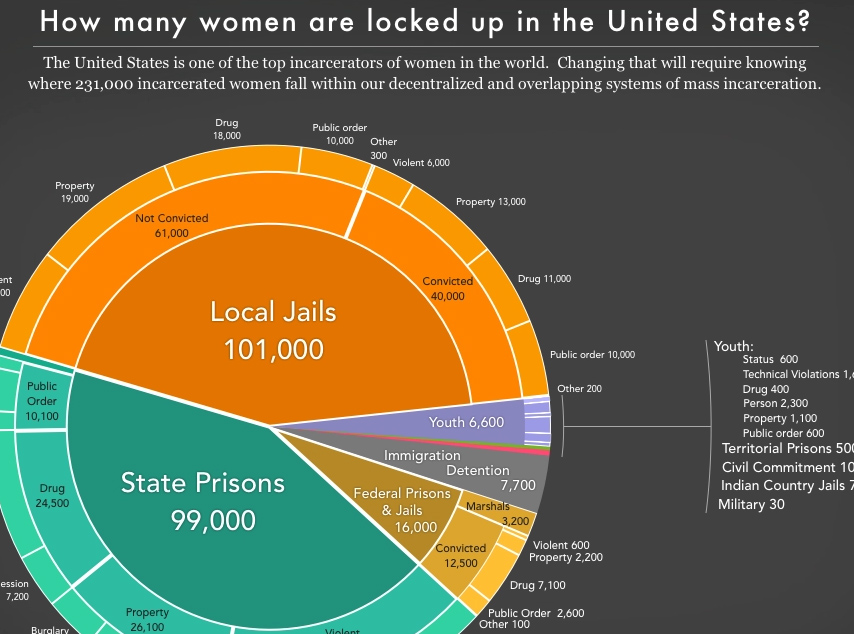

Community Engagement Jail Populations Policing February 12, 2020

Depending on one’s perspective, the role of law enforcement is often summarized into catchy but vague terms; peacekeeper, guardian, warrior, gatekeeper, savior, and enforcer are some of the most common. But none completely captures the multifaceted role we often play in communities around the world.

To a survivor of domestic violence or a parent with a choking infant, a police officer, sheriff’s deputy, or trooper might be a welcome source of support. To someone who was swept up as part of a “tough on crime” initiative, law enforcement officers are often viewed as warriors or enforcers.

The history of law enforcement shows that these roles are dynamic and change over time. In many communities, law enforcement agencies are at a critical nexus of redefining their role as gatekeepers to the criminal justice system.

With this in mind, the Vera Institute of Justice recently released a report entitled “Gatekeepers: The Role of Police in Ending Mass Incarceration,” outlining a roadmap to change which includes a series of recommendations that go beyond encouraging the establishment of alternatives to arrest programs.

The report delves into the need to address structural factors to alleviate the pressure on law enforcement agencies to arrest, and outlines how to do this through partnerships with other stakeholders such as community-based service providers and elected officials.

It’s important that we reinforce this point— that while the title of the report focuses on police and other law enforcement officials as “gatekeepers,” the report’s substance goes much deeper, highlighting the need for community-wide collaboration, and making it very clear that responsibility for the shift away from mass incarceration goes far beyond law enforcement, alone.

In truth, most individuals enter the field of law enforcement to help people and would rather have other options beyond arrest to respond to public safety challenges. In simplest terms, law enforcement officers do not want to bring people to jail at all hours of the day and night any more than people want to be brought to jail – particularly when alternatives to arrest, if available, would be a far better tool.

In areas where alternatives to arrest and/or booking exist, law enforcement takes full advantage of these non-punitive options, which is better for the citizen with whom they’re dealing, and gets officers back on the street and able to respond to calls for service faster and interdict violent crime. However, when options and discretion are limited, jail becomes the default. Law enforcement cannot reduce custodial arrests alone; government at all levels must work to provide alternatives.

Alternatives to arrest practices, like pre-arrest diversion and the use of crisis response or triage centers, show great promise to reduce both the collateral consequences of contact with the justice system and recidivism. This paradigm shift to increase law enforcement discretion to use non-punitive options is growing in the work of both local police agencies and national entities.

There are plenty of good local examples, but here are two:

- Tallahassee/Leon County, Florida Pre-Arrest Diversion, Adult Civil Citation (ACC) program: A four-year evaluation of this program, which started in 2013, showed that law enforcement, working directly in partnership with community-based behavioral health professionals, reduced the recidivism rate by approximately 80% for program participants. In addition, the 84% of participants who successfully completed the program avoided arrest records and any accompanying collateral consequences. Legislation passed in Florida in 2018 mandates Adult Civil Citation programs in every Florida county, leading to improved public safety, reduced impact on human dignity, and future opportunities by avoiding the life-long consequences of an arrest record.

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin, The Sisters Program: From 2013 to 2015, 704 women were arrested in Milwaukee 1,292 times, and 83% of those arrests occurred in just two police districts. The Sisters Program is a community-police partnership that offers diversion from the justice system, giving women the opportunity to change their lives and avoid future incarceration, fines, or other judgements. The Sisters Program is designed to create a citywide policy that uses a public health-based approach to street prostitution and sex trafficking, rather than a criminal justice approach that criminalizes women. Women diverted by the Milwaukee Police Department to the Program are connected to a variety of resources, including crisis management, counseling, advocacy, assistance with obtaining housing, and other critical resources.

On the national level, beyond participating in the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) has worked on several projects to promote justice system change and support law enforcement efforts to build stronger community-police relationships. Through these projects, IACP has created resources to support law enforcement in pretrial justice reform, conducted a study of citation-in-lieu of arrest programs that demonstrates widespread support for this practice, and created the One Mind Campaign to ensure successful interactions between police officers and people affected by mental illness.

So, how does this shift in culture and practices occur?

The reality in many communities is that few services are available all day, all night, and all year round, as law enforcement are, so they become the default resource for immediate help. Incidentally, that’s why people tend to call upon the police for so many different things.

Growing the capacity and availability of community-based treatment and services in order to create options for police—like diversion programs and community drop-off centers—takes collaboration among several local systems, including justice, behavioral and public health, medical, and local government. To be clear, having these resources available will reduce the reliance on a criminal justice response.

Additionally, creating 24/7/365 non-emergency help hotlines in communities can also reduce the reliance on law enforcement so that their calls for service are for instances in which there are public safety concerns.

These recommendations may seem simple and straightforward, but the process of implementing them can be complex. By working collaboratively with community-based partners, stakeholders can begin to identify gaps in treatment service capacity and combine expertise to work on system-wide solutions to fill those gaps, including identifying sources of state and federal funding and combining or co-locating local resources.

For many justice system agencies, the need for alternatives is evident, but the path to establishing them is uncertain. The wide variety of alternatives to arrest that communities and law enforcement are using can be overwhelming; it raises questions of what is the “best” or “most effective” approach.

There are also competing interests between addressing the real need for restructuring how communities seek and provide help versus gaining traction and showing progress by tackling the low-hanging fruit. New approaches might be difficult to introduce to the rank and file, such as the concept of harm reduction, which is a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use. Alternatives to arrest that incorporate harm reduction may be foreign to law enforcement who were trained to act on a binary choice – whether or not the person they are dealing with has “done wrong”.

This uncertainty should not be a barrier to exploring alternatives to arrest, however. It should be an incentive. When there is uncertainty, innovation can thrive. The climate is ripe for new ideas that go beyond low-hanging fruit and create deeper structural changes.

In the end, criminal justice reform is not simply police reform. We welcome and encourage all efforts to provide law enforcement officers meaningful alternatives to arrest to better serve our communities.

—Dr. Ronal Serpas retired in 2014 as Chief of Police in New Orleans, Louisiana. Previously he was Chief of Police in Nashville, Tennessee, between 2004 and 2010, and Chief of the Washington State Patrol between 2001 and 2004. He is now a Professor of Practice in the Criminology Department at Loyola University, New Orleans, and is the Executive Director of Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration. He is a past Vice President and member of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP).