Pretrial Services Victims Women in Jail August 2, 2019

American jails are housing more women than ever before. Some studies show that in the last two decades, the number of women in jail has grown twice as fast as that of men.

In Maine, we have long recognized that women enter the criminal justice system with a complex set of needs, including an extensive history of victimization. An internal study from 2003 showed that 93% of women incarcerated in Maine experienced abuse prior to incarceration, with many experiencing abuse across their lifespan beginning in early childhood.[1] Until recently, however, we were unable to address this issue. We were granted the opportunity to reach underserved women who are incarcerated and provide vital services to address these complex needs with the receipt of a Safety and Justice Challenge Innovation Fund award.

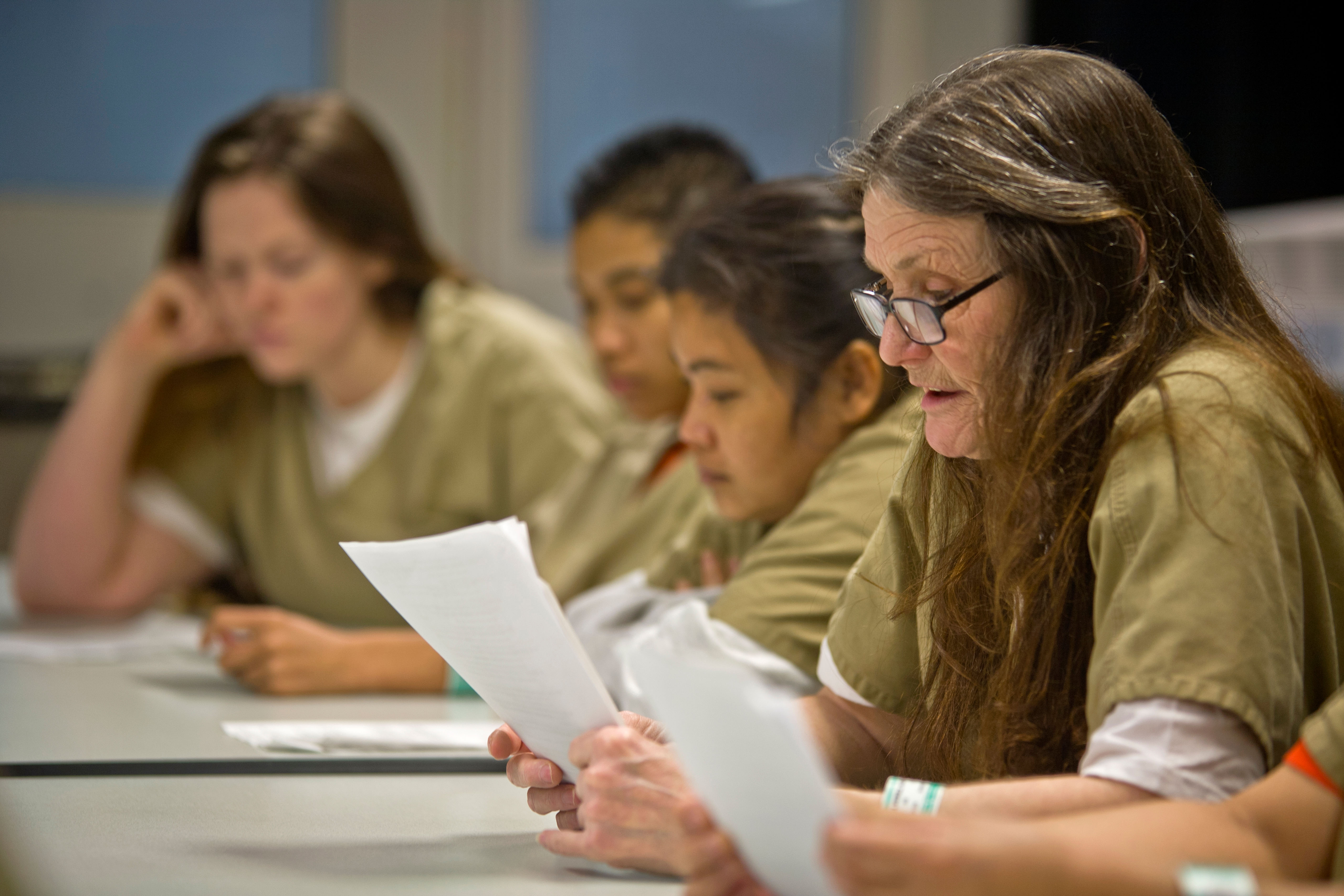

Through These Doors is the domestic violence resource center located in Cumberland County, Maine’s most urban county. Maine Pre-Trial Services (MPS) and Through These Doors (TTD) have a history of partnering to hold people charged with domestic violence crimes accountable and to keep survivors safe. Our new initiative—Project Safe Release—builds upon this existing partnership and works to provide services for even more people impacted by this issue.

Project Safe Release was developed as an effort to decrease the gaps in services for women who are incarcerated, identify women who are in need of trauma services, and coordinate services. We began by cross-training the staff at our organizations to make connections and build buy-in for the project. During the first quarter of the project, the training covered domestic violence dynamics, the history of pre-trial services, and service delivery. Working within the justice system to address survivors’ complex needs is a daunting task fraught with barriers; approaching this work in collaboration creates built-in support and camaraderie for employees. We then created protocols that will sustain the program for new staff, as well as written materials about our services and contact information.

The next step was to research, identify, and implement an assessment tool (we selected MOVERS: Measure of Victim Empowerment Related to Safety scale), and created a data system to monitor our progress. It is difficult to measure and quantify safety related to domestic and sexual violence because survivors do not have control over whether the abuse continues. The goal of MOVERS is to assess safety by measuring victim empowerment related to safety and understanding the level of empowerment survivors feel to manage their safety.

To date, 73 female defendants have been screened pre-arraignment at the Cumberland County Jail by MPS. Forty-five of these women self-identified as survivors of domestic and/or sexual violence. Of these 45, 38 voluntarily accepted written information about TTD and 26 signed release of information to allow for coordinated service delivery. Over the past nine months, there has been an increase in referrals to TTD and enhanced partnership between both organizations. An increase in referrals indicates that more women are connecting with TTD for comprehensive victim services during their incarceration and post- release, which we believe correlates with increased safety-related empowerment.

We are honored to be part of the Safety and Justice Challenge to provide vital services to incarcerated survivors. This project presents a unique opportunity to safely release women who are on pre-trial contracts while also ensuring their safety in the community from partners who cause harm, thereby reducing the amount of time women remain in custody awaiting court proceedings. As the project continues, we look forward to evaluating the data to determine if women report an increase in safety and sense of empowerment over time.

[1] “Building Bridges: A Support Group and Advocacy Program for Incarcerated Survivors of Domestic Violence in Cumberland County, Maine.” Kurzmann, Joanne (2003).