A new R Street Institute report supported by the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge explores the successful implementation of pre-arrest diversion strategies in three conservative communities. Such strategies respond to challenges facing law enforcement agencies across the country including staffing shortages, negative public perception, overpopulation in jails, increases in violent crime, and court backlogs.

While criminal justice reform can be a politically charged term, we found that several conservative jurisdictions champion pre-arrest diversion as a way to support law enforcement and to remain fiscally disciplined. These jurisdictions have prioritized police time and resources, enabling law enforcement to deal with serious crimes while simultaneously rebuilding community relationships. They have also effectively diverted low-level offenders while balancing individual rights and public safety. The paper spotlights three jurisdictions that employ at least one diversion strategy, and in so doing, reveals how the traditionally conservative values of public safety, fiscal responsibility, and limited government interference are at the core of such programs. The paper also explores how to overcome challenges around starting diversion programs.

Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD)— Cheyenne, Wyoming

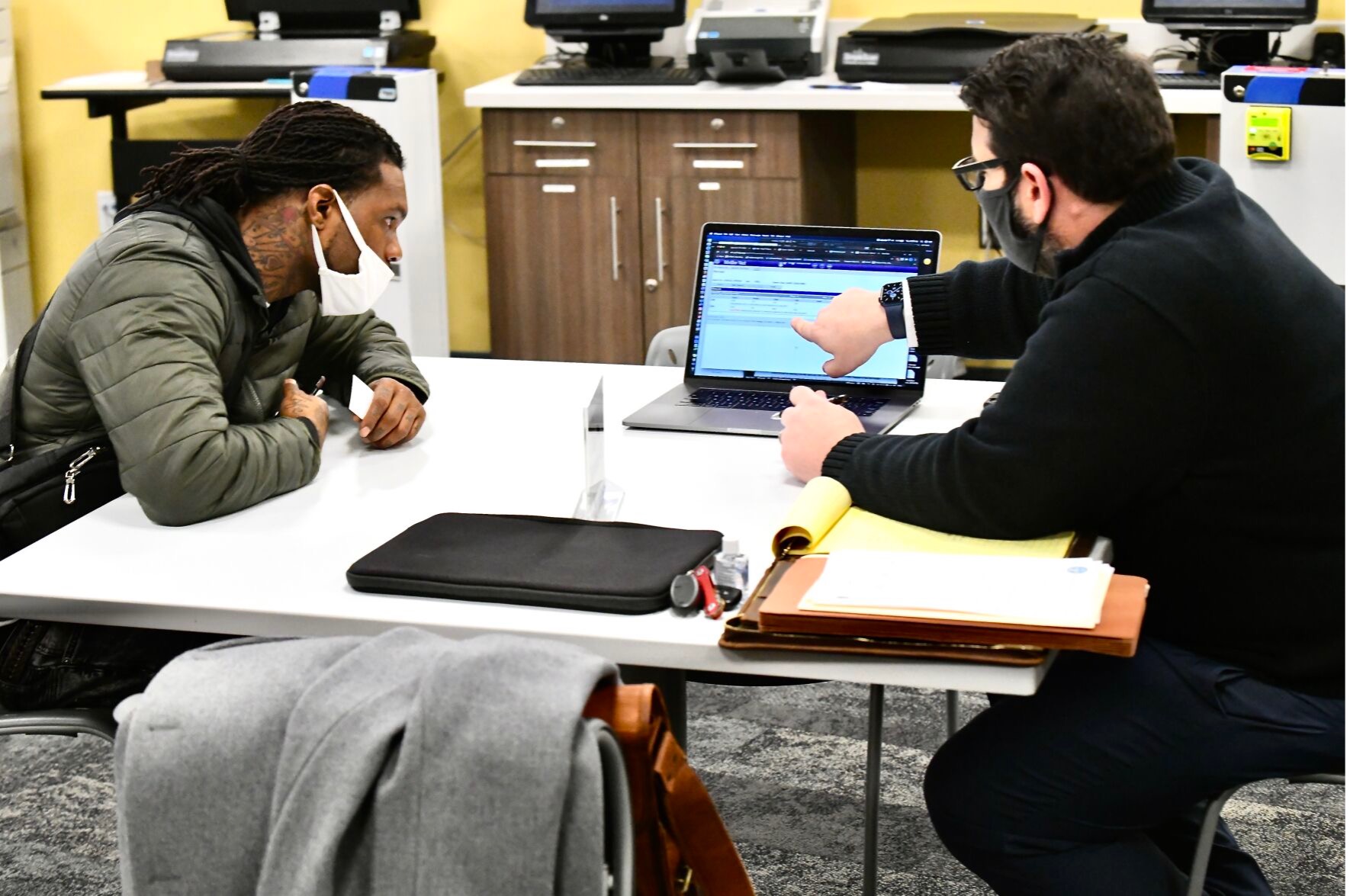

Police-initiated diversion gives officers the opportunity to refer someone to intensive case management outside the criminal justice system rather than cite or arrest the individual for a crime.

Laramie County, Wyo., where Cheyenne is located, has been particularly successful in implementing Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD). The community explored this option after finding that prosecuting and jailing individuals with behavioral health needs was ineffective in improving public safety. Officials and professionals merely saw a “revolving door” of the same individuals. Further, Cheyenne had seen a steady increase of mental health calls, violent crimes, and overdose related deaths; they needed to try something different.

When the program first began, some officers were hesitant to refer individuals to LEAD. In fact, one lieutenant at the Cheyenne Police Department feared LEAD, “wasn’t holding people accountable and just allow[ed] people to screw up with no consequence.” But many officers gradually saw the positive results. The lieutenant who initially was a skeptic eventually became “all in.” Officers realized that even if individuals were being arrested, they returned to the streets upon release with no support or services in place to help them change behaviors, with many returning to drug use or other destructive activities. LEAD has been a positive step for these individuals. In fact, officers tracked how many contacts they were having with people who were frequently arrested and found after a LEAD referral, officers had not talked to many of these individuals in months. One individual said the LEAD program saved his family member’s life.

Co-responder Model— El Paso County, Colorado

Though police officers generally do not have the training to handle mental health crises, many communities rely upon police to handle such issues. In an effort to support law enforcement in these situations, many communities have implemented co-responder programs. In a co-responder model, a behavioral health clinician (and in some models, emergency medical personnel) accompany law enforcement on patrol.

The sheriff’s office in El Paso County, Co. formed their own co-responder program, the Behavioral Health Connect Unit (BHCON), in 2017 after realizing they needed to reduce jail intake rates. When researching how to reduce the jail population, they realized that a high number of incarcerated individuals suffered from mental health issues. The BHCON team now responds to mental health crisis calls as well as low-level crimes in which it is clear that the individual’s mental health crisis—rather than criminal intent—is the cause for the criminal act.

This immediate response to someone in crisis has resulted in a reduction of expensive arrests and jail admissions as well as a reduction in mandatory psychiatric holds (often referred to as a “72-hour hold”) that are often done in hospitals. In 2021, BHCON responded to 1,154 calls for service. From those calls, BHCON diverted 99 percent from jail and 85 percent from the emergency department. At a time when hospitals are having to divert patients (due largely to COVID-19), saving hospital space is essential. BHCON has also relieved law enforcement of having to rely on the jail as a de facto mental health facility when an individual does not meet the threshold for a mandatory psychiatric hold.

Community Responders— St. Petersburg, Florida

Too often, law enforcement is responding to noncriminal calls where their presence is not necessary. Community Responders (or Civilian Response) takes the co-responder model and removes the police officer entirely. That is, community responders divert individuals from the criminal justice system by having trained, non-law enforcement professionals respond to certain calls for service that do not require a gun and a badge.

This model is the most effective at reserving police resources for the most dangerous crimes while also lowering the potential of escalating a situation by removing the presence of law enforcement. Instead, dispatch alerts community responders who have backgrounds and specific training to help in situations where behavioral health and/or social concerns are the prominent issue.

In 2019, St. Petersburg’s police department partnered with a local nonprofit to form Community Assistance and Life Liaison (CALL). Under the CALL model, clinical staff and community navigators respond to calls such as panhandling, truancy, welfare checks, mental health holds, and disputes between neighbors. When initiating the program, the St. Petersburg Police Department believed such a program could respond to approximately 12,700 calls, diverting individuals from the criminal justice system.

Overcoming Challenges to Diversion

While law enforcement agencies and local elected officials seem to be open to the idea of diversion, many jurisdictions face hurdles when it comes to implementation. Even with proven success, available funding, and law enforcement buy-in, concerns of logistics, safety, and cost can create hurdles. The report focuses on ways these communities have overcome such challenges and shows it is time for other communities, of any political leaning, to support law enforcement in shutting down the inefficient revolving door of the criminal justice system. Ultimately, these pre-arrest diversion programs can and should be implemented to increase public safety, protect personal rights, and save taxpayer dollars.