Community Engagement Pretrial Racial and Ethnic Disparities January 26, 2021

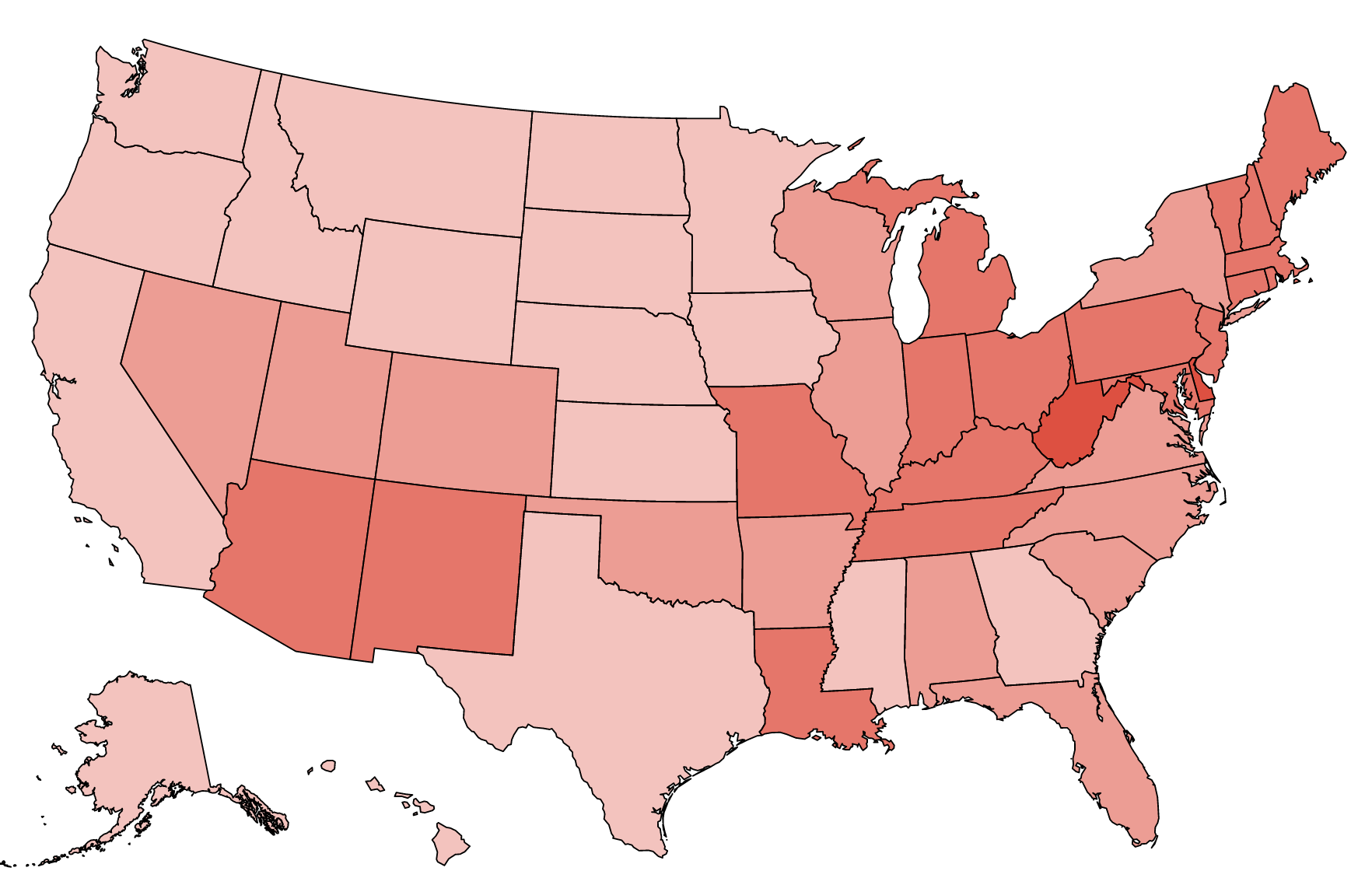

As technical assistance providers to the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, my colleagues and I have worked with several key sites across the country to embed racial equity as an integral part of addressing America’s over-reliance on jails, often through better community engagement, particularly in Black and brown communities.

Our work over the last three years has had some success, and we’re excited to build on it. And a key lesson has been to ask often, when we’re working with decision-makers: Who isn’t here in the room? Why not? And how can we bring them in?

Very often, in our long careers, my colleagues and I have found ourselves brought into rooms of criminal justice decisionmakers who do not look a great deal like the communities in which they’re working. It’s not always constructive to ask a room full of white people in suits to look around themselves and ask “who’s missing?” But there are constructive ways to bring more diversity into the system, and to start that conversation moving.

If a person who’s waiting on their court date were to come into that room of decisionmakers, they’re going to ask themselves: “Do I see people I can trust, to whom I can tell my story without judgment? Do I see people who’ll be supportive of me and help me with my family situation?”

People are fearful, and they don’t know what’s going to happen. When we talk about building trust in communities, we need to honor that fear, and try to understand it.

I started doing this work when the Rodney King incident happened in Los Angeles. I was working with the Department of Justice on its 15 member National Church Burning Response Team when President Bill Clinton was in the White House. We traveled around the U.S. to communities where houses of worship had burned. Being a part of that experience and my background in conflict management and resolution has afforded me a good sense of what people who are in vulnerable situations are feeling. There is a lack of trust for systems and players who are perceived to hold power and resources. In this instance my role as a conciliation specialist was to pave the way for federal officers from agencies like the Federal Bureau of Investigtion and the bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, along with local and state officers, to properly do investigations.

The unjust history and their personal stories are there when you go into communities. Understand: It’s just a lot. The stories that they hold. You need to pay attention to that, it’s not just coming in and saying “we want to work with you” and “we want to help.” When we talk about organizing, we talk about building that trust.

Using our dialogue to change approach, there are checklists we’ll work with, when we’re helping sites to build coalitions to tackle their issues: Does your coalition include people with different racial and ethnic backgrounds, different religious or philosophical views, and different political views? People with lived experience in the criminal justice system? Different ages? People with disabilities? Different professions? From different neighborhoods? People with different viewpoints on criminal justice? Different education levels? Folks with diverse gender identities and socioeconomic status?

Sometimes, it’s simply a question of prompting ourselves as decisionmakers to ask how we are showing up in our communities. What unconscious biases might be impacting our behaviors and decision-making?

As an African American – a Black woman, I have a vivid memory of being brought into a courtroom to observe as a judge was conducting pre-trial arraignment in a major city. Most of the defendants who came into the courtroom were Black or brown, and the judge referred to them by number, not by name. They were often asked if they could make bail, and many of them couldn’t. Then a young white defendant came in. She had been before the same judge, it turned out, although the judge still referred to her by her number. Still, she was sent straight to drug diversion. There was no question of her being asked about bail or staying in jail. I remember my own bias surfacing, and scoffing as I thought, “of course the young white woman is going to diversion.”

I don’t know the details of the young lady’s case. And it may well have been that the judge made the right call in sending her to diversion. The point is that for Black and brown people, our knowledge of the criminal justice system is shaped in the context of the history of our communities, and the history of the United States. When we see something like what I saw, we don’t always have time to think about the ins-and-outs. There’s a reaction to something we feel we’ve seen before.

The incident stuck with me, and I often talk about it with white criminal justice decisionmakers when we talk about how they show up in their communities, and the impact that they’re having.

There’s also a researched and proven tendency that in communities where there are more Black and brown folks, white decisionmakers can tend to micromanage, a little more, than they might do if they are working in communities where more people look like they do.

When it comes to the Safety and Justice Challenge, the sites that have been most successful in tackling racial inequity in the system have tackled it head-on, naming it as an issue and recognizing the role that power dynamics play in addressing it.

Some justice system leaders show up to our trainings curiously willing to ask the hard questions about why so many Black and brown people continue to show up in our jail system and why so many Black and brown people are being arrested.

Such sites have hired Black and brown community engagement managers who know the communities in which they work, and understand what it looks like to build trust, and what that means. These people have the voice of the communities in which they’re working. And that’s where the push for racial equity really starts to move things in the right direction.