Community Engagement Policing October 13, 2018

In 2020, Americans across the country joined in protest to demand an end to racial injustice and police violence. As more and more Americans begin to reconsider the role of law enforcement in our society, city leaders have a unique opportunity to re-envision their approach to strengthening community safety and wellbeing.

Sparked by a series of high-profile incidences of police violence against the Black community, the protests drew national attention to the outsize role of policing in many American cities. The number of police officers nationwide has ballooned over the past several decades, yielding only modest impacts on crime rates, at best. From resolving noise complaints to reversing overdoses, our society has come to rely on police officers to respond to a broad swath of issues beyond simply responding to crime. The expansion of policing has created disproportionate harm for Black Americans, who are unjustly subjected to higher rates of arrest, incarceration, and aggressive enforcement tactics. All too often, contact with the police can turn fatal. Police violence is now among the leading cause of death for Black men, one in 100 of whom will be killed by law enforcement in their lifetimes.

Now, building on years of work from grassroots campaigns and local advocates, the movement to shrink the footprint of the police is gaining momentum in communities nationwide. As the calls for change grow louder, local governments are increasingly looking to rethink their approach to public safety to better meet the needs of residents. A new Center for American Progress report—“Beyond Policing: Investing in Offices of Neighborhood Safety”—offers a roadmap for cities to sustainably shift toward a community-driven approach to public safety, starting by establishing a civilian Office of Neighborhood Safety (ONS).

An ONS serves as a hub for nonpunitive public safety solutions, which might include violence interruption, job readiness programs, civilian first responders, transformative mentoring, and others. Crucially, such offices are situated outside the justice system and staffed entirely by civilians, setting them apart from traditional public safety agencies. By establishing an ONS, local governments officials have a unique opportunity to ensure that data-driven community safety strategies receive the sustained financial and political support necessary to create meaningful impact. And by embedding nonpunitive approaches into the fabric of government, city leaders send a powerful message about the importance of these strategies – an important step towards changing the narrative around public safety.

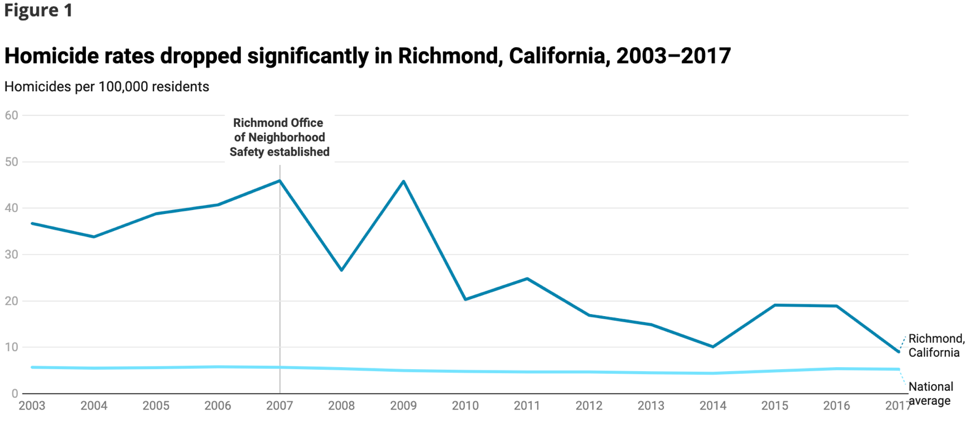

The ONS model was pioneered in Richmond, California, where community-driven strategies like the Peacemaker Fellowship have contributed to significant reductions in citywide homicide rates. When Richmond established its ONS in 2007, the city had the highest homicide rate in the state of California. That year, the city recorded 45.9 homicides per 100,000 people—eight times the national average. Ten years later, in 2017, the city’s homicide rate had fallen by 80 percent, to nine per 100,000.

As cities consider launching such offices, local leaders should think about the following:

- Creating a community-driven agenda: Cities should consider creating a permanent pathway for residents to engage with the ONS and shape the development and implementation of public safety policies. The city of New York, for example, is institutionalizing the community’s role in policymaking through NeighborhoodStat, an initiative operated by the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety. NeighborhoodStat is a joint problem-solving process that empowers residents of high-crime public housing developments to work directly with city agencies to craft a public safety agenda that is grounded in the community’s needs.

- Budgeting: Cities should make a sustained investment in their ONS, ideally through the municipal budgeting process. Some jurisdictions have established new taxes to create dedicated revenues streams for community-based interventions. Jurisdictions in which marijuana sales are legal may also consider earmarking a portion of tax revenue to support community safety initiatives. Other options for funding community-based safety interventions include limiting the growth of the police department’s budget, or shrinking it, and redirecting funds toward community safety priorities.

- Promoting accountability: ONSs should be held accountable for achieving meaningful improvements in public safety. City leadership must set clear and realistic outcomes and goals and then hold ONS leadership accountable for meeting these milestones over the specified period of time. City leaders should work with ONSs to set realistic public safety goals, using the evidence base from other jurisdictions as a guide.

- Creating flexibility: City officials should recognize that community-based interventions differ from traditional government programming, and the structure and function of the ONS should reflect this. Cities must consider creating flexibility for ONSs to operate outside the regulations that were developed to fit traditional government agencies. For example, an ONS must be permitted to recruit job candidates from outside the civil service sector, and to hire employees with justice system involvement.

- Engaging credible messengers: When preparing to launch an ONS, local leaders should consider how they want to engage credible messengers—community members who are able to connect with high-risk individuals based on their shared backgrounds and life experiences. Some cities have hired credible messengers directly into full-time employment with the municipal government, whereas others contract with nonprofit organizations to provide services in neighborhoods across the city. Regardless of model, cities should support the professionalization of credible messengers. Their work is difficult and potentially dangerous, and cities should invest in the professional development and support they need to succeed.

The ONS model represents a powerful tool for institutionalizing community-based interventions. By establishing an ONS, local leaders can take the first step toward shrinking the footprint of policing and making a meaningful investment in public safety beyond policing.