A successful misdemeanor diversion program at a Safety and Justice Challenge site in Durham County, North Carolina, can serve as inspiration for jurisdictions across the country as they seek to reduce jail populations and preserve public safety.

The diversion program shows collaboration between law enforcement and community groups in Durham County, and is the subject of an initial process evaluation by the Urban Institute, which you can download here.

The Urban Institute has not yet completed an accompanying outcome evaluation to see how the perceived impacts reported by relevant stakeholders align with measurable impacts available through local metrics —it is forthcoming in fall of 2021. But the county has been tracking its own numbers and it estimates that just under 800 people have gone through the program since 2014, with 99 percent of participants completing it. Of those, about 95 percent remain out of trouble after a year. Again, the Urban Institute—which is renowned for its rigorous, independent research—has yet to verify those numbers as an independent evaluator of the program. But in the meantime, the county is displaying them on its public-facing website as early evidence of the program’s success.

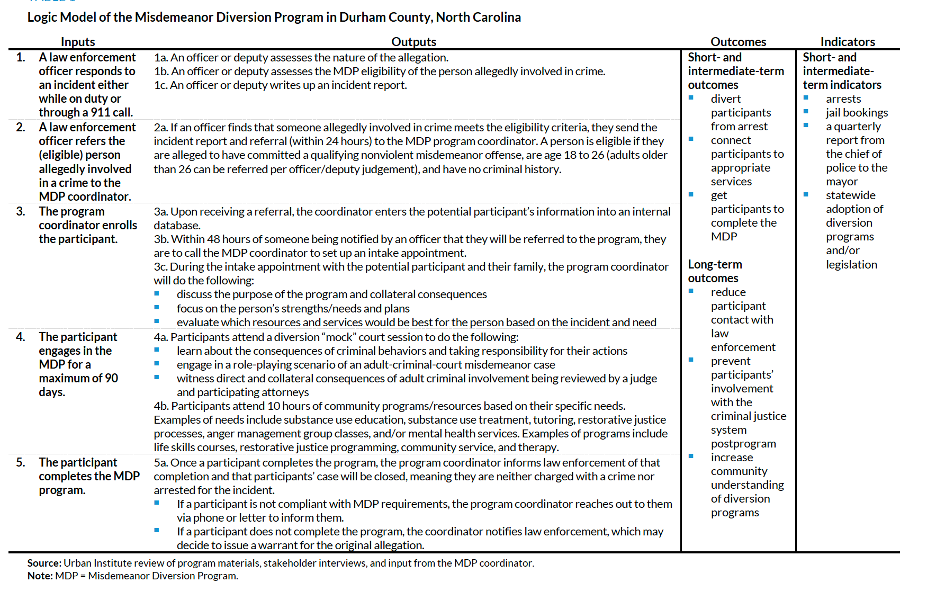

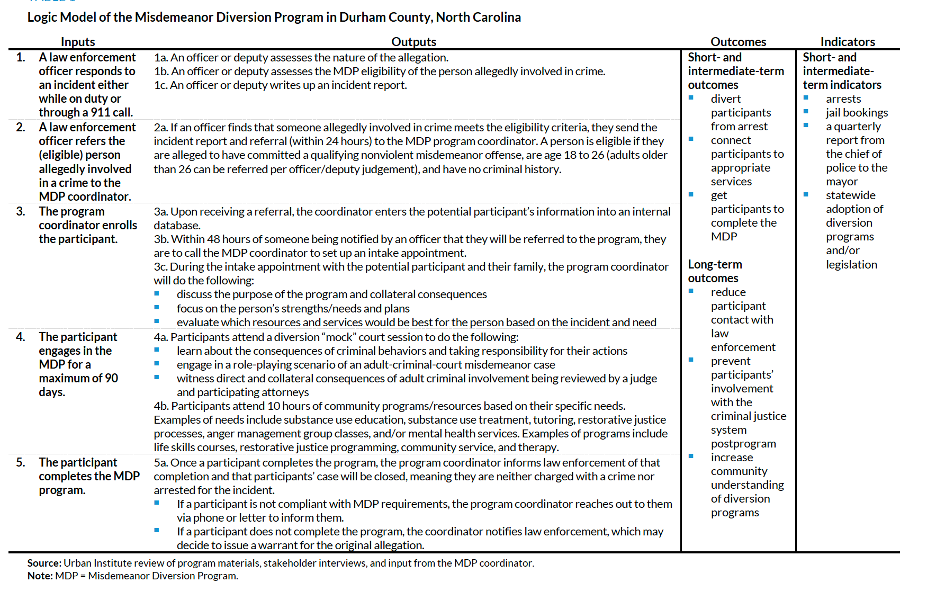

The Misdemeanor Diversion Program (MDP) began in 2014 to keep children out of the criminal justice system, because North Carolina had such antiquated laws related to minors. Until the ‘Raise the Age’ legislation passed in December, 2019, the state was automatically charging 16 and 17-year-olds as adults in the justice system and giving them adult criminal records.

The program allows law enforcement officers in Durham County to redirect people accused of committing their first misdemeanor crime(s) to community-based services in lieu of citation or arrest. What is unique about the program is that it occurs prearrest and pre-charge, meaning someone law enforcement officers may believe has committed a crime is not arrested or charged and does not formally enter the justice system in any way.

The program expanded to benefit adults up to 26, with older adults at law enforcement discretion. And other jurisdictions have replicated it across the state. It was based on a simple foundational principle: The need to avoid involvement in the justice system, where possible. It aimed to be as unrestrictive as possible while providing participants with the support necessary to move forward positively.

In the first week, the program got just two referrals. But a key element of the program’s success came in 2016 when the Durham Police Chief at the time created an executive order, taking discretion away from Durham Police officers and making referral of eligible individuals to the program mandatory for the Department.

The need for a program like the MDP in Durham County was well articulated by county stakeholders and participants who participated in the process evaluation. All stakeholders feel that people—youth in particular—do not need to be arrested and deserve “a second chance,” as some put it, if they do not pose a threat to public safety. Members of local law enforcement also believe the program has been useful and impactful. However, many local stakeholders believe that the community still needs more prearrest diversion opportunities whenever possible.

The program is cost effective and began with a grant, but it is now part of the county’s regular budget, demonstrating that it is replicable in other jurisdictions, with the right support and buy-in from local authorities.

Racial equity was also discussed during the conception of the program—given the disproportionate numbers of Black people in the county’s jail. Around three quarters of participants in the diversion program have been people of color.

Through interviews, we found that community stakeholders and program participants believe the MDP is impactful, particularly in that it diverts people from being charged with a crime and entering the justice system. Interviewees also generally believe the program was deeply needed in Durham County because too many people were being unnecessarily arrested and incarcerated.

Our process evaluation yielded four key takeaways for jurisdictions interested in replicating the MDP. First, buy-in from law enforcement is critical because it is needed to start the diversion process. Second, support from local leaders, such as elected officials, will help develop local law enforcement buy-in and support. Third, qualified program staff with deep community connections are essential. And fourth, a philosophy of keeping people out of the justice system altogether will lead to increased participant satisfaction and reduce collateral consequences associated with any justice involvement.

None of the interviewed stakeholders expressed resistance to the program, but several noted that when it was being developed, there was notable resistance from law enforcement agencies and law enforcement associations. Most of that resistance involved concern among local law enforcement officers that the program could take away their ability to determine whether an arrest could be made in certain situations, an ongoing concern during the early years of program implementation. In addition, numerous officers believed this type of program would infringe on their ability to perform their duty and would override their power to use discretion. Over time—through trainings, interactions with the program staff and participants, and changes in law enforcement leadership—law enforcement agencies generally became more supportive of the program.

Several stakeholders strongly support the program but believe it does not “do enough” (in the words of one interviewee) to reduce countywide arrests and incarceration. They want it to expand eligibility requirements to include more offenses, including additional misdemeanor charges and some felony charges. Simply put, many stakeholders feel the program has positively impacted participants but that too few people have been able to participate, leaving more people involved in the local justice system than necessary.

Some stakeholders criticized the program for making eligibility requirements too restrictive and not allowing enough access the program, which they consider essential to diverting people from the criminal justice system pre-charge. Many interviewees believe other communities would benefit from implementing similar programs to divert people from the justice system.

We encourage people to read the full process evaluation and to develop their own diversion programs based on what has been learned in North Carolina.