Community Engagement Crime Interagency Collaboration Victims November 3, 2023

Bria Gillum, Senior Program Officer, Criminal Justice for the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and Aswad Thomas, Vice President of the Alliance for Safety and Justice (ASJ), appeared at The Atlantic Festival 2023 in Washington, D.C., in a talk entitled “How to Invest in Safety and Well-Being.” It was part of a session underwritten by the MacArthur Foundation on criminal justice reform.

Bria interviewed Aswad, who survived a robbery attempt that left him with two life-altering gunshot wounds, about his experience as a survivor of violence, and his journey to embrace the Trauma Recovery Center (TRC) model of addressing the needs of crime survivors, who often face the biggest barriers to accessing healing services.

After Aswad left the hospital with his gunshot wounds, there were no support services, or even information about where to look.

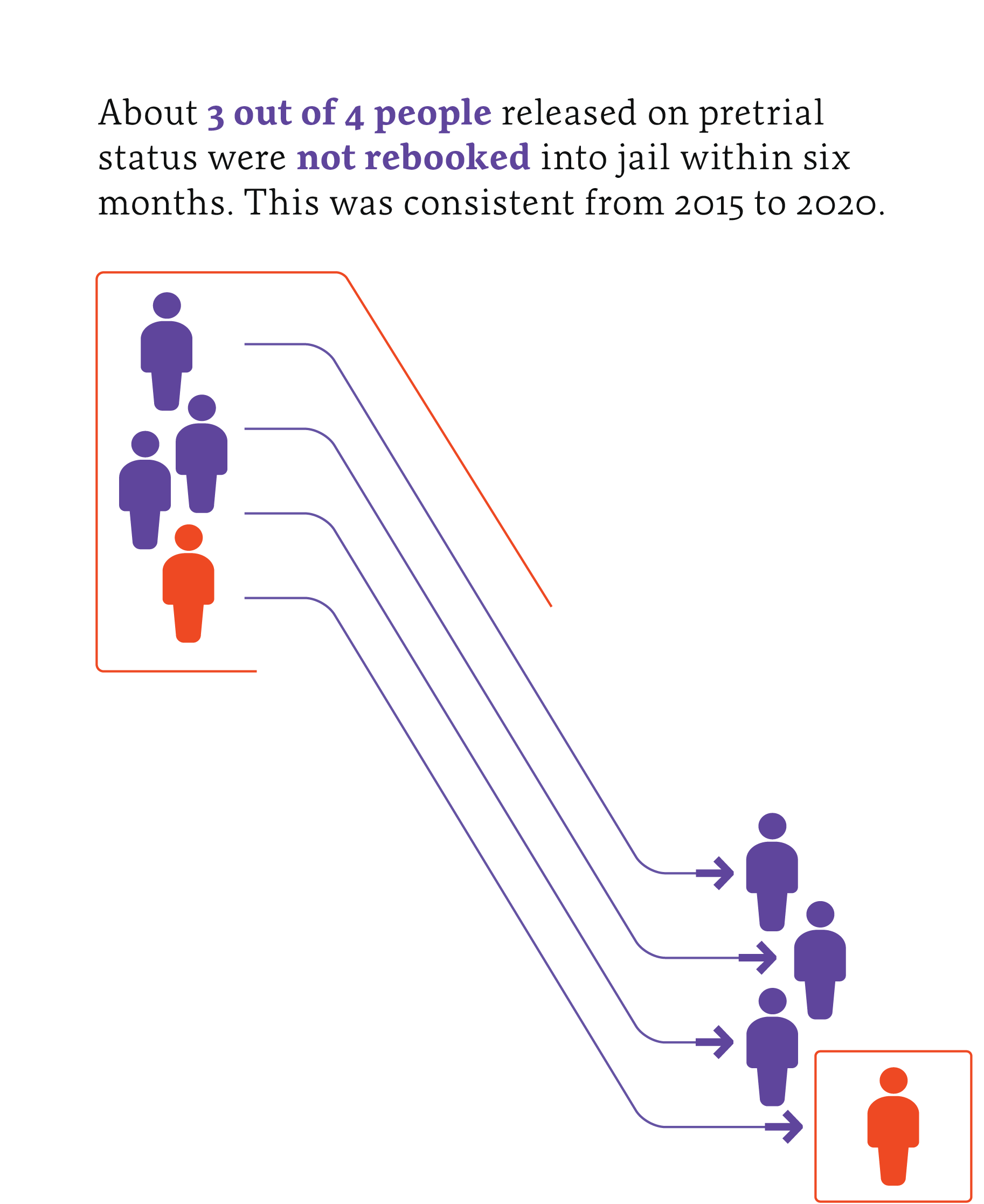

“My story might sound unique, but it’s not unique at all,” he said at the conference. “In this country, three million people are crime victims every year, but only nine percent of people get access to victim services.”

Thomas began organizing crime victims and advocating for victims’ rights, and today he is working to expand the ASJ’s national network of crime survivors to elevate their voices in criminal justice reform.

“When you think about the criminal justice system, the voices of crime victims like me have never been at the center of criminal justice policies,” he said. “One thing that we are trying to do is to elevate this new victims’ rights movement, this is calling for new safety solutions to help stop the cycle of violence.”

In addressing this need for advocacy, services, and resources, Aswad spoke about his organization’s TRC model as a “one-stop shop that provides you with all of the recovery services that you need, without all of the red tape.” The first center was developed at San Francisco General Hospital in 2001. Today, there are 52 TRCs in the United States.

He said community is at the heart of what ASJ does. “What we do is we build community,” Aswad said. “We build community with survivors, providing peer-to-peer support. We build community with law enforcement, with advocates, with legislators, and we build that community so that we can start having conversations around our public safety policies.”

Aswad shared some of ASJ’s accomplishments. “In the past 10 years, we passed about 91 criminal justice and public safety reforms across the country. We’ve changed victim compensation programs in about ten states. We’re helping to provide more protections for victims to be safe from employment protections and housing and protections.”

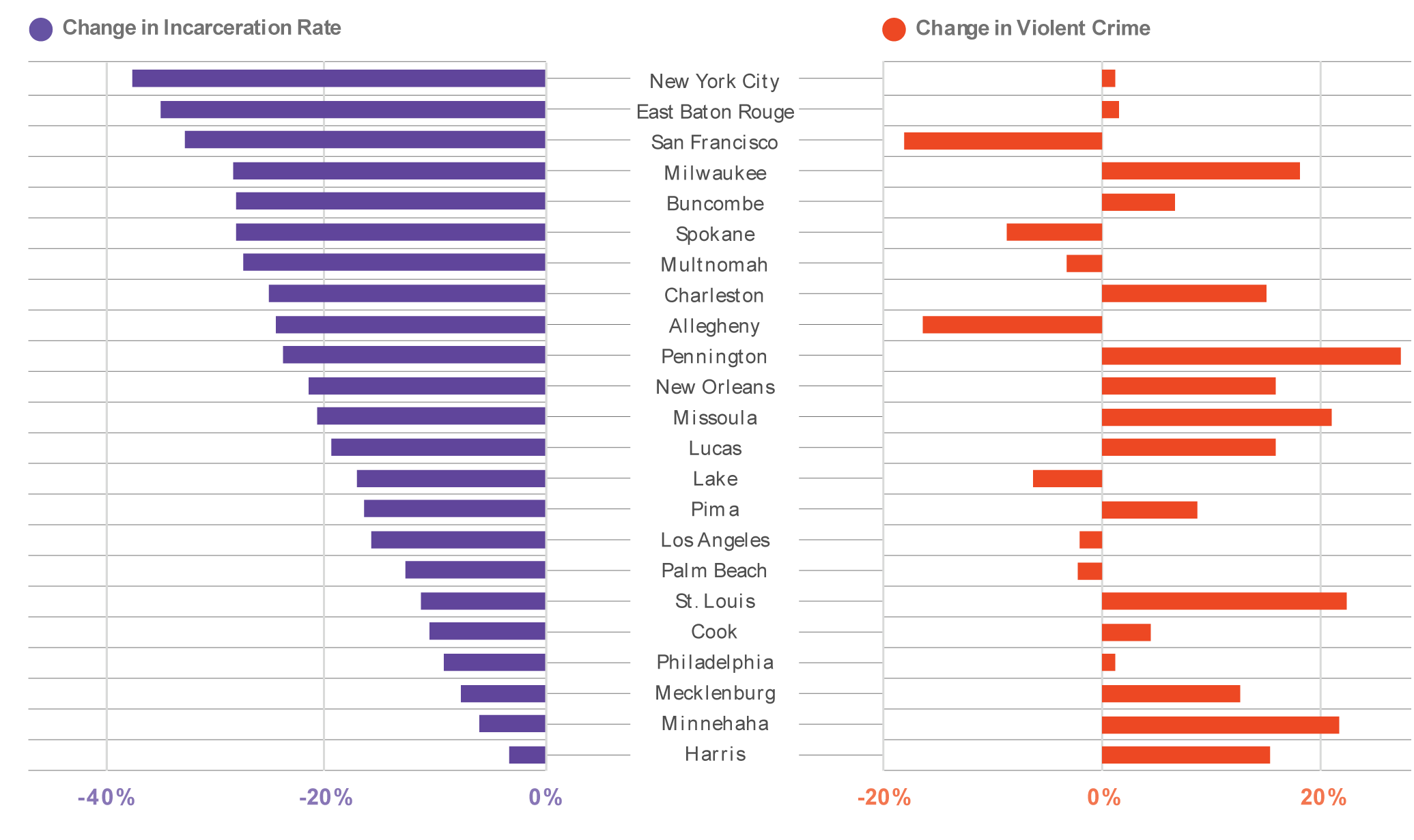

Another area of advocacy for ASJ is criminal justice reform. “Across this country, crime victims are now organizing to change criminal justice policies,” he said. “Past reforms have reduced incarceration and helped to incentivize more rehabilitation for folks who have caused harm. But also working on reforms to remove the barriers for people coming out of the justice system and back into our communities. We also passed laws, so [that crime victims can] access housing, jobs, education, things that help promote stability. Those are the things that help keep communities safe as well.”

In response to a question from Bria about what it means to be safe in your community, Aswad asked the audience to close their eyes and think about where they feel most safe.

“Is it a garden? Is it at church? Is it with family? Think about where you feel most safe. The majority of us in this room, I don’t think we say more police, or that we feel safe with more prisons. We feel more safe in community with each other. So that’s what we need to invest in, more Trauma Recovery Centers, more mental health programs, more solutions to help stop the cycle. That’s how we actually get to true safety in this country.”

You can watch the full conversation on YouTube.