Featured Jurisdictions Interagency Collaboration Jail Populations April 14, 2016

Counties and cities nationwide are taking steps to reduce the number of individuals held in their jails. Inmate populations have grown four-fold since 1970, and there is a growing awareness that many of those held pretrial present little public safety risk and are likely to appear for their court dates. There are many factors that have driven the growth of jail populations—from rising bail amounts to changes in law enforcement practices. When crime rates were higher 30 years ago, there were 51 admissions into jail for every 100 arrests. By 2012, that number had climbed to 95 per 100. And while jail administrators are tasked with responsibility for the constitutional care and custody of a growing population—too often with a budget that does not also rise—there is generally little they can do to reduce the number of people held in their jail, which is driven by the decisions of police, prosecutors, and judges.

In the past, the answer to the problem of increasing jail populations was to expand jail capacity. But today, many are instead asking “what size should the jail be?” Answering this question is challenging, particularly because it is difficult to get basic data on how the jail population and local incarceration rate has changed over time, a first step in understanding what has driven jail growth, and what might change it.

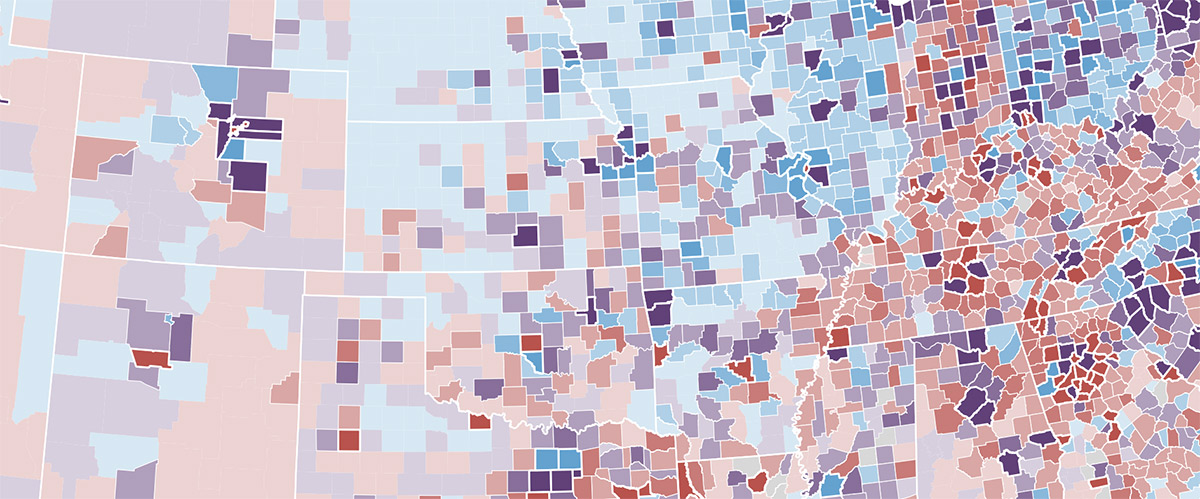

To address this data gap, the Vera Institute of Justice developed the Incarceration Trends data tool (available for free at trends.vera.org), which aggregates the jail population and admissions data that corrections officials have submitted to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics since 1970. This new tool allows anyone to examine county-level trends in the jail incarceration rate, and compare these trends to state and national averages and other specific counties.

A review of this data tells us that there is wide variation in incarceration rates among similar jurisdictions: while in the 1970s, county incarceration rates rarely exceeded 300 per 100,000 residents age 15–64, today the county rate averages more than 300 per 100,000 nationally, and is greater than 1,000 per 100,000 in more than 100 counties. And each county’s jail problem is different. Too many people in the jail is one issue, but not the only one: who those people are is another, for example, as is how long people stay in the jail.

The Incarceration Trends data tool provides a means to explore the answers to five questions that can inform a data-driven conversation on how the county uses its jail.

1. How does the county’s jail incarceration rate today compare to the state and national average? If the county jail incarceration rate exceeds these averages, it suggests there may be an opportunity to reduce the jail population to at least bring it in line with current norms. But it is important to keep in mind that the national average itself has grown substantially and is a high benchmark from a historical perspective. It doesn’t necessarily tell you what the rate for a particular county should be.

2. How does the county’s jail incarceration rate today compare to its historical trend? After four decades of growth, it is sometimes easy to forget that jails were not always the size they are today. If a county’s incarceration rate is now substantially higher than it once was, why is that? Is it justified by the county’s public safety needs? Are defendants incarcerated now who wouldn’t have been in prior years? If so, why? Pretrial detention for defendants accused of low-level offenses has risen dramatically over the past 30 years and many jurisdictions are questioning the value of this practice (and its cost).

3. What factors have driven jail population growth? The size of the jail population is driven by the number of admissions and the average length of stay. Which factors have driven jail growth? A growth in admissions can reflect, for example, changes in law enforcement arrest and booking practices, the prosecutor’s approach to charging, or the jurisdiction’s policy and practice around pretrial release. Growth in length of stay suggests challenges in processing cases; a function, perhaps, of rising numbers but also systemic inefficiencies.

4. Has the incarceration rate for women grown disproportionately? The number of women in jail nationwide has increased by 14 times since 1970—from 8,000 to 110,000—compared to a 4-fold increase for men. Women now comprise 16 percent of all incarcerated individuals and are often held in jail for low-level charges. Can you document a rising number of women in your jail? If so, what might be driving it?

5. Are racial and ethnic minority groups disproportionately represented in the jail, and if so, has that disproportionality grown over time? The overuse of the jail is not only measured by the size of the jail population, but also how certain demographic groups are overrepresented. These disparities can be hard to discuss but shed necessary light on policies and practices within the local justice system that may have a disparate impact on different groups.

The wide variation in the use of jail among similar counties demonstrates that the number of people behind bars—and their demographic disparities—is largely the result of policy and practice choices. And while corrections officials cannot decide who lands in the jail, the public looks to jail administrators for leadership when it comes to thinking about the county’s jail needs. With this information we hope that jail administrators nationwide can lead a conversation with their justice-system colleagues on the use of the jail.

This article was originally published in the American Jail Association 2016 Produces & Services Resource Guide.