Data Analysis Incarceration Trends Probation January 12, 2023

Jurisdictions across the country can learn from efforts to study probation violations in-depth. A new report on probation violations as a driver of jail time in St. Louis County, Missouri shows that expediated probation programs have much to offer and can work to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in the system.

Probation matters. More people are under probation supervision in America than any other correctional sanction. One in 84 adult U.S. residents is on probation right now, which increases the risk for later imprisonment. As an initiative of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) is seeking to reduce jail populations. So, looking at probation violations is an important step toward doing that. Most of the current research on jail reform has considered the pretrial population, but we know less about individuals returned to jail for a probation technical violation, which includes failure to meet the conditions of probation supervision (e.g., maintaining employment, regular office visits, and routine drug tests).

We looked at the probation revocation process in St. Louis County, an SJC site. Before joining the SJC, the county’s jail population had been either near or over capacity for over a decade. But it has reduced average jail populations by 30% since 2016 through a series of measures.

We looked at how long people who violated probation in St. Louis County were detained in jail, and race differences in jail admission and length of stay trends. We also used a racial equity framework for the study to see if jail reform efforts harmed or helped people of color. As part of this work, we evaluated the county’s Expedited Probation Program (EPP). This program was implemented as part of the SJC reform efforts and is designed to speed up case processing and provide services for people detained on a probation violation.

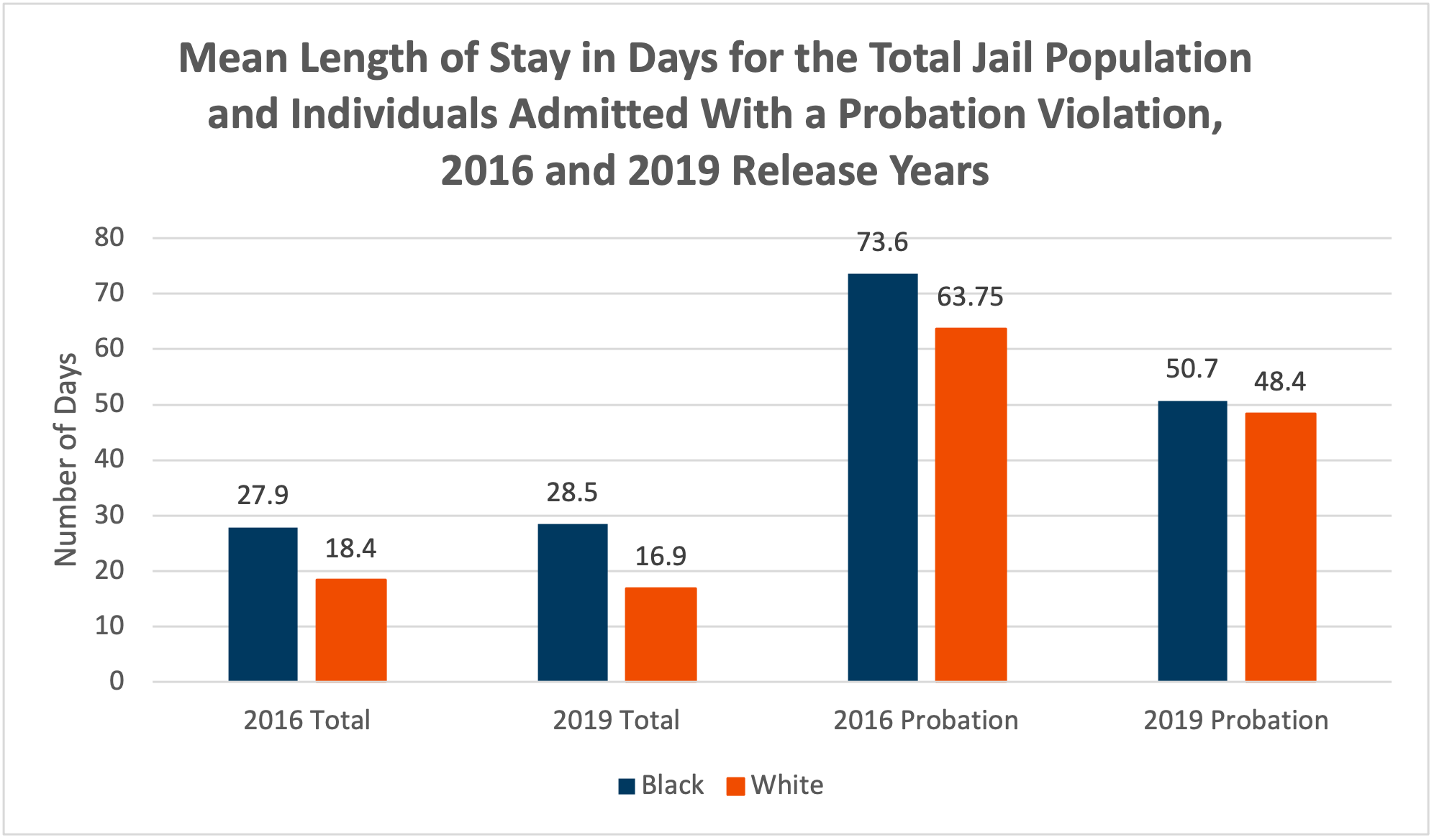

We found that individuals who are booked into jail for probation violations represent a small part of the total jail population in St. Louis County, but they have substantially longer lengths of stay than other groups. The length of stay for people on probation declined by 33% from 2016 to 2019, from 44 to 30 days. In comparison, the average length of stay for the total jail population remained stable at 23 days in 2016 and 2019.

While Black individuals on probation had longer lengths of stay than White individuals, we found that some racial disparities in length of stay have declined over time. Still, racial disparities remain in the jail population. While the county population is about two-thirds White and one-fourth Black, the 2016 and 2019 jail probation population was made up of about 54% Black individuals compared to about 45% White individuals.

Meanwhile, the EPP program provides evidence that reforms can reduce the length of time people on probation are in jail and an opportunity to learn about potential best practices. Broadly, the program is designed to expedite the revocation process to divert individuals from jail to community-based treatment. Unlike most correctional interventions, the primary aim of the project is to change how individuals are processed in jail instead of solely expecting individuals in the program to reform based on service provision. Specifically, the goal of the EPP is to have individuals evaluated by a judge and released within 10-12 days of incarceration.

The EPP model integrates evidence-based interventions including: 1) detailed coordination with members of the supervision team such as probation officers, jail case managers, and community treatment staff to ensure a continuum of care; 2) case coordination with a probation officer embedded in the jail; 3) treatment plans presented to judges for approval (reducing delays in the hearing process); and 4) warm handoffs and linkages to services.

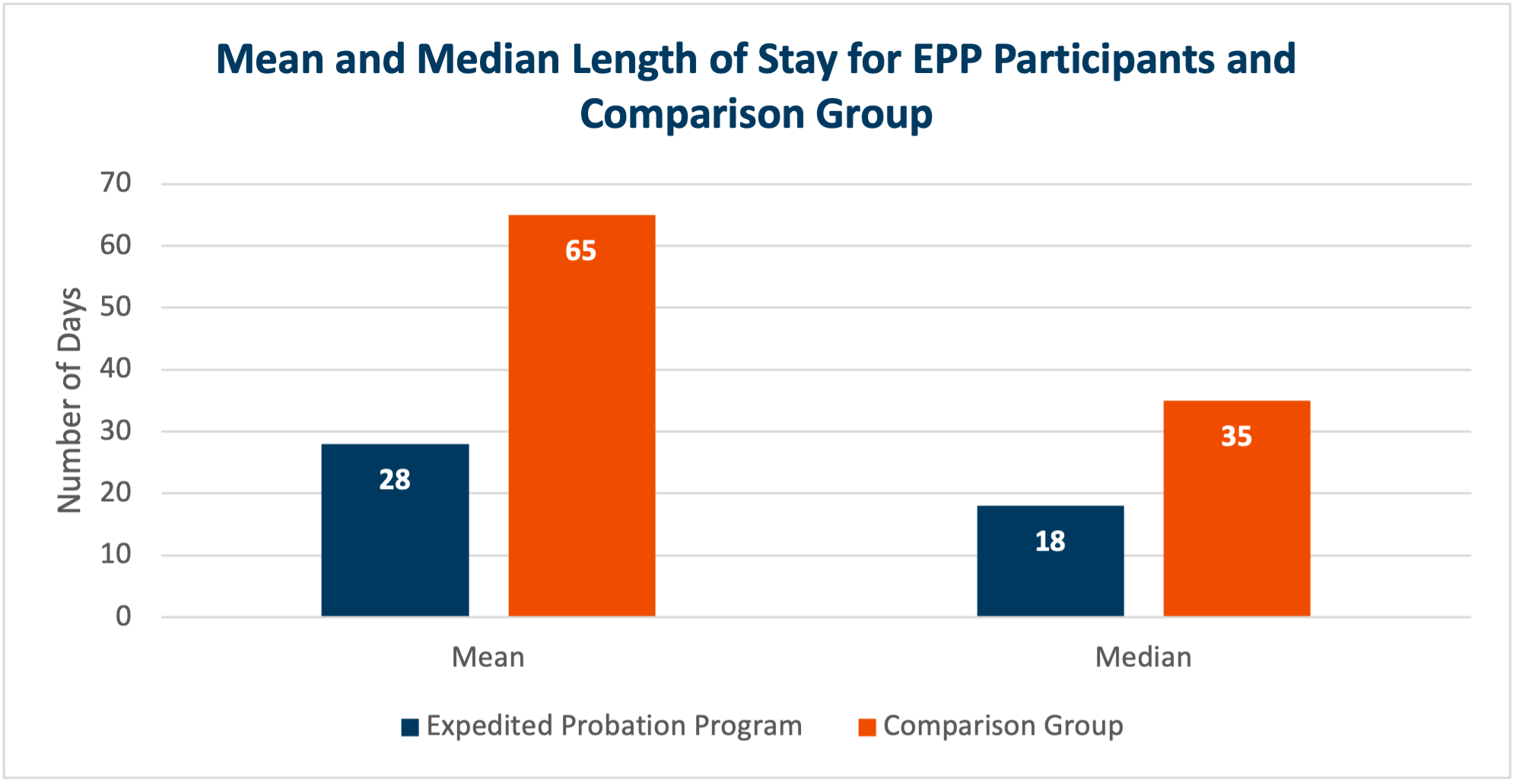

The Expedited Probation Program (EPP) achieved its goal of reducing the number of days individuals admitted to the program were detained in jail, and these reductions were substantial. On average, participants spent 28 days in jail compared to 65 days among people in a comparisons group who were not in the program. Further, the processing time continued to decline as the program progressed.

In addition, the implementation of the program led to a larger decline in the length of stay for Black individuals in the program. Although this effect needs to be explored in more detail, there is potential evidence that this type of change to case processing may be able to attenuate some of the racial disparities inherent in this part of the criminal legal system.

While the program was successful in reducing the number of days people were detained in jail, the recidivism rates were higher for the EPP group than for the comparison group. Interviews with program staff suggest that there is substantial stress and barriers to compliance with the court-mandated programming associated with the intervention, which may have led to higher rates of technical violations, like failure to meet conditions of substance abuse treatment or missing appointments, among the intervention group. Emerging from our interviews with stakeholders and system-involved people also indicated that people on probation have substantial unmet needs, many of which were related to substance use disorders and poverty. COVID-19 also has changed how the probation office Interacts with clients, shifting to a community-based model in which probation officers meet clients in the community or over Zoom. There is general support for these changes. In addition, many of the participants appreciated the ability to interact with the court virtually for probation violation hearings.

Overall, the results of the EPP program suggest that collaborative processes can be instituted to reduce the time spent in jail for a probation violation. That noted, to reduce the rates of recidivism among this group, more work needs to be conducted to better understand the needs of people released and how to best provide services to this group that facilitates long-term integration.