Data Analysis Racial and Ethnic Disparities April 26, 2022

Data analysis in criminal justice reform helps prevent us from acting on unexamined and invalid assumptions. It helps us check whether reforms are having the intended results. A great example of this is recent data analysis by my colleagues and me at the Center for Court Innovation. We looked at Population Review Teams (PRTs) in three sites supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge: Lucas County, Ohio; Pima County, Arizona; and St. Louis County, Missouri.

The PRTs generated good will at these SJC sites. They bring diverse stakeholders together and engage them in conversations they would not otherwise have. But digging into the numbers shows a more complicated story. In fact, PRTs do not substantially reduce jail populations on their own. Indeed, while they do help release some people, in some instances they release a disproportionate number of White people.

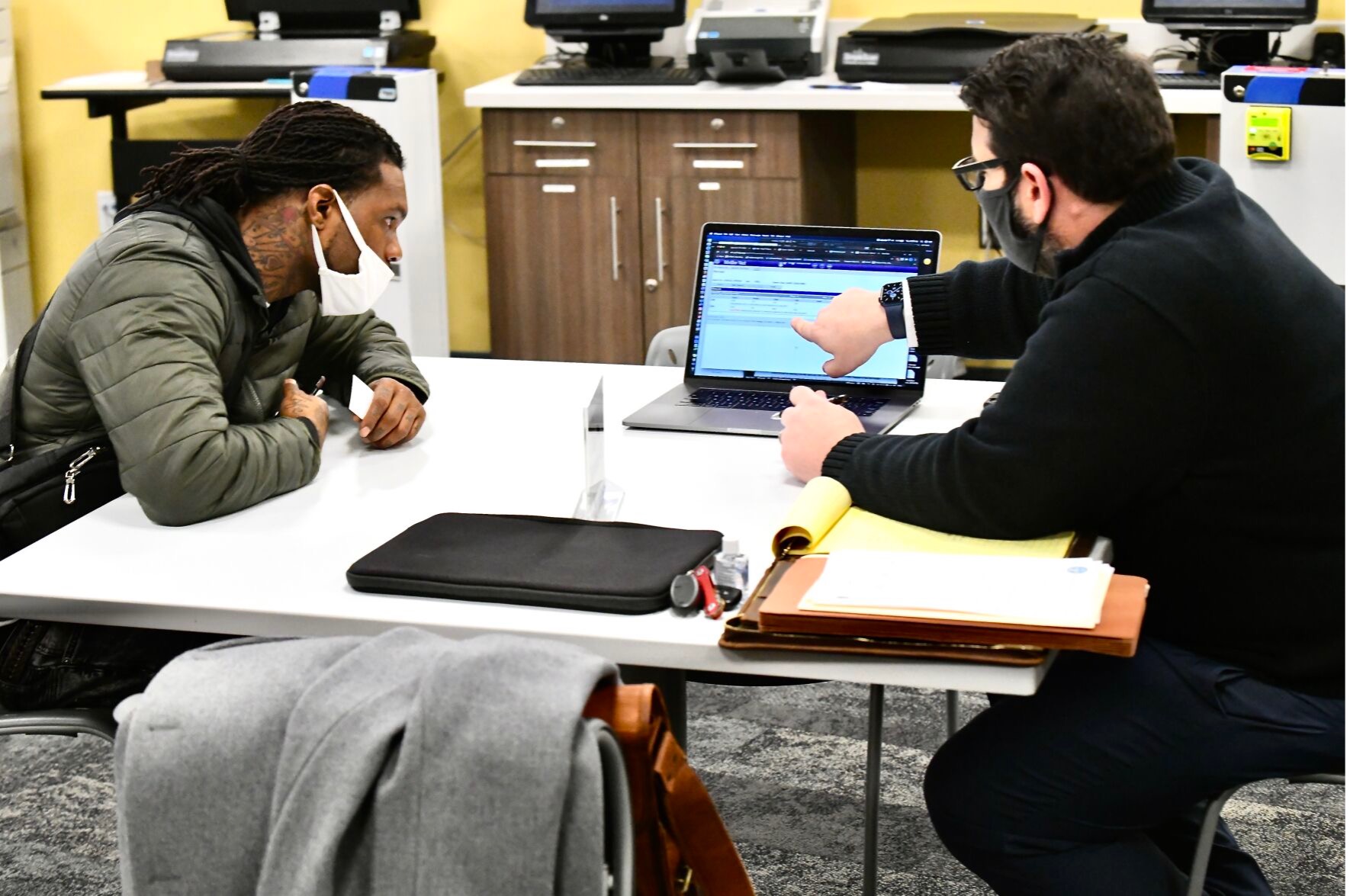

But the PRTs also foster deeper conversations. Those conversations focus on other ways stakeholders can change the justice system, and this is where teams can unlock more significant long-term value. The value of these conversations became clearer during COVID-19, for example. Jurisdictions were able to use the PRT structure to make quicker decisions about whom to release. As a result, there were fewer people in the jails during a dangerous time.

More detail on the numbers

The PRTs we examined resulted in the release of a small proportion of the total jail population (0.4% of the total jail population in Lucas County, 1.2% in Pima County, and 0.3% in St. Louis County). The PRTs have a larger impact once a case is chosen for review. For people that make it to this threshold, about half are released: 46% of reviewed cases are released in Lucas County, 48% in Pima County, and 47% in St. Louis County.

In addition, PRTs may have the unintended effect of increasing racial disparities. In St. Louis County, White individuals are 1.5 times more likely than Black individuals to get out of jail through the PRT process. White people are more likely to be eligible for and recommended by the PRT in the first place and then ultimately more likely to get out of jail. We also found that reducing racial disparities at early stages of the process is not enough to reduce disparities in who is released. In Lucas and Pima counties, Black individuals were more likely than White individuals to be eligible for review, but these differences disappeared after the initial eligibility stage. In other words, Black individuals were no more or less likely to be released.

Broader impacts and recommendations

Our findings spotlight the problem of expecting initiatives to reduce racial disparities when they are not explicitly designed to do so. PRTs need to overtly consider race during their development and adopt policies and practices that incorporate race.

Feedback from the sites also suggests that the current PRTs supplement and drive broad policy change. The PRTs engage stakeholders in meaningful collaboration and foster conversations about over-reliance on jail. And in Lucas and St. Louis counties the goals of the PRT are not limited to pretrial release; they also aim to move cases along by helping connect clients to attorneys and working out plea deals. These are valuable achievements that are not captured when we look exclusively at the number of releases.

We recommend jurisdictions draw on PRTs as a foundation for collaboration, collective problem solving, and informed decision making. They can also use the data to explore avenues for innovation, as happened during COVID-19. In addition, we recommend that jurisdictions reconsider who is eligible for PRT review, including explicit consideration of race and potentially expanding eligible charges.

Understanding that all sites have limitations to capacity and resources, we believe that transparent and intentional selection criteria are crucial to establishing a fair process. To this end, we recommend sites seek to improve the transparency of PRTs. Systematizing the steps involved in selecting people for review can help to reduce the influence of bias or excessive subjectivity and improve fairness.

We recommend increasing the number of people reviewed for release. One mechanism to do this is expanded eligibility criteria. St. Louis and Pima Counties are already considering such changes by expanding to include more charges, like people held on a violent charge or a probation violation. We also recommend using the PRT process to drive policy change. If PRT members, for example, see that a specific charge often results in a release, they could recommend pretrial supervision for such a charge as a de facto policy. This would keep more people out of jail and reserve PRT resources for more complex cases. Ongoing data review can help inform such policymaking.

PRTs are a first step, but the data suggests the teams can go further. Sites should use the data to inform PRT changes and the potential is there for broader impact.