Located in eastern Missouri just west of the City of St. Louis, St. Louis County has a population of more than one million residents, making it the most populous county in the state. The 21st Judicial Circuit, located in the county, is also the largest and busiest in the state, handling some 88,000 cases every year. With the support of the MacArthur Foundation, St. Louis County is implementing several strategies to reduce its jail population safely, including expanding its pretrial release program, expediting cases for probation violations, expanding the use of treatment courts and deploying an interdepartmental jail population review team.

What were some of the issues occurring in the St. Louis County justice system that prompted you to apply for the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC)?

St. Louis County and the University of Missouri – St. Louis applied for the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) in 2015, shortly after the events in Ferguson, Mo. As for many jurisdictions across the nation, Ferguson was a turning point in the conversation about justice reform in our community, adding greater urgency to ongoing work by stakeholders in the County committed to improving the justice system.

At the time, the St. Louis County Jail was at capacity. We wanted to reduce the jail population and improve case processing in the courts and we felt that the SJC would offer us a framework and resources for reform. The county also wanted to address equity and racial and ethnic disparities in the justice system. There are embedded systemic problems of poverty, housing, substance use, unemployment and education access that have exacerbated racial and ethnic disparities in our jail population. We felt that the SJC would provide an opportunity for the community to address these problems, as well as, be a medium to bring criminal justice stakeholders, service providers and the larger community together to collaborate on finding solutions.

What are the main drivers of your jail population?

At the beginning of the SJC, we conducted a detailed analysis of the jail population to determine the drivers. This was one of the first times that the county had an opportunity to systematically review data on the jail and the justice system as a whole. The pretrial population is one of the major population drivers. We found that many of these individuals were staying in jail for an inordinate amount of time (more than 100 days) due to their inability to post bail. This issue reflects the systemic factors mentioned before, such as poverty, unemployment, homelessness and substance use. The sheer volume of cases filed in St. Louis County presents a challenge to efficient and timely case processing. Through our analysis, we also found that a large portion of the jail population consisted of individuals who had returned to jail due to a probation violation.

There had never been an analysis of our case processing system until the SJC. That analysis suggested the need for greater collaboration and coordination among leadership and staff at the jail, courts and probation, in order to improve efficiency in processing individuals being held pretrial and identify non-violent individuals who can be released without impacting the community’s safety.

Can you give an overview of the programs, policies and practices that St. Louis County has implemented as part of your SJC work?

Our first strategy is to enhance our pretrial release program. Although a pretrial release program existed before we started the Challenge in 2015, it has been expanded to include more individuals in our jail. We are working with local social service providers to provide mental health and substance use treatment, education and other social services to some of those individuals who have been released. As a result, not only are more individuals being released, they are now better served in the community. We are in the process of adopting the Laura and John Arnold Foundation’s Public Safety Assessment (PSA) tool and plan to start using it in fall 2019. We hope it will continue to provide relevant criteria on which to increase the number of individuals released pretrial and reduce racial and ethnic disparities.

The second strategy is to expedite cases for individuals who have returned to jail for violating the terms of their probation. These individuals make up a significant percentage of our jail population, and they generally have longer lengths of stay. This primarily had been due to the lack of coordination between the probation department and the jail. Now, however, probation and parole officers are working in the jail to screen people being held for parole violations and fast track them back to probation, or to the Missouri Department of Corrections if their probation has been revoked. The goal is to reduce the average length of stay in jail for these individuals.

Our third strategy is the convening of a Jail Population Review Team to identify best practices for effective, safe and just case processing while maintaining community safety. The team meets weekly to review cases of incarcerated individuals charged with less serious, non-violent felonies, and identify those who can be safely released from jail, or whose cases can be expedited in the courts. The team considers barriers to release, alternatives to incarceration, justifications for alternatives to incarceration and recommendations for next steps. The team’s recommendations are then forwarded to prosecutors, public defenders and judges handling the cases. The team includes: the Presiding Judge of St. Louis County; circuit judges who handle criminal cases; county justice department employees; including the staff psychologist; law enforcement officers; public defenders; prosecutors; a member of the criminal bar; a mental health court representative; community service providers and community advocates. This strategy has led to a significant improvement in collaboration and efficiency in the St. Louis County criminal justice system. By engaging stakeholders from different agencies in asking questions and collaborative problem-solving, we are not only saving time, but building trust and strong relationships throughout the system.

Our fourth strategy is increasing the use of treatment courts as an alternative to incarceration. St. Louis County currently has mental health, veteran’s, drug and DWI courts. When individuals in jail meet certain criteria, they are eligible to participate in treatment court programs as an alternative to incarceration. The 21st Circuit recently expanded its mental health court and hired a mental health coordinator to connect individuals in jail who have mental health issues to services in the community. The court is in the process of establishing a mental health resource center, funded by a three-year grant from the Sidney R. Baer Foundation.

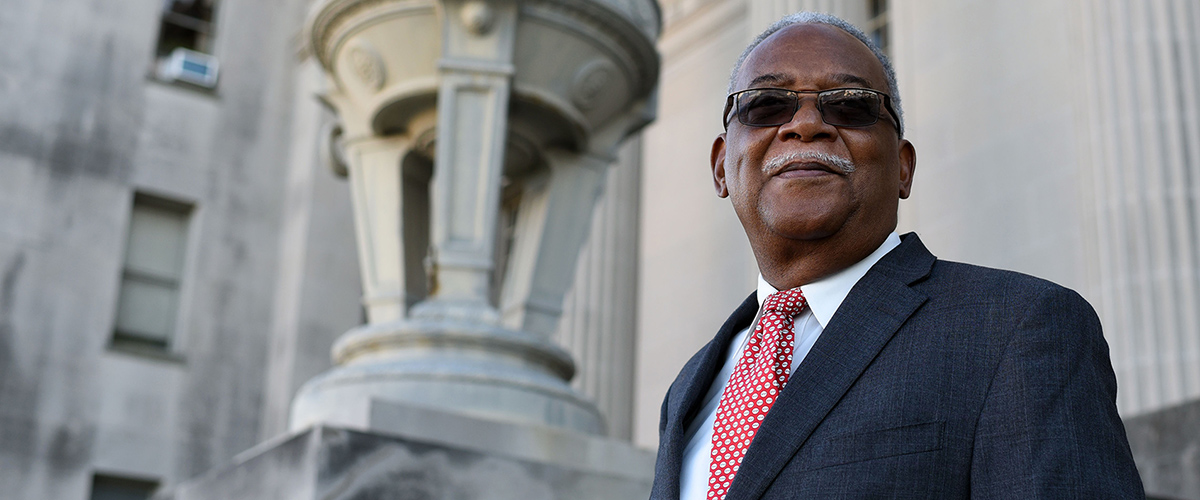

The Veteran’s Treatment Court was founded by former Presiding Judge Douglas R. Beach in 2015. It provides mental health and substance use treatment, housing assistance and workforce training for veterans of all ages – including those who served in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. As a Marine, Judge Beach takes a lot of pride in helping those whose courage and sacrifice have helped preserve our freedom and liberty. Our DWI and Drug Treatment Court programs are offered as alternatives for individuals with substance use issues. Participants in these programs – which can last up to two years – may be required to perform community service, attend individual therapy and/or group therapy and make regular check-ins with the court. These courts have periodic graduations for individuals who successfully complete their treatment programs. These programs have sharply reduced recidivism rates, helped preserve families and helped individuals live healthier, more productive lives in the community.

Who is involved in your Safety and Justice Challenge efforts? Was everyone on board from the beginning or did you have to convince people to sign on?

We have had strong involvement from leaders within the justice system from the beginning. Individuals from the St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney’s office, the criminal bar, the county justice department, probation and parole offices, judges in the 21st Circuit Court and law enforcement officers are heavily involved in SJC efforts. The collaboration has led to better communication and greater trust across the board. By looking at the justice-involved population from multiple perspectives, we are better able to identify areas where we can make real progress. Although there has been some turnover in St. Louis County government (including the appointment of a new County Executive and the election of a new Prosecuting Attorney), those involved in the SJC have maintained a strong commitment to the process and to reform. The reform agenda of the Prosecuting Attorney, Wesley Bell, has been vital to the expansion of the use of treatment courts as an alternative to incarceration.

The events that took place in Ferguson, Mo., in 2015 made justice stakeholders in the county want to actively engage in systems reform. This momentum has been constant through the entire time of the Challenge and has helped us achieve our goals. There is strong bipartisan support among county leaders and residents for reducing mass incarceration and addressing racial disparities. Within the past few years, there has been an evolving conversation about what can we do to keep the community safe while finding effective alternatives for individuals involved in the criminal justice system. The MacArthur Foundation and the technical assistance providers for the SJC have provided a forum for this work and helped bring people from across the system together on a regular basis to actively collaborate on reform. Everyone involved has been excited about the potential of the Challenge’s impact on the jail population and how people working in the system view and work with one another.

How is St. Louis County using data and sharing information among agencies and systems to help with your Safety and Justice Challenge efforts?

Data has been an integral part of our SJC efforts from the beginning. During the planning phase, we used data to look at different aspects of the jail population, specifically how long individuals spend in jail on average and identifying racial and ethnic disparities. Data was key to bringing people on board and to showing where we should focus our SJC strategies. We are also using data to evaluate the impact of our SJC programs and strategies. For example, we are using data to evaluate the outcomes of our pretrial release program, tracking whether individuals are returning to court and identifying gaps in services. We use this data to inform our day-to-day decisions.

Data also plays a major part in the deliberations of our Jail Population Review Team. We analyze jail population data on a weekly basis. This data provides our team benchmarks and goals to strive toward. Data is also integral for our goal to reduce racial and ethnic disparities within St. Louis County’s justice system. The data shows that, like many jurisdictions, racial and ethnic disparities exist at all levels of our system. This is particularly true of the average length of stay in jail. Many persons of color do not have money for bail or legal representation at their first court appearance, which can result in a reduced likelihood for pretrial release and therefore longer jail stays. This data can help us identify obstructions in the case processing system and inform our strategies to reduce racial and ethnic disparities moving forward.

What outcomes have you seen so far and what do you hope to see long term?

We have already seen positive outcomes from our SJC strategies. Our original goal was to reduce the jail population by 15-19 percent. We have already surpassed our goal and have reduced the population by 24.4 percent. We have also reduced the average length of stay for individuals in jail due to probation violations from 99 days to 10-15 days on average. The share of our jail population that is incarcerated due to probation technical violations has decreased from 29 percent to 13 percent. We have seen a decline in racial and ethnic disparities for the probation violation group as well. We have reduced the population of individuals with non-violent felony offenses in jail by half (from 35.3 percent to 15.3 percent of the total jail population) because of the expansion of our pretrial release program and formation of the Population Review Team. These reductions save taxpayers money and return people to their families and jobs while awaiting trial.

Our biggest goals moving forward are to continue to right-size our jail and reduce case processing times. Our biggest challenge moving forward is reducing racial and ethnic disparities. Underlying community challenges in St. Louis County such as substance use, poverty, unemployment, homelessness, mental illness and lack of education exacerbate racial and ethnic disparities. Resolving these chronic problems demands coordination among many different county stakeholders and agencies – both public and private. We will continue to look for solutions at the intersection of justice and social services in the community. We are grateful for the MacArthur Foundation and the opportunity to be a part of the SJC. This work takes time and we have stumbled along the way, but it is possible with sustained effort. We encourage other communities to put the effort into justice system reform. Our story is one of many changes and shows how much people want to reform the justice system.

NACo would like to thank Christine Bertelson, Director of Strategic Communications for the St. Louis County Circuit Court, and Dr. Beth Huebner, professor at The University of Missouri-St. Louis, for speaking with us about their efforts

This blog post originally appeared on www.naco.org.