COVID Crime Data Analysis Jail Populations December 18, 2024

Jails book and confine more than 10 million people every year in the United States. People incarcerated in jails can experience overcrowding, lack of resources, exposure to violence, and deteriorating physical and mental health.

In response to these harsh conditions and impacts on individuals, practitioners and policymakers have pushed to reduce the size of US jails. As part of this national movement to rethink jails, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation founded the Safety and Justice Challenge to provide support to local communities to tackle the misuse and overuse of jails. With financial and technical assistance support from MacArthur, over 50 cities and counties have implemented innovative strategies to reduce their local jail populations by releasing more individuals on pretrial release and reconsidering the use of jail for new bookings.

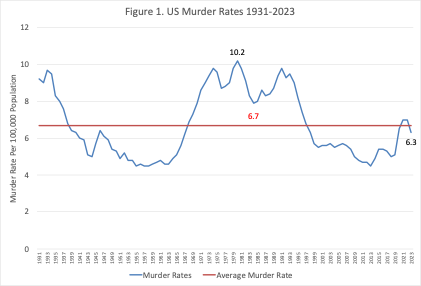

However, the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020 forced cities and counties participating in SJC to reduce their jail populations even more to meet social distancing recommendations. Since COVID-19, data from SJC communities analyzed by the CUNY Institute for State and Local Governments (ISLG) consistently show that decreasing the jail population does not lead to violent crime. Additionally, across SJC cities and counties, most individuals released pretrial were not booked for a new crime, and it was even more rare for an individual to be re-booked for a violent offense. Combined, the data from SJC communities suggests reducing the size of the jails is not only possible but does not lead to a rise in crime broadly or a rise in violent crime, specifically.

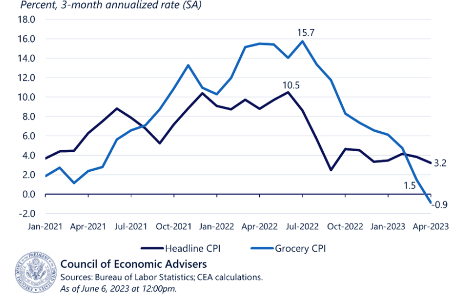

This is especially true for Multnomah County, Oregon, which had remarkable declines in their jail population during COVID without a rise in violent crime. Capitalizing on existing SJC relationships, Multnomah County stakeholders implemented some new strategies but mostly relied on expanding the eligibility of existing SJC reforms to quickly reduce their jail population. At the same time, the county experienced decriminalization of drug use and 100 days of social unrest in protest of police brutality and systemic racism which created the destruction of several buildings and businesses. Combined, the decriminalization of drugs and protests increased the visibility of drug use, houselessness, and created a general sense of lawlessness across the county even though crime or violence did not increase. Now, four years after COVID-19 began and two years after of the passage of the decriminalization of drugs, Multnomah County residents are critical of criminal justice reform and pushing for standard criminal justice responses, like the reliance on jail.

A new research study produced by Justice System Partners delved into the experience and data in Multnomah County and made the following findings:

- The Value of the SCJ during COVID-19. Because Multnomah County was already working with SJC when COVID hit, staff had all the infrastructure in place to safely reduce their jail population. The county’s participation in SJC laid the groundwork and framework for stakeholders to meet and collaborate quickly. Although some new approaches were implemented, the county mostly expanded the eligibility of pretrial reforms they had previously implemented as part of SJC. These strategies include citation-in-lieu of arrest and booking; reducing jail admissions for community supervision violations; limiting warrants for recorded court absences; and expediting jail releases with manual review. Using various strategies, county stakeholders reduced the number of bookings throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, and specifically experienced a steady decline in jail bookings across each of the subsequent four time periods.

- Reaffirming evidence on violent crime and using jails effectively. Reducing the reliance on jails did not lead to an escalation of jail bookings for violence broadly. Nor did it lead to an escalation of jail bookings for violence by individuals with a history of violent charges. The individual demographic composition of the jail remained relatively the same throughout the study period. However, the composition of the charges booked into jail changed significantly. Overall, the jail experienced a lower proportion of bookings for low-level and non-violent charges, demonstrating that during the two years following the start of the pandemic in March 2020, stakeholders relied on the jail for booking more serious charges. Bookings for violent charges did not increase during the pandemic, demonstrating that reducing bookings for low-level charges does not lead to an increase in violent charges. The composition of jail bookings shifted during the period of social unrest in the summer and fall of 2020, with a greater proportion of jail bookings associated with behavioral charges (such as disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, and harassment, among others). The jail held fewer people overall and fewer numbers of individuals were booked with a violent offense. However, what was booked was more often for a violent offense. Therefore, the proportion of violence charges in the jail increased, but not necessarily the number of violent charges. This suggests the county began relying on jail predominately for violent offenses charges – a more effective use of its jail.

- Perceptions of safety extend beyond classic definitions of violence. During the study period, community and justice system staff members reported a decrease in perceptions of safety, largely from visibility of drug use and social disorder. Community stakeholders discussed their perceptions of safety differently than justice system staff, echoing earlier Safety and Justice Challenge research on the multifaceted concepts of “safety.” This suggests system staff stakeholders should aim to “frame conversations around community safety instead of public safety.” Perception of public safety is less about classic definitions of violence and more about the discomfort with physical and social disorder. Community members often discussed perception of seeing or experiencing more “violence” during COVID-19, but actually described physical and social disorder including property damage and drug use. In the summer of 2020, community members protested police brutality and the role of the justice system in communities following the murder of George Floyd. Interviews with community members indicate that there is a need for conversations about the term violence, including which individuals and what charges should be characterized as violent. As a field, we must grapple with how people who commit violence and systems that are violent may be interconnected.

- Staff wellness matters for sustainability of reform. COVID-19 brought an emphasis and renewed interest in physical and emotional well-being and health. As we work to heal communities impacted by the justice system, we must also consider the impacts of the system on staff, too. Staff experienced significant workplace trauma from social unrest and still showed compassion for the need to reduce reliance on jails. Staff who experienced harms are still healing yet responsible for sustaining the work. There are significant challenges with tasking the people who experienced workplace trauma to champion reforms without acknowledgment or space for healing.

The experiences and data from Multnomah County during this period serve as valuable guiding principles for other communities looking to navigate the complex terrain of justice reform with equity, efficiency, and humanity.