Courts COVID Pretrial December 16, 2020

Necessity is the mother of invention, and cities and counties participating in the Safety and Justice Challenge have learned a great deal from measures taken to save lives during COVID-19. What’s more, many of these lessons will prove valuable in the years ahead, both as the world continues to fight the virus and afterwards.

With strategies to reduce jail populations already in place and key decision-makers already at the table working together, many SJC sites were better positioned to respond to the crisis than jurisdictions not already engaged in these efforts. For example, sites deployed new or existing Population Review Teams to identify those who could be quickly and safely released to prevent spread of COVID-19 in jails and the broader community. The stakeholder collaboration and evidence-based strategies already in place through the SJC allowed many sites a head start in mitigating the spread of COVID-19.

Without exception, all the cities and counties involved in the Safety and Justice Challenge managed to substantially reduce their jail populations during the pandemic, without jeopardizing public safety. In many cases, average daily jail populations reached levels lower than at any point in the last quarter century. For example, Buncombe County in North Carolina reduced its jail population by 42% at its lowest point, San Francisco County, California, by 35% at its lowest point, and Allegheny County in Pennsylvania by more than 30% at its lowest point.

Without exception, all the cities and counties involved in the Safety and Justice Challenge managed to substantially reduce their jail populations during the pandemic, without jeopardizing public safety.

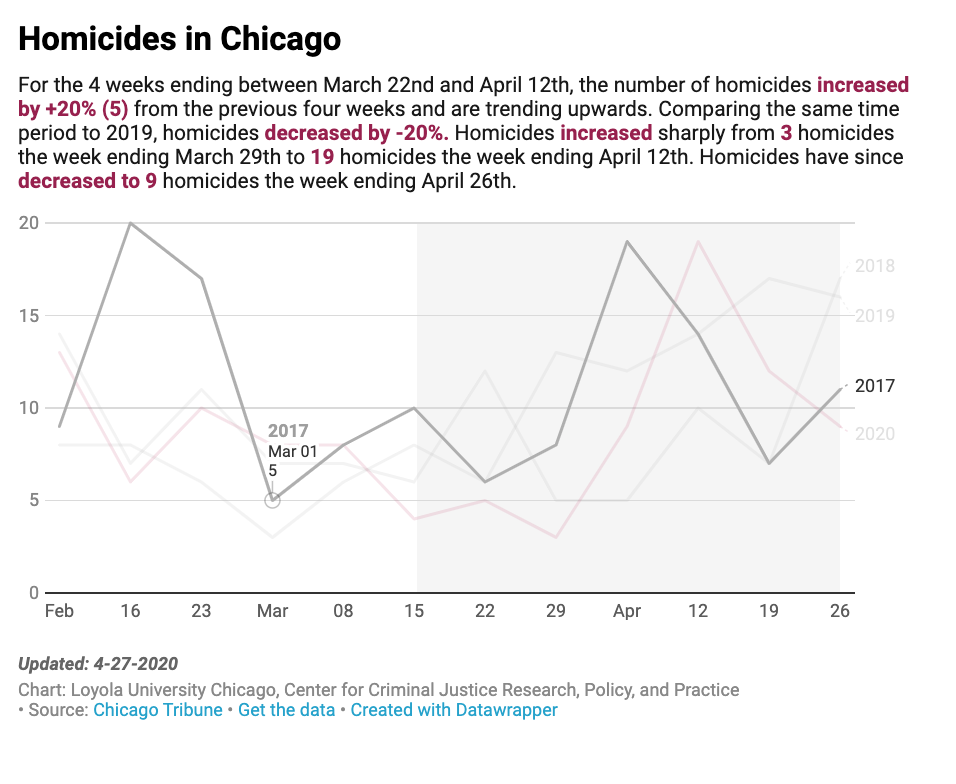

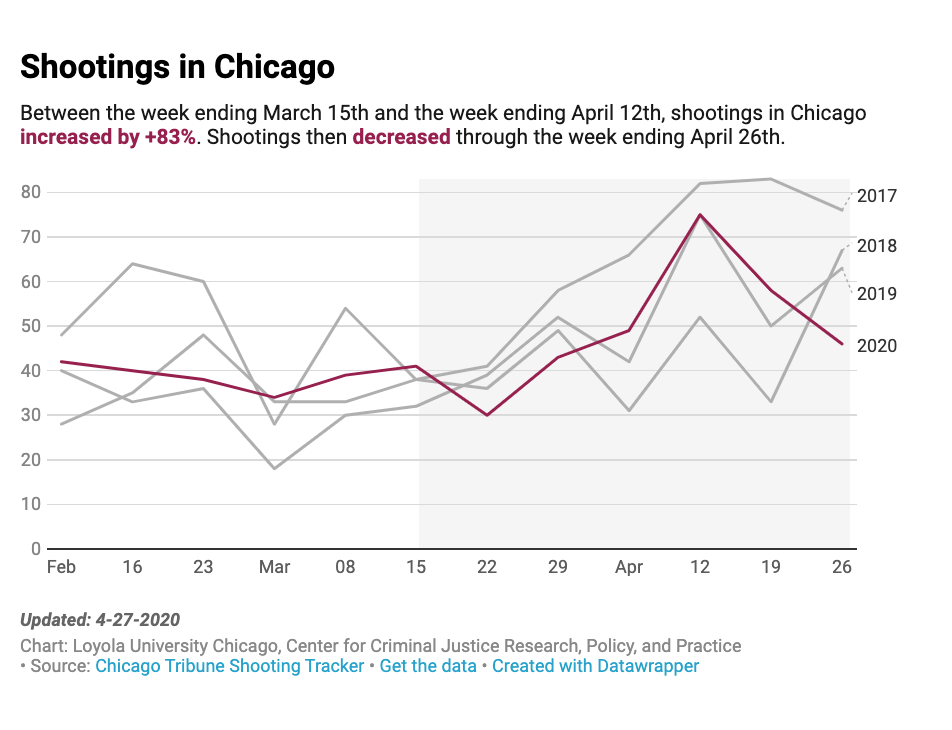

However, local justice systems had varying levels of success in tackling the virus despite testing and control measures. East Baton Rouge Parish in Louisiana, for example, saw only one positive COVID-19 test at its pretrial detention facility. In Buncombe County, there have been no COVID-19 infections in the jail, largely due to a strict initial quarantine program and the ability to keep all incarcerated people in single cells (one person arrived at the jail with COVID-19 but did not pass the virus to others). Among detainees in Cook County, Illinois, a total of 1,096 detainees have tested positive as of December 11, 2020. Many people booked into the jail are coming in with the virus, rather than catching it inside the jail – further demonstrating that reducing jail bookings is critical to preventing spread of the virus.

How did cities and counties in the Safety and Justice Challenge respond to COVID-19? And what have we learned?

1. Reducing Arrests and Jail Bookings, Increasing Releases Helped

In cities and counties participating in the Safety and Justice Challenge across the country, justice system actors worked together to reduce the number of people being booked into jails, and to prioritize case review for people in custody so that they could be released, where possible. They also worked together to prioritize release of people with vulnerable health conditions, who could safely be released pretrial or while serving their sentences. There has been collaboration with police to issue summonses in lieu of arresting people on nonviolent misdemeanor charges, when safe to do so. Many cities and counties even suspended arrests for some felonies and for certain warrants which could be resolved in the field. In Clark County, Nevada, prosecutors aggressively screened cases and quickly diverted or dismissed those that were not likely to go forward or that didn’t present a threat to public safety.

In Multnomah County, Oregon, more people were released on their own recognizance. In New Orleans, the JFA Institute found that defendants released from custody had very high overall success rates — nearly 80% have no “failure to appear” or re-arrest. And 92% of defendants in the lowest risk category attended all required court appearances. In Allegheny County, three-month rates for people reentering the system who had been released at the start of COVID-19 were slightly lower than comparable three-month reentry rates of people released from jail during the same time period in 2019.

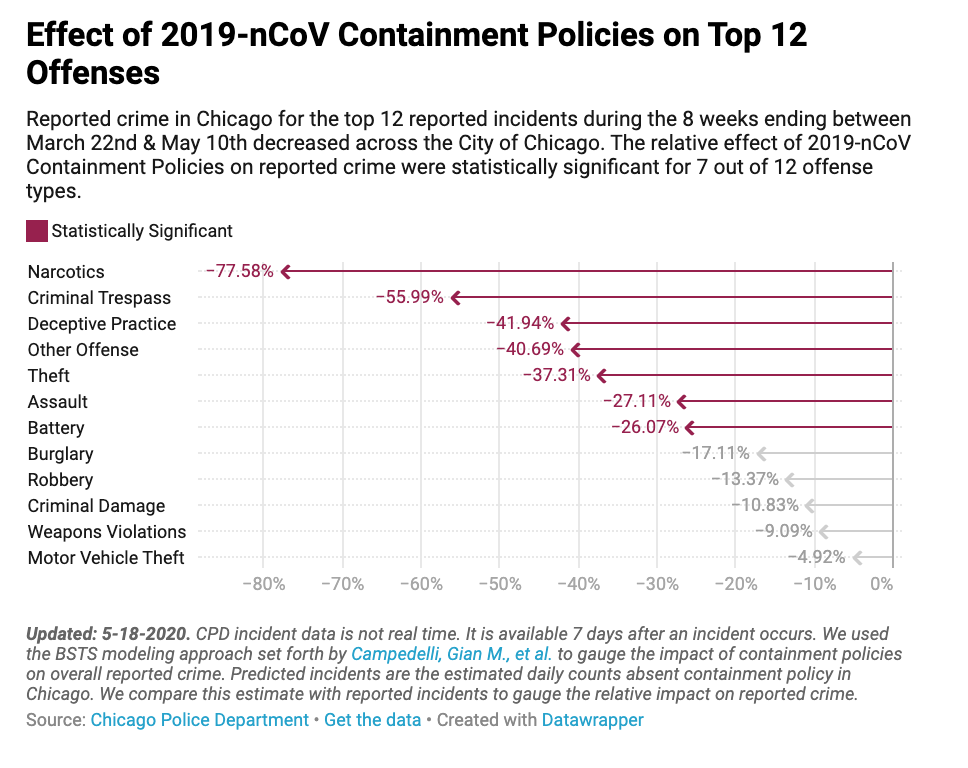

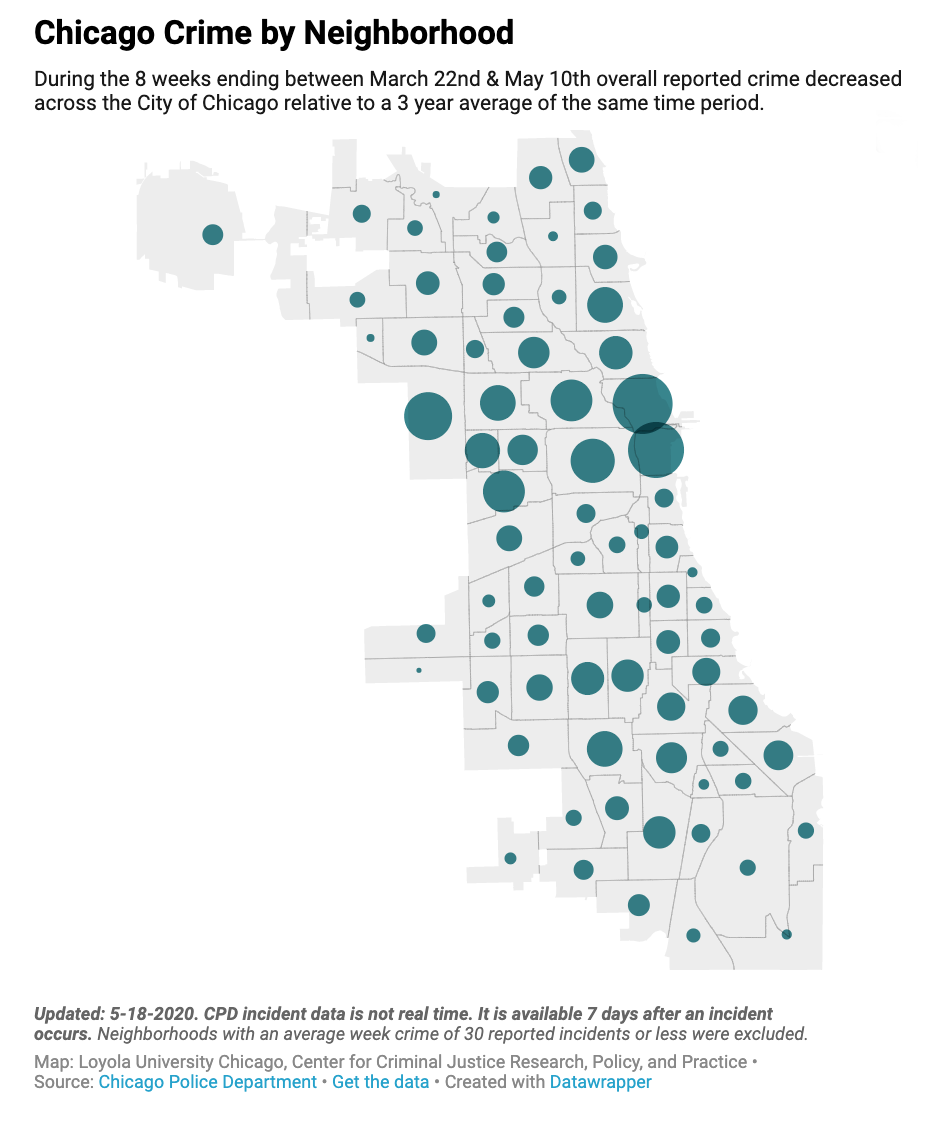

In Minnehaha County, South Dakota, justice system actors achieved a 53% reduction in arrests and jail bookings in March 2020, compared to the previous month. They attributed it to increased use of cite and release practices, and to setting lower bonds and operating a lower fine schedule. New Orleans Police Department reduced arrests for non-violent charges by 63% compared to the same period in 2019, with overall arrests down 59%. Lake County, Illinois, reduced arrests by 27%. The Baton Rouge Police Department expanded its cite and release policy to include traffic offenses, nonviolent misdemeanors and low-level felony charges.

2. Changes in Bail Protocols Have Proven Successful in Safely Reducing Jail Populations

Cities and counties across the country made substantial changes to their bail protocols during COVID-19. For example, The Los Angeles County Sheriff, with the support of the Public Defender and other agencies, instituted a policy of releasing anyone with $50,000 bail or less, in specified cases. The State Superior Court also reset bail amounts under the existing bail schedule to $0 bail for designated offenses. While the changes expired as part of the state’s emergency bail order in June 2020, Los Angeles County has extended this order locally to remain in place as part of the ongoing pandemic response. Clark County, Nevada shifted the burden of proof in bail hearings, requiring prosecutors to show why a defendant must be kept in custody. St. Louis County connected people in jail who couldn’t afford their bail with The Bail Project to help secure their release.

Despite some naysayers, we know this type of bail reform does not put the public at greater risk. New academic analysis shows Chicago area bail reform efforts since 2017 have not increased new criminal activity. Creative and evidence-based steps like these paved the way for other jurisdictions to follow suit and respond to the pandemic.

3. Technological Tools Kept Systems Operating

Just as new apps like Zoom, Microsoft Teams and Slack have changed working life during the pandemic, technological innovations have transformed justice systems operations in the era of social distancing. Many sites began holding video and telephone appearances in their courtrooms, rather than in-person hearings. In Palm Beach County, Florida, a new text message court reminder system reduced failure to appear rates from 8% to 3%. St. Louis County bought tablets for the jail so that attorneys could conduct video meetings with their clients more easily, expanding on the Public Defender’s existing initiative to represent people at their first court appearance. Probation and Parole Departments also instituted virtual check-ins that aided in reduced revocations back to custody.

4. A Focus on Behavioral Health Improved Reentry Success

Cities and counties have continued to invest in keeping people from being rearrested or being arrested in the first place. They have provided housing, food, medication, transportation, and other service referrals for people being released from jail so that they don’t cycle back into the system. Recognizing the importance of meeting these social services—which can be a challenge, particularly in larger jurisdictions—sites are investing more deeply in reentry resources. Palm Beach County, for example, has provided permanent supportive housing with wraparound services for 12 people experiencing homelessness with behavioral health challenges as part of a Safety and Justice Challenge-funded pilot program. In the two-year period before they were housed, these individuals had collectively been arrested 64 times and spent 704 days in jail.

5. Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities Will Require Renewed Commitment

COVID-19 further exposed racial inequities in America’s jails. In many cases, we saw racial disparities increase across participating cities and counties as a larger percentage of white people were released from jail than Black people. In Palm Beach County, Florida, for example, white people were twice as likely to be released compared to Black people from February to July 2020. In Buncombe County, the portion of jail population that is Black increased steadily from 23% in February to a high in July of 33%, compared to a county-wide population rate of around 8%.

How We Can Build on Our Momentum

Several cities and counties plan to build on changes they have made during COVID-19 to keep any substantial rebound to a minimum and continue releasing more people with low-level charges. For example, Los Angeles County plans to close its Men’s Central Jail within a year, reducing more than 3,000 beds from its pretrial capacity. San Francisco has already closed one of its jails. Meanwhile, Clark County, Nevada plans to keep its emergency measures in place until July 2021 and use the data collected to move forward from there.

—Wendy Ware is the President of the JFA Institute, which works in partnership to evaluate criminal justice practices and design research-based policy solutions.