Data Analysis Jail Populations Racial Disparities January 19, 2022

Cities and counties participating in the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) significantly reduced their jail populations over the past few years – both prior to and following the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite that progress, racial and ethnic disparities in jails persist.

Today the SJC has selected four jurisdictions to join a new Racial Equity Cohort based on proposals that explicitly focus on racial and ethnic equity in the criminal justice system; center lived experiences of Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other people of color; and emphasize the SJC Community Engagement Pillars of authenticity, accessibility and transparency, respect for diversity, and commitment to ongoing engagement.

The four cities and counties selected to participate in the Racial Equity Cohort are Cook County (IL), New Orleans (LA), Philadelphia (PA), and Pima County (AZ).

The funding will provide training and technical assistance focused on racial equity and authentic community engagement, peer-to-peer support from other cohort members, and qualitative and quantitative data and analytic support. The new funding and support announced is part of that commitment to learning and investing in more intentional and effective strategies to eliminate institutional and systemic racism within the justice system.

In that context, let’s take a deeper look at the data on racial disparities in jails and why there is such a great need for this work.

Jail Populations Can Be Successfully Reduced

Data collected by ISLG show significant declines in overall and pretrial jail populations, and reduced jail populations for people of color across SJC sites. Jail bookings are down, particularly for people charged with misdemeanors.

Since the start of the SJC, participating cities and counties collectively reduced their jail populations by 26% as of November 2021. This equates to almost 19,765 fewer people held in jail in SJC communities since we began collecting data. The decline in the confined pretrial/awaiting action population accounted for 52% of the overall decline in jail populations across SJC cities and counties.

Despite Improved Outcomes, Disparities Persist

Though jail populations are down across racial and ethnic groups, disparities persist in jail populations. While many people admitted to jail are released within hours or days of their booking, many cannot afford to post bail and may remain behind bars for weeks or even months. These and other burdens of jail fall disproportionately on communities of color.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, jail populations declined dramatically across the country and in cities and counties participating in SJC. Though declines in jail populations and bookings were prevalent across racial and ethnic groups, the declines were more pronounced for White people than for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people. As a result, racial and ethnic disparities persisted or worsened in many SJC communities between February 2020 and October 2020. The disparities were particularly deep for Black and Indigenous people.

More SJC Communities Reduced Jail Populations for White People

Though jail populations have rebounded somewhat since the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, jail populations are still below February 2020 levels in many sites.

Still, in most sites the reductions for white people were greater than the reductions for people of color, resulting in persistent disparities.

From when communities joined the SJC through November 2021:

- Jail population declines for Black people equalled or exceeded declines for White people in only 3 of 17 reporting sites.

- White jail populations declined more than Latinx jail populations in all 12 reporting sites.

- Indigenous jail populations out-declined White jail populations in 2 of 4 reporting sites.

Trends in Individual SJC Communities

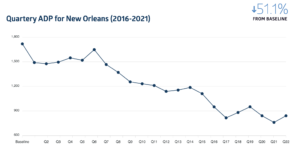

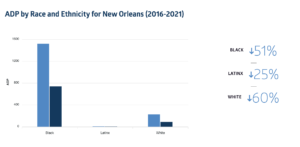

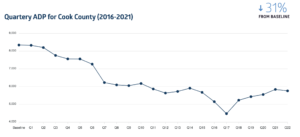

Data on the four racial equity cohort sites–New Orleans, Cook County, Pima County, and Philadelphia–further illustrate the persistent disparities that exist, even among sites that have made significant progress in reducing overall jail populations.

In New Orleans, Louisiana, the overall jail population declined by more than half since their baseline, but the reduction was more pronounced for white people (60% drop) relative to Black people (51% drop) and Latinx people (25% drop).

In Cook County, Illinois, the trends are similar. The t jail population ticked up slightly following the pandemic but remains significantly lower than baseline (down by 31%).. Still, the reductions in ADP for White people far outpaced reductions for Black and Latinx people.

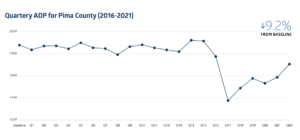

In Pima County, Arizona, race and ethnicity trends are unclear–local partners will be working on expanding their capacity to track this data as part of their reform work. Overall, however, the jurisdiction’s jail population trends show a 9% decline from their baseline and an upticksince the initial months of the pandemic.

Philadelphia, like Pima, does not yet fully report race population breakdowns, but has seen an overall jail population decline of 39%, up slightly from a pandemic-era low.

Work to Eliminate Disparities Continues

As cities and counties continue to implement strategies to safely reduce jail populations, more work remains to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities. The new SJC racial equity cohort in select sites across the country is an opportunity to further reduce harm and implement best practices.

–The SJC has engaged the Institute for State and Local Governance (ISLG) at the City University of New York (CUNY) to track data across participating cities and counties.