December 3 is International Day of Persons with Disabilities. So, we spoke to leaders working in the area involved with the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) about what needs to change, and where there has been progress.

(From left to right: Chris Huff, Supreet Minhas, Candace Coleman and Jalyn Radzminski).

Chris Huff (he/him) is Diversion and Reentry Policy Analyst at Access Living—a center of service, advocacy, and social change for people with all kinds of disabilities, based in Chicago. In this role, Chris leads policy efforts centered on supporting people with disabilities impacted by the criminal justice system.

“I think we’re at an all-time high, right now, in terms of putting people with lived experience of disability and the justice system in the position to advocate for the changes that we need,” he said. “And I’m encouraged by that.”

The most discouraging part of his work is the lack of engagement and support from the law enforcement community to address the issue of working with people with disabilities. Oftentimes contact with law enforcement is a person’s first entry into the criminal justice system.

“To me, the root of these issues is that the system is not designed or intended to support people, but rather punish them,” he said. “Two thirds of survivors of crime say they prefer a system focused on rehabilitation than punishment, but we continue to run the system with that outdated mindset.”

When bringing up the idea of working to make the system more supportive of people with disabilities, Chris says he has been frustrated with responses that do not see that as part of the role of the criminal justice system.

“Even collecting data on people requires a level of clinical or social work-type training to be able to ask the questions in a proper way, to identify disabilities without being invasive or intrusive,” he said. “But to make that happen we need to have a sincere and aggressive interest in making it happen by law enforcement. And we’re not there yet.”

It matters to Chris to focus on more support and rehabilitation for people with disabilities in the criminal justice system because it is about unleashing more potential. Instead of focusing on people as potential risks, we should focus on their potential strengths, Chris said.

“To me this is really about helping America reach its full potential and living up to the high ideals we set forth at the creation of this country,” he said. “Without addressing the inequities created from the criminal justice system, there’s no way we can have a society where folks are fully free and have equal opportunity.”

Supreet Minhas (she/her) is a Senior Program Associate with Activating Change—a national nonprofit working to end victimization and incarceration of people with disabilities and Deaf people in the United States. Activating Change launched in 2022, but its work began in 2005 as a project of the Vera Institute of Justice. Activating Change launched as an independent nonprofit to increase the visibility of the justice issues people with disabilities and Deaf people face and to have a greater impact on ending those injustices. The organization is a Strategic Ally in the Safety and Justice Challenge.

“Criminal justice reform cannot take place equitably without accounting for the millions of people with disabilities ensnared in the system,” Supreet said. “Centering disability justice is essential to understanding and eliminating mass incarceration.”

Supreet helps organizations to understand how ableism and racism intersect. For example, 30-50% of people killed by police are people of color with disabilities. 40% of people in jail have at least one disability.

“The most vexing part of this work is continually being confronted with ableism and its pervasiveness in our society,” she said. “The Americans with Disabilities Act was passed 32 years ago but people with disabilities and Deaf people continue to be routinely denied access to accommodations like sign language interpretation.”

The criminal justice movement is decades behind in addressing ableism, especially in comparison to progress being made toward tackling sexism or racism, Supreet said. The omission of disability in the broader equity framework, has upheld and perpetuated structural barriers. People with disabilities are systematically excluded from having a part in crafting policies or making decisions—from being “at the table.” And there are myriad barriers for someone with a disability to even be at the table, from not being deemed worthy enough to warrant an invitation to the table itself being inaccessible. The impact of these challenges is borne out by the data on disability disparities, which shows that people with disabilities and Deaf people make up disproportionately high percentages of justice-involved individuals.

The “invisibilization” of people with disabilities has always been one of the most formidable challenges facing us, going all the way back to people with disabilities being excluded from ancient societies (e.g., leper colonies), then institutionalization in the modern era, and present-day mass incarceration. Most people do not want to talk or think about disability issues unless they are directly impacted—it’s a ‘problem’ for “others,” Supreet said.

“Even within the criminal justice reform field, the majority of organizations working to advance equity in the criminal legal system are not even considering disability justice in their approach, much less centering it,” Supreet said. “Disability is perceived as a complex, thorny issue best left to be worked on by disability-specific organizations in silos. However, until we all realize that justice and fairness for all cannot be achieved without intentionally considering people with disabilities and including them at policymaking tables, disability disparities will worsen, and we will have two separate, unequal tiers of justice.”

One of the biggest hurdles to improving outcomes for people with disabilities and Deaf people and achieving an equitable criminal legal system is that these two goals have been disconnected from one another, Supreet said. “The movements and organizations striving for these respective goals have been working in silos. This must change.”

Candace Coleman (she/her) is a Black disabled woman from the South Side of Chicago. As a Racial Justice Organizer at Access Living she works closely with disabled people affected by the justice system to organize around racial justice and disability. Candace’s most notable work involves organizing around mental and behavioral health emergency response. She played an integral in passing the Community Emergency Services and Supports Act in 2021—paving the way for Chicago’s 988 service. She continues to work diligently to implement non-police alternatives to emergency response in these situations.

Candace said a major area of her focus, right now, is the absence of accurate data about people with disabilities in the jail system.

“I’m encouraged by the work we’ve done over recent years to put people with lived experience at the center of decision-making, but if anything that has highlighted how little we did it in the past, and we’re really building the lane for people to participate,” she said. “Meanwhile, we’re doing that with very little data collection about people with disabilities who are in the system. If we don’t even have accurate numbers to reflect the scale of the issue, how can we move forward to help solve it?”

Recent focus on behavioral health and mental health issues has continued to marginalize other disabilities from the criminal justice reform conversation, Candace said.

“We’re not tracking people with cognitive disabilities, we’re not tracking people who are visually impaired, people who are Deaf, people who require physical accommodations and accessibility,” she said. “It’s just not been a priority to track such people. And without it being a priority, we can’t make progress.”

“We need to move towards supporting people as they come out of the system,” she said. “It means we need to identify people with disabilities who come into the system so that we can provide the programs and support they need when they come out of jail, or we fail.”

Jalyn Radziminski (they/she) is a Black and Japanese Disability activist from Indiana. Jalyn is the Communications Manager & Lived Experience Advocate at Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law and an Evening Student at Fordham School of Law. Jalyn builds coalitions to support the work of other peers with lived experiences of Jalyn also works on campaigns that promote community-based mental health supports.

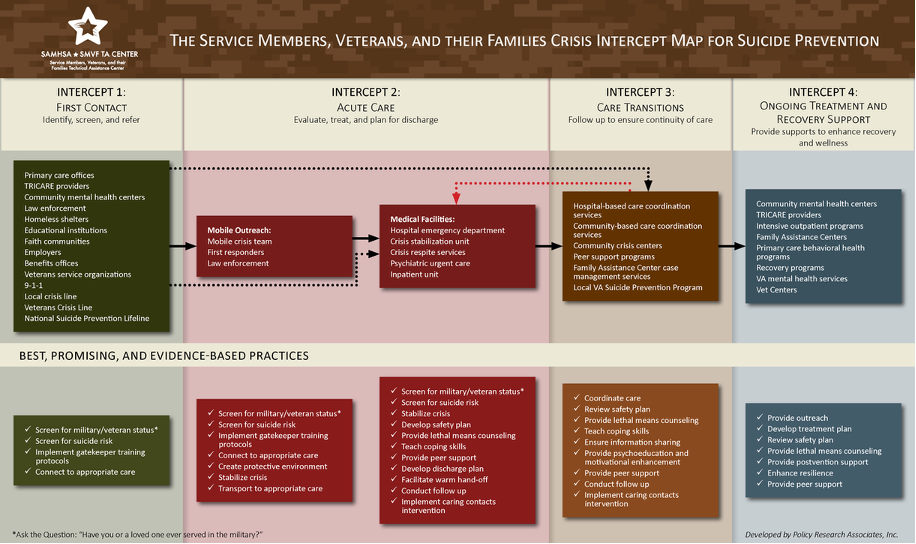

“We’re trying to reduce the chances of people going through involuntary commitment and police response to a mental health crisis,” Jalyn said. “A lot of grassroots leaders and legal advocates are starting to understand that the mental health system and the criminal legal system are intertwined. I’m working to keep people out of both.”

“One of the major challenges of the new 988 numbers around the country, is how they can lead to these undesired outcomes. People may call these sort of hotlines in distress, and before they know it, the police might show up at their door. People are scared that if they say the wrong thing, then the police will come,” they said. “It’s surprisingly easy for people to fall into a loophole of a police encounter and then before long, there’s involuntary commitment or incarceration”

Despite community-based models operating successfully since at least the 1970s, the majority of mental health research cites involuntary psychiatric-based treatment and response methods. There are many barriers for people of color with disabilities to have their work funded and published. The data from community-based perspectives is often lacking and this feeds into the lack of published research on community-based models of mental health treatment, Jalyn said.

“I’m working to push academia to bring these alternative models into the research field,” they said. “One of my proudest moments is recently receiving a competitive research grant for a joint-research project between the Bazelon Center, Mental Health America, and the University of Pittsburgh to help study the disparities of that research while uplifting peer voices.” Projects like these are just the start of a larger push to better collect and analyze data on community-based models and compare their success rates to the mainstream involuntary, incarceral responses.

“Investment is a major challenge, too,” they said. “A lot of the time policymakers think simple reform will fix some of the issues but you’ve got to invest in peer-led models. Underinvestment can lead to short-staffing, and there’s a domino effect.”

Jalyn cited the Kiva Center’s Karaya Peer Respite as a great example of successful peer-led respite program with a mobile team. They also pointed to the Promise Resource Center in North Carolina. “These home-like models give people somewhere to go where they can get rest and reflection when they’re experiencing emotional distress,” Jalyn said. “They support people through crisis to find healing.”

“The more we uplift peer networks and lived-experience-led approaches, and the more we push back in our voices from the policy to on-the-ground level, we’ll start to have better ways of preventing these issues from happening over and over again,” they said. “It’s long overdue to move away from these models and on to something new.”