Community Engagement Data Analysis Incarceration Trends August 3, 2022

As I step down from a Safety and Justice Challenge role I’ve served in since 2015, I’m proud of what we achieved together in Charleston, SC and hopeful for the future of justice reform. I am optimistic the progress can provide a path for other communities to sustainably improve their local systems while safely reducing the misuse and overuse of jails.

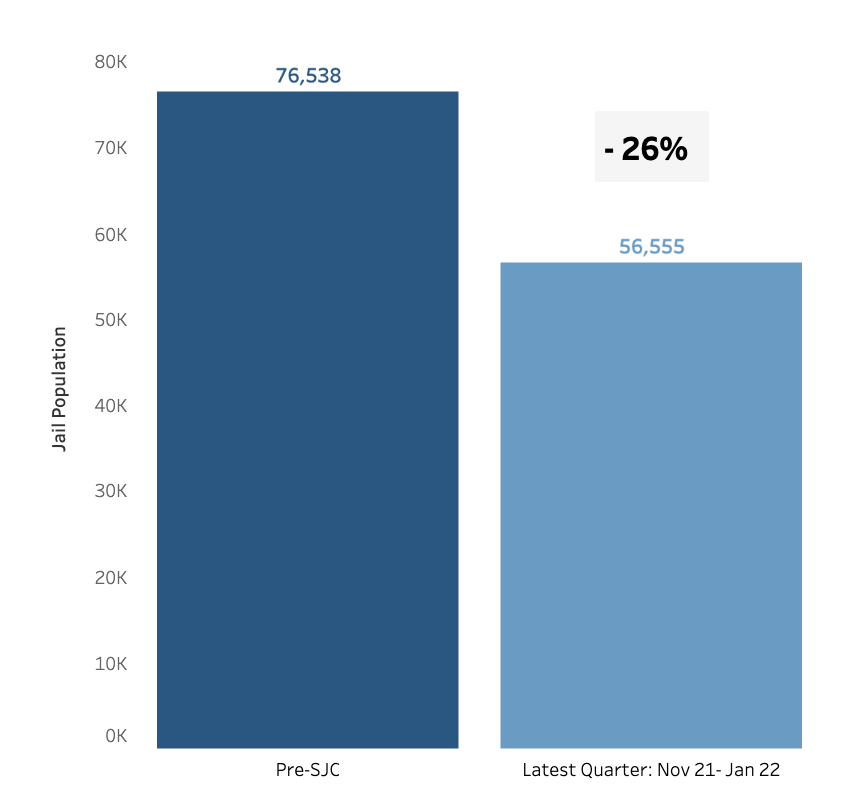

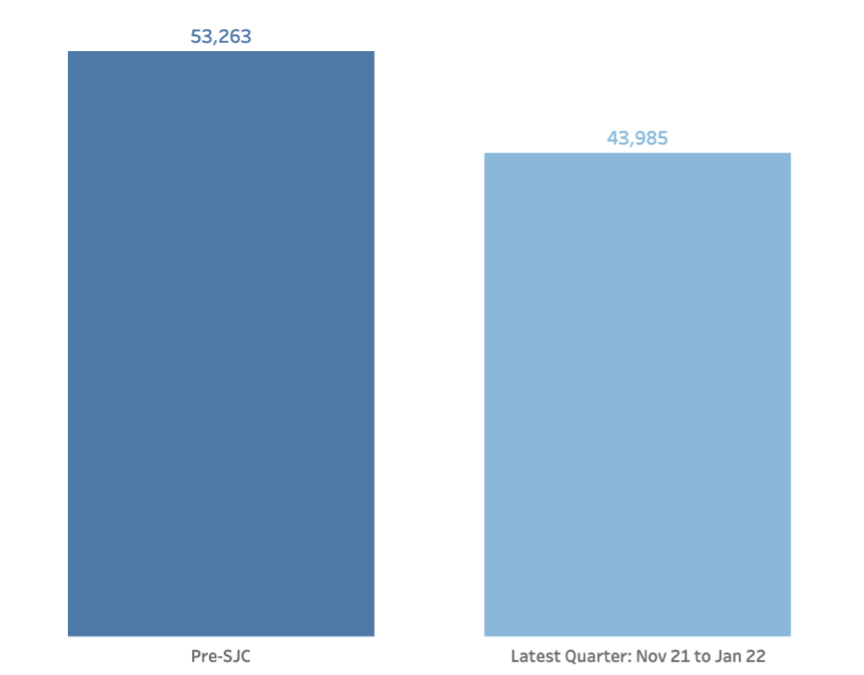

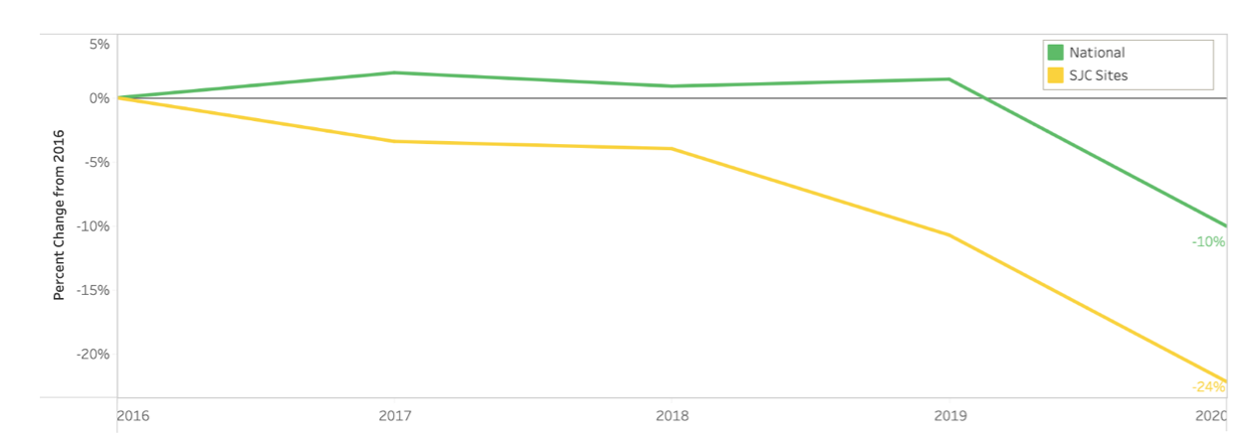

As reported in our 2021 Annual Report, Charleston County’s local jail population was reduced 40 percent from our initial baseline in 2014 to 2021. Municipal and Magistrate charges booked into our jail were cut by 80 percent. The rate of local bookings among our adult population decreased by 67 percent. The rate of local bookings among Black adults decreased from 178 per 1,000 Black adults to 58. The number of unique individuals repeatedly cycling through our jail, most often on lower-level charges, decreased by 71 percent. At the same time, Circuit Court charges booked into our jail kept steady and our crime trends remained similar to that in the rest of our state–which did not enact our reforms. We now have even more refined data and expertise to lead the way forward in making our local system more effective, equitable and efficient.

Those results have not happened by accident. They are the result of intentional data-guided collaborations between diverse stakeholders in Charleston, from executives leading agencies within the system to diverse members of our community. We came together, cutting across lines of responsibility and power, to objectively look at how our system was serving all of us and found sustainable ways to do more good than harm. We made it better by forming a Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC), assuming nothing, rethinking expectations, and continually using data to guide us. While there is more work to be done, the CJCC’s efforts moving forward will continue to be focused and intentional. For instance, the evidence-base is clearly pointing the way forward to reducing the time from arrest to disposition and improving pretrial outcomes.

Before joining the SJC I experienced the gap between what jurisdictions and/or independent justice system agencies were trying to do with reform measures and what was happening on the ground in local communities. If you have seen my TEDx talk you know my journey led me from experiencing the system first-hand, to working on the front lines in probation and parole, to working within organizations and legislative spaces trying to bring about greater alignment between what the research shows works and what actually happens, day-in and day-out.

Wherever I was working in the country, the gap between intentions for reform, and what was happening on the ground, persisted. It was natural because change is challenging. The challenges are also exacerbated by the constant barrage of hot button issues in the news. I found that jurisdictions often whacked one mole on the road to reform, only to find another mole pop up. It was disorienting and exhausting. I’d had enough of the reactive whack-a-mole approach and wanted to take a more proactive and sustainable localized approach to reform.

I came to realize if I really wanted to help make a system work better for the families and communities it served, I had to go local, and it had to be done with a collective body of system leaders and representatives of the community they served. I was convinced if we singularly focused our reform efforts on pulling one policy lever or another, or focused too much on one decision-maker or another, reforms would continue to come up short. To truly reform the system, we had to focus on the whole system.

Every decision-maker in the “system” and every decision mattered. Together, we could form a CJCC, assess how our system was working, set specific goals, and measure progress against those goals. After a lot of reflection, I came up with my dream job. I wanted to work hand-in-hand with local system actors and the communities they served. I wanted to form a CJCC, to use data to ground the dialogue, and to look beyond the next mole that pops up. While I was convinced this had to be the way forward, there were not many others willing to give it a shot, and there were no staffed CJCCs in South Carolina.

Then along came MacArthur’s Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC). When it launched, I stepped up to serve as a volunteer in Charleston alongside some brave early adopters. Together, we eventually formed the Charleston CJCC. We challenged one another, learned from each other, and became one of the first communities to join SJC. Over the last seven years, our CJCC has grown. It went from a scrappy startup to a mainstay in the community leading the way for others. While we remain the only community from South Carolina in the SJC, additional CJCCs are forming across the state. The collaborative, data-guided work of our CJCC is also contributing to the development of the first-ever national standards for CJCCs.

My vision is to see this kind of transformation take place across the country. There are roughly 3,000 counties across America and many of them lack the kind of sustained data-guided collaboration we have managed to pull together in Charleston and across many SJC cities and counties. Every community can and should have a high-functioning CJCC that brings diverse stakeholders together to look at its data, to see how its system is functioning, set specific goals, monitor their progress, and make it happen. Inevitably, the data will point to inefficiencies and inequities and countless stories of harms done. The data will also point to a number of opportunities to do more good than harm. I implore anyone reading this to be on the lookout for the forthcoming CJCC national standards published by the National Institute of Corrections in conjunction with the National Network of CJCCs and to strive to live them out.

As criminal justice reforms continue to evolve, I urge my colleagues to embrace data and constructive dialogue as their guide, stay focused on what makes their community safer and more just, and keep coming together. CJCC’s provide a sustainable forum for us all to demand collective accountability from the entire system and foster the learning environment necessary to make it happen.

Personally, it has been a challenging and rewarding experience to get to live out this journey, and I am excited for the continued efforts of the Charleston CJCC and CJCCs across the country. Meanwhile, I am also a mother who feels like time is moving way too fast. So, I am about to embark on my next journey to spend more time with my kids. For now, I am taking a step back from full-time work before that brief window of childhood closes and the next chapter opens.

I wish my colleagues at SJC sites across the country continued success as we continue to collaborate locally and across the country to do more good than harm.