Bail Pretrial November 19, 2020

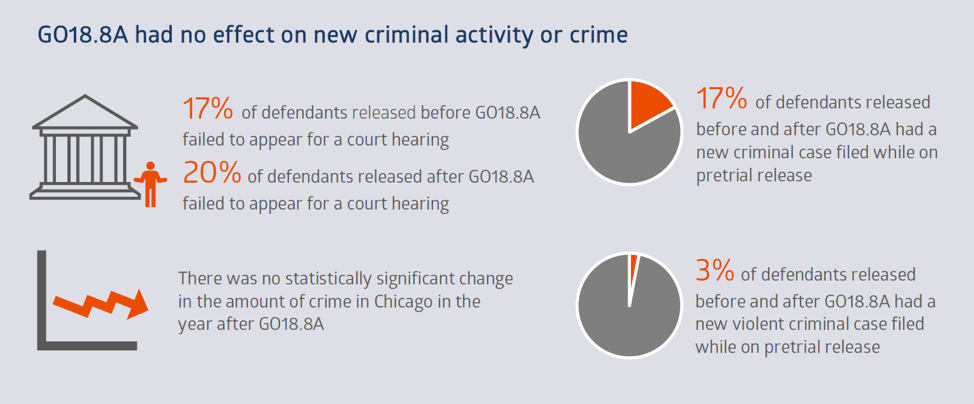

New academic analysis shows Chicago area bail reform efforts since 2017 have had no impact on new criminal activity or new violent criminal activity of those defendants released pretrial.

Overall crimes rates in Chicago, including violent crime rates, were not any higher than expected after the implementation of the effort. The analysis echoes that performed in other areas where similar bail reform efforts have been undertaken such as New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia.

You can read the full report here.

Everyone wants safe communities. But our research suggests that releasing people on their own recognizance does not make communities less safe. And taking money away from people to secure their release does not make communities safer. Monetary bail, however, does impose a burden on those individuals and their families who are least able to afford it.

Like bail reform efforts in other cities, Chicago’s initiative demonstrates that it is possible to decrease the use of monetary bail and decrease pretrial detention – and lessen the financial, physical, and psychological harms that come with pretrial detention – without affecting criminal activity or crime rates.

In Chicago, the effort began on September 17, 2017, when the Chief Judge of the Circuit Court of Cook County issued General Order 18.8A (GO18.8A) to reform felony bail practices in Cook County.

GO18.8A established a decision-making process for felony bond court judges. Under the order, bond court judges were to first determine whether a defendant should be released pretrial and, if not, hold the defendant in jail. If the defendant could be released, GO18.8A created a presumption of release without monetary bail; however, if monetary bail was necessary, the order stated that bail should be set at an amount affordable for the defendant. In the end, GO18.8A established a presumption of release without monetary bail for the large majority of felony defendants in Cook County and encouraged the use of lower bail amounts for those required to post monetary bail.

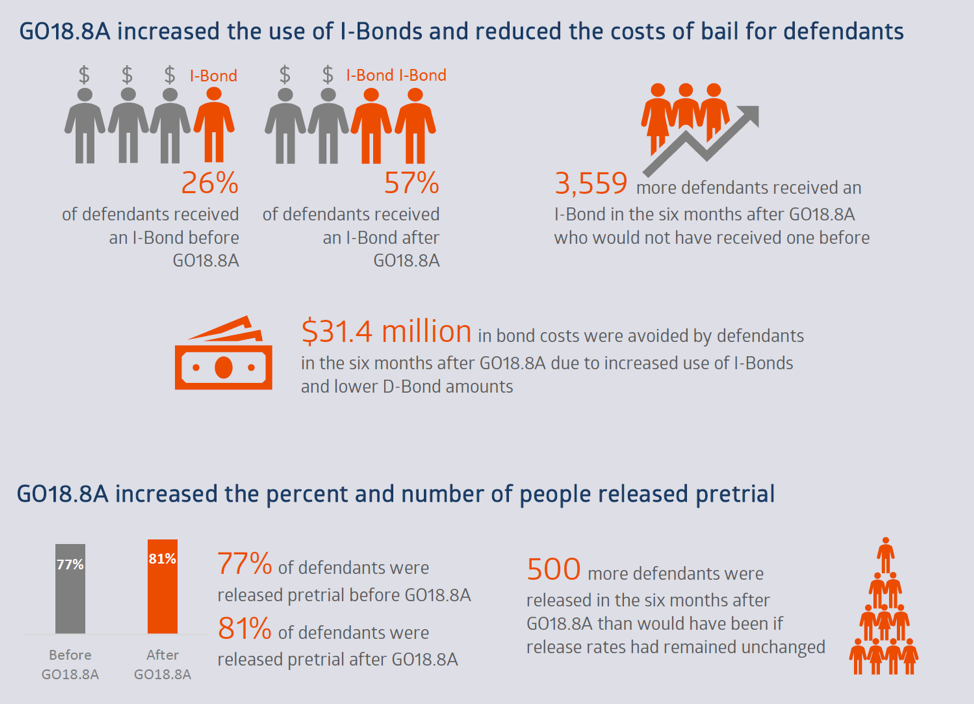

After GO18.8A, there was a significant increase in the use of I-Bonds, or individual recognizance bonds for which defendants are released without having to post monetary bail.

The impact of this shift was dramatic: 3,559 additional people received an I-Bond in the six months after bail reform began. The real impact of this change was that none of these defendants had to post monetary bail to be released pretrial, saving these defendants and their families $13.6 million in avoided bond costs.

D-Bond amounts, where a defendant pays 10% of the bail amount to secure release from jail–were also lower after bail reform. Before the effort began, the average was $9,316 to secure release, compared to $3,824 afterwards.

Combined with increased I-Bond usage, our analysis showed that Chicago saved defendants and their families more than $31.4 million in the six months after the initiative was introduced. That means bail reform in Chicago allowed defendants and their families to have $31.4 million available to be used for rent, food, and medical care while their cases were being resolved.

Likewise, the initiative did this without affecting new criminal activity of those released or increasing crime.

Bail reform efforts across the United States have accelerated in recent years, driven by concerns about the overuse of monetary bail, the potentially disparate impact of pretrial detention on poor and minority defendants, and the effects of bail decisions on local jail populations.

Proponents of bail reform advocate for reducing or eliminating the use of monetary bail, arguing that many defendants are held in jail pretrial solely because they cannot afford to post bail. Opponents counter that reducing the use of monetary bail or increasing the number of people released pretrial could result in more defendants failing to appear for court.

A debate has also played out in the media regarding the link between GO18.8A and possible diminished safety, but until our analysis, a rigorous, objective, external assessment has been lacking.

Ultimately, we found that money should not be the mechanism by which the court determines which people to hold and which people to release. Opponents of bail reform may continue to argue that reducing the use of monetary bail and increasing the number of people released pretrial will result in more defendants committing more crimes while on pretrial release. But that is not what happened following bail reform in Cook County, consistent with experiences following bail reform in New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia.

—Dr. Don Stemen is an Associate Professor and Chairperson in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology.

—Professor David Olson is a Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Loyola University Chicago and is also the Co-Director (with Diane Geraghty, Loyola School of Law) of Loyola’s interdisciplinary Center for Criminal Justice Research, Policy, and Practice.