Human Toll of Jail Jail Populations Victims Women in Jail August 3, 2023

One in four women experience domestic violence in their lifetime. But three in four women who have been, or are, incarcerated have experienced it. Despite these disparately high rates among incarcerated women, jails too often lack organized domestic violence-specific services for women. Very few jails have programs to address women’s needs related to abuse and trauma. It is time to change that because more research shows providing such services is a good idea. They can help increase the success of reentry services and improve well-being. And that is an important part of efforts to reduce jail populations across the country.

Peer-support groups are the focus of a new report co-authored by survivors. It is a project of the National Center for Victims of Crime with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge. Along with our panel of experts with lived experience, we convened a listening session to discuss how to create domestic violence peer-support groups in jails. The experts from this working group identified five principles to guide the development of domestic violence peer-support groups for women who are incarcerated. This is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point for engagement and implementation in institutions. We are hopeful that communities will want to partner with us to embed these principles.

Principle 1: The jail intake process should screen for whether a woman is a domestic violence survivor.

The intake process for women who are incarcerated should include an assessment to detect past domestic violence victimization, and jails should utilize gender-responsive assessment tools for this. Still, women who are incarcerated may not be ready to fully disclose their histories of domestic violence victimization when they arrive at a facility. Jails, therefore, should offer continuous opportunities for women to disclose information about their past.

Principle 2: Implement comprehensive and easily accessible compensation to peer domestic violence guides for their work.

It is vital that women serving as domestic violence peer guides are compensated, financially or otherwise, for their service. Women should be compensated regardless of whether they serve as peer guides during or after their incarceration. Furthermore, work as a domestic violence peer guide while incarcerated, at a minimum, should constitute an internship with a partnering domestic violence program and qualify as requisite experience for a paid position with the organization upon release. Building relationships with external domestic violence organizations can also help institutions strengthen their policies around working with women who are survivors of domestic violence.

Principle 3: Supportive partnership and collaboration between peer guides and external domestic violence programs is needed.

In addition to bringing domestic violence programming into jails, community-based domestic violence providers should train incarcerated victims and survivors to serve as peer guides. Community-based domestic violence programs should hire formerly incarcerated domestic violence survivors to work with domestic violence peer-support groups in jails and ensure that peer-support specialists receive just compensation. This duality of lived experience is necessary for peer guides to fully understand the traumas that have occurred before, during, and even after incarceration, and allows the guides to provide stronger and more relevant support for domestic violence victims who are incarcerated.

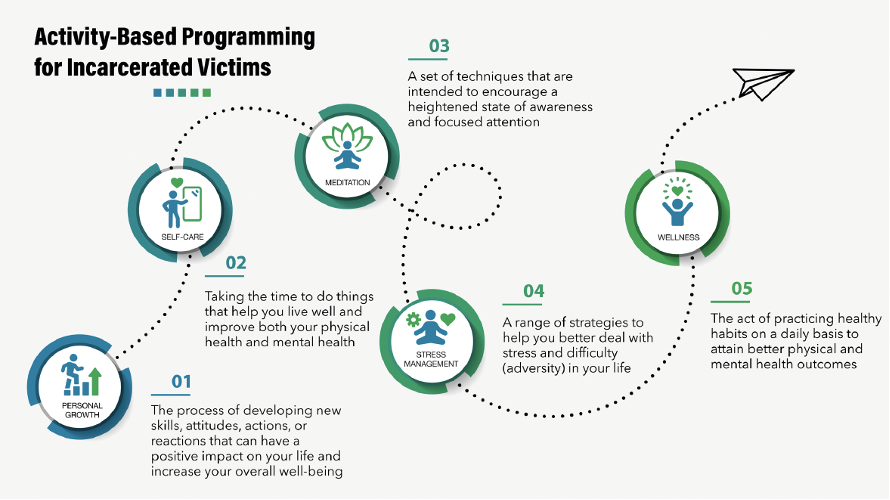

Principle 4: Ensure access to holistic care to treat the whole person.

Domestic violence peer-support programs in jails should engage holistically with incarcerated victims and survivors. Trauma is an emotional response to an intense event that threatens or causes harm. It is often the result of an overwhelming amount of stress that exceeds one’s ability to cope with the emotions involved with that experience. Educating incarcerated victims and survivors about trauma can help women realize that they are recovering from a serious stressor and learn more about their own stress responses and coping strategies, allowing them to build a sense of control over those responses. Trauma education can also minimize self-blame and build community among victims and survivors through a better understanding of their shared experiences.

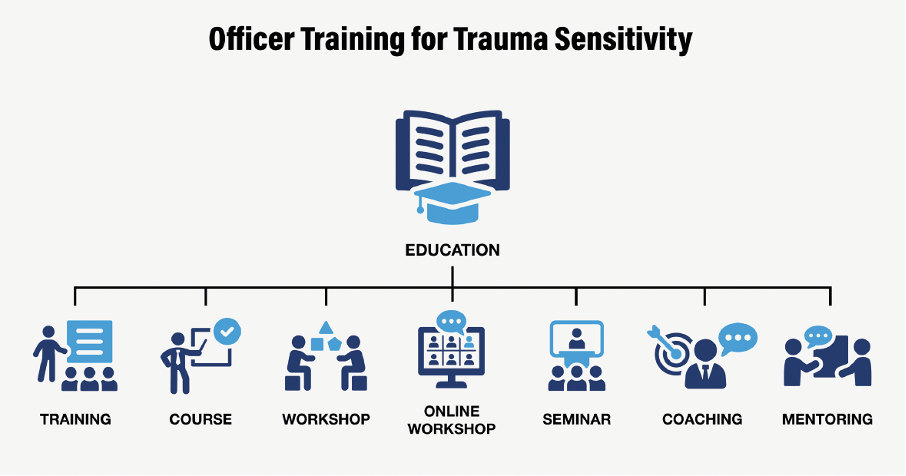

Principle 5: Correctional officers (CO) who transport women to and oversee domestic violence peer-support groups should be trauma-informed and trained on the dynamics of domestic violence.

The majority of individuals who interface with the criminal justice system, including jails, have been exposed to traumatic events, like domestic violence. However, institutional confinement, like jail, is not intended to house victims and often does not acknowledge or recognize that individuals involved in the criminal justice system are often victims before they committed their offense. Instead, incarceration is another traumatic event. Being locked in a cell is one of the most horrific, stressful experiences a person can endure. The act of locking another human being in a cell is also traumatic and potentially dangerous to the correctional staff. Incarcerated people and correctional staff alike are traumatized, forcing them to react to the world around them from a position of fear, making them more likely to respond with aggression. The trauma shared by staff and people who are incarcerated exists in a constant feedback loop in which no one feels safe.

Given the prevalence of preexisting victimization and ongoing trauma, especially in women who are incarcerated, jails need to embrace a trauma-informed approach and culture. A key part of creating this kind of environment is providing ongoing training to ensure that correctional officers understand the impact and prevalence of trauma and its pervasive effects on the brain and body, as well as the specific dynamics of domestic violence. Doing so can help to break the cycle of trauma for both women who are incarcerated and the staff who work with them.

The report would not have been possible without the expertise of our co-authors, Tanisha Murden and Rylinda Rhodes. We would like to thank them for sharing their knowledge, ideas, and experiences, as well as helping us create a more healing space for all survivors. We hope communities will find the recommendations in the report useful and explore implementing them in their policies. Just because someone is incarcerated does not mean they are not also victims of crime. In the case of domestic violence survivors, often the very actions that resulted in someone’s incarceration could have stemmed from self-defense or another means of escaping an abusive situation. It is incumbent on us, as a society, to support victims of crime in all circumstances.