A pivotal moment has come in the long and complex effort to reform the U.S. criminal justice system. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has directed officials in Alameda County, California, to fundamentally change the way it deals with people with mental illness.

DOJ did so by issuing a formal “letter of findings“, taking the county to task for failing to meet the needs of people with mental illness and entangling them in the criminal justice system. Policy makers and lawyers are watching the situation closely, and the outcome is likely to have an impact far beyond the Bay Area.

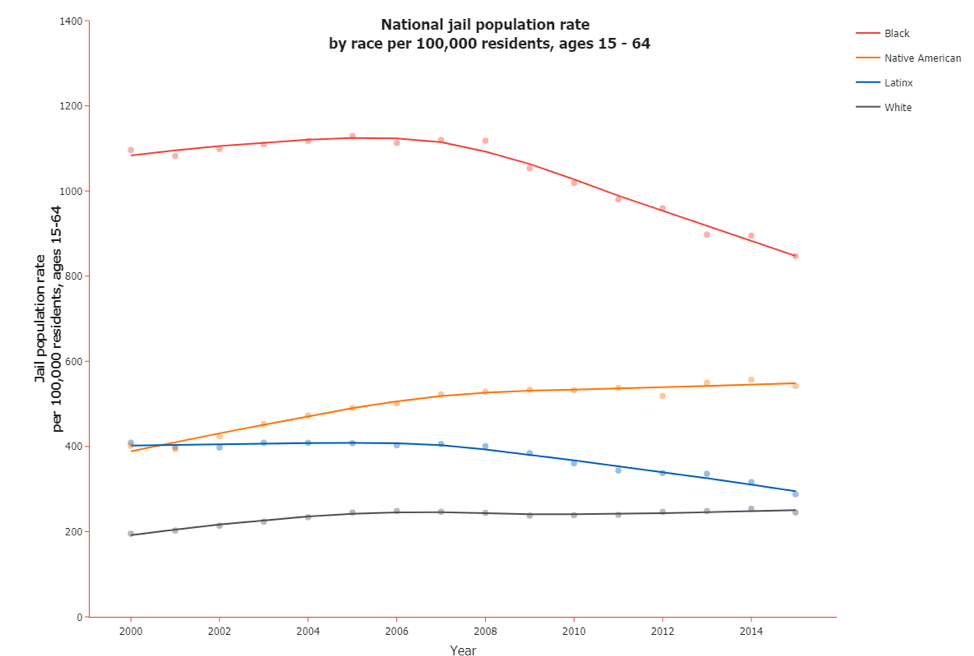

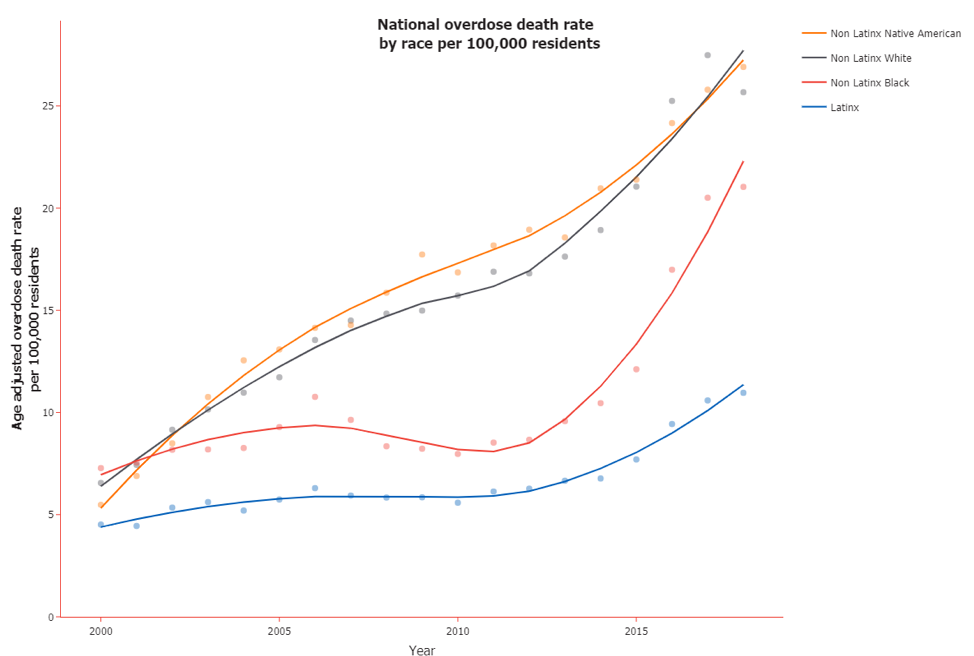

The DOJ letter recognizes that people with serious mental illness can live productive lives in our communities. Many of them do so by receiving services funded by the government, such as mental health treatment, peer supports, and housing. Many others, however, do not get the services they need, and those individuals are disproportionately Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Among those who lack services are people commonly called “frequent fliers.” People with mental illness are repeatedly jailed for low-level offenses such as trespassing, shoplifting, and disorderly conduct. Their mental health care consists of visits to emergency rooms and short hospital stays. They typically lack stable housing. They cycle between jails, hospitals, and the streets.

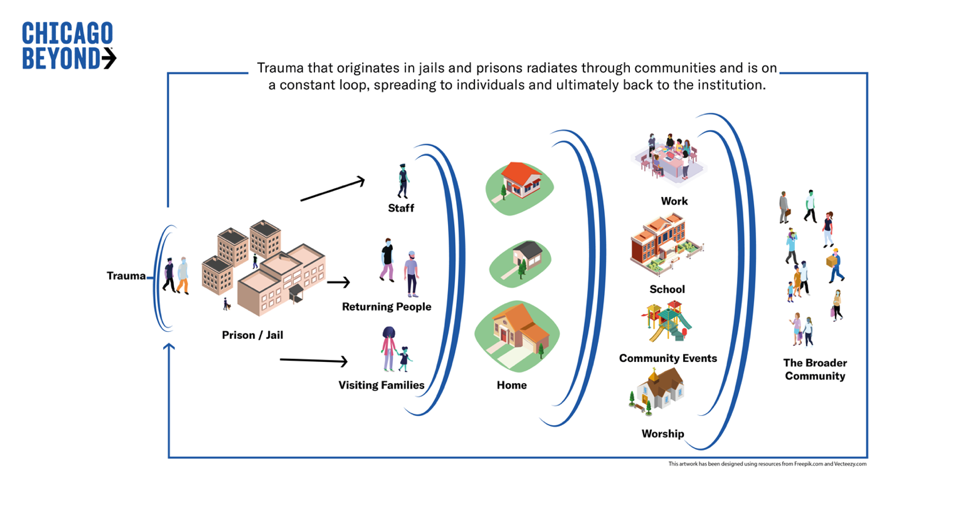

The Cycle as a Single, Failing System of Care

The DOJ letter is a turning point in remedying the cruel trap that this cycle creates, harming people with mental illness, their families, and their communities. The letter recognizes that, as a practical matter, jails, emergency rooms, and hospitals operate as a single, failing system of care. The letter requires the county to abandon that failed system and instead provide community-based treatment and housing to people who cycle in and out of the criminal justice system. It directs the county to deliver evidence-based mental health services, such as mobile crisis teams, assertive community treatment, intensive case management, peer support, supported employment, and supported housing.

DOJ’s letter shows that the political and legal landscape is changing. The letter is a sign of new priorities, reflecting a changed federal approach to criminal justice reform. And it also reflects a renewed federal commitment to civil rights enforcement. Much of the letter is a legal analysis of why Alameda County’s practices violate the Americans with Disabilities Act, a federal statute, enforced by DOJ, prohibiting discrimination against people with disabilities, including people whose disabilities stem from mental illness.

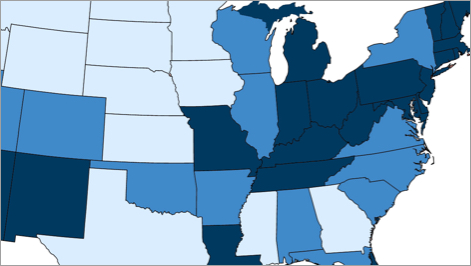

Assuring that people who cycle in and out of jails get the community-based treatment and housing they need is not “pie-in-the-sky.” It is achievable. The expertise exists. The MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, which is helping to reduce jail populations across the country, has provided a blueprint.

First, we must identify the individuals who are trapped in the cycle and work with them to identify better ways of providing them services. Second, we must invest in the community-based services we know are effective.

Fortunately, new federal funding is available through President Biden’s new American Rescue Plan. It increases the federal Medicaid contribution for community mental health services, including an 85% federal Medicaid contribution for the cost of mobile crisis teams. It also provides new federal funding for housing.

Funding can come as well from savings generated by reducing jail populations. When people with mental illness receive needed services, far fewer go to jail. Far fewer people in jail should yield substantial cost savings, which can be reallocated to pay for an expansion of community services.

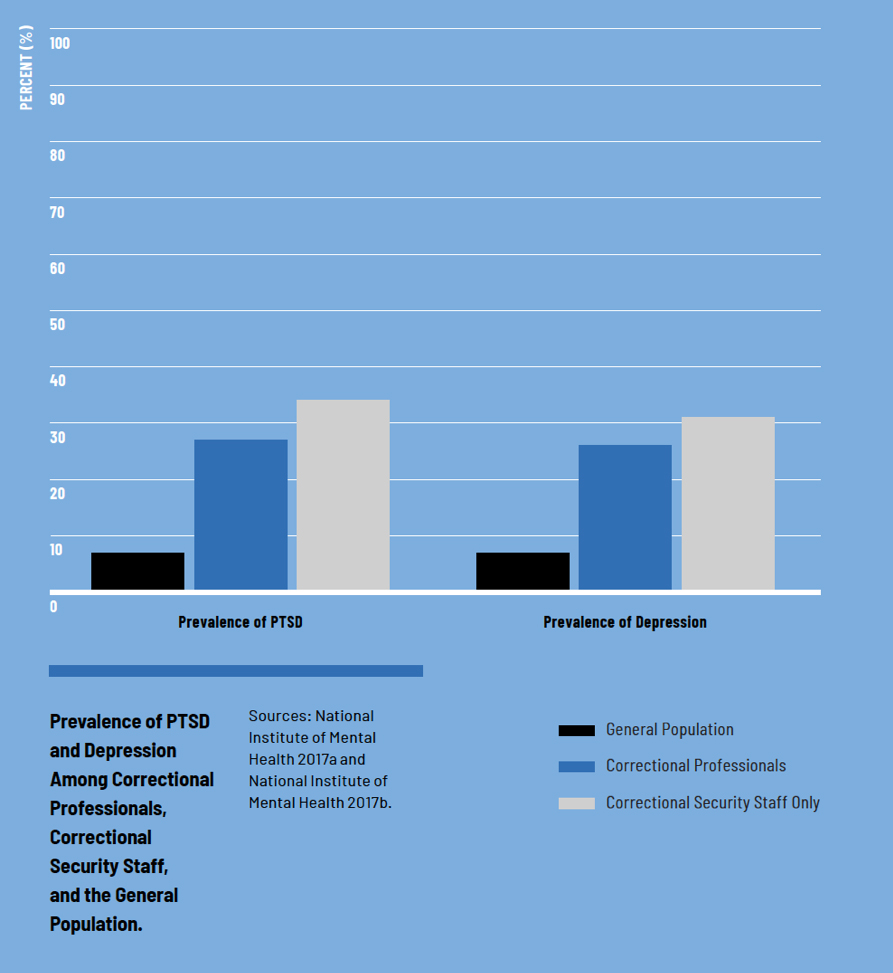

Third, we must shift responsibility from the criminal justice system to the mental health system. It is not acceptable to rely on the criminal justice system to address what is, at its core, a mental health care problem. Moreover, it is dangerous to have police respond when people with mental illness are in crisis or need services. Far too many people have been killed in such encounters. Fully one-quarter of the people killed in police shootings are people with mental illness.

The current system, which takes lives, also exacts an enormous financial cost. We are squandering millions of dollars on maintaining the trap of cycling. For example, it costs Alameda County in the vicinity of $120,000 per person per year for avoidable jail and hospital stays. For substantially less, it could provide an apartment and quality community-based treatment. It may be that Alameda County could fund the reforms sought by DOJ entirely from the money it spends on practices that consign many people with mental illness to repeated and avoidable stints in jail, hospitals, and the streets.

Taking these steps would dramatically improve, indeed transform, the lives of many people with mental illness. It would recognize them as deserving members of our communities with much to contribute. Taking these steps would also promote greater equity in the health care and criminal justice systems, since those who would benefit are disproportionately Black, Indigenous, and people of color.

No one should be caught in a futile system of harm. DOJ has now joined and given a big boost to the effort to dismantle that system and replace it with effective community-based treatment and housing. It will be a long road, but such systemic reform is within our grasp.