quarter century of correctional planning and research, I’ve seen a variety of reactions to these numbers—including plenty of fearmongering and distortion. But there has never been a better time for us to keep a clear head and take an objective look.

What We Already Know

There are a few things we already know even before the FBI releases the data. Overall, serious crimes went down, not up, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet polling showed the American public believed there was more crime in the United States than there was a year before. It isn’t true.

One of the reasons crime dropped in 2020 was the COVID-19 lockdown itself, which restricted social interactions that can lead to criminal activity. But the pandemic also gave many jurisdictions the opportunity to implement needed law enforcement court processing reforms that have resulted in fewer arrests for low-level crimes, fewer jail bookings, and reduced jail and prison populations. All of this occurred without an increase in overall crime rates.

It is true, however, that in many places in the country homicide and shootings increased in 2020. But most other forms of violent crime either have not risen as steeply or have dropped during the same period. Moreover, there is growing evidence that in cities where the homicide rate turned markedly up, the increase is slowing. These are the findings presented in a report by the Council on Criminal Justice, a non-partisan organization that works to advance understanding of the criminal justice policy choices facing the nation, which has been studying the effects of the pandemic on the justice system.

Putting New Data in Historical Perspective

It’s also important to keep a sense of historic perspective looking at the numbers.

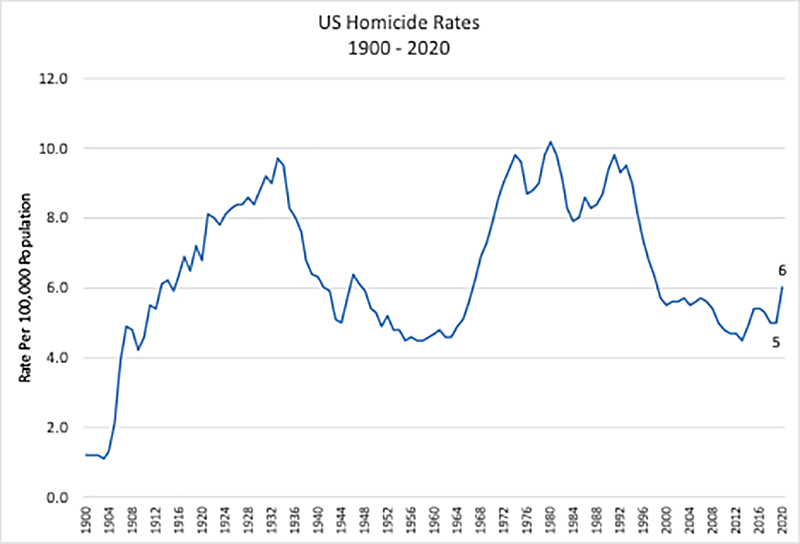

Crime rates have dropped by more than half since 1995. Homicides, the rarest of all crimes, have also declined. But as the chart below shows, homicide rates since 1900 have shown a lot of fluctuation, ranging as high as 12 per 100,000. And the “jump” in homicides from 2019 to 2020 is likely to be from five per 100,000 people to about six per 100,000. That means there was a one-one-hundredth percent change in the homicide rate, which is statistically insignificant and not at all out of line with historic fluctuations.

There have been similar and even higher changes in the homicide rate, for no apparent reason. One must concede that a large portion of changes (up and down) in the homicide rate is random.

That’s not to say we should not be concerned about any increase, or for that matter, any one homicide. But equating a rise in homicides with an increase in crime rates when crime rates have declined is misleading the public.

The Role of Criminal Justice Reforms in Addressing Homicides

Homicides are concerning especially for those people who live in areas where they occur most frequently. But the increase calls for a thoughtful response, including focused law enforcement resources and community-based anti-violence programs. Intervening earlier in the lives of people who commit homicides is a far more positive and effective approach to reducing homicide rates.

Predictably, commentators and editorial boards will be eager to pin the blame for the rise in homicides on a “lax” criminal justice system, “progressive” prosecutors, bail reform, and declining jail and prison populations. They’ll tell you police have lost their motivation to do their jobs because of calls for accountability over violence and racial justice. But that’s not what is likely to be reflected in the numbers.

The solution to homicides is to spend money more smartly on targeted approaches. Not prey on people’s misplaced fears to justify indiscriminate spending on ineffective public policy.