Report

Data Analysis Jail Costs Jail Populations December 15, 2015

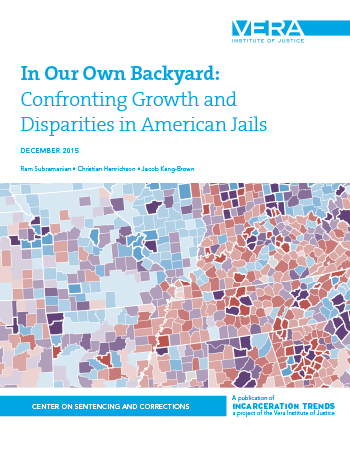

In Our Own Backyard: Confronting Growth and Disparities in American Jails

Although jails are the “front door” to mass incarceration, there is not enough data for justice system stakeholders and others to understand how their jail is being used and how it compares with others. To address this issue, Vera researchers developed a data tool that includes the jail population and jail incarceration rate for every U.S. county that uses a local jail. Researchers merged jail data from two federal data collections—the Bureau of Justice Statistics Annual Survey of Jails and Census of Jails—and incorporated demographic data from the U.S. Census. The data revealed that, since 1970, the number of people held in jail has increased from 157,000 to 690,000 in 2014—a more than four-fold increase nationwide, with growth rates highest in the smallest counties. This data also reveals wide variation in incarceration rates and racial disparities among jurisdictions of similar size and thus underlines an essential point: The number of people in jail is largely the result of choices made by policymakers and others in the justice system. The Incarceration Trends tool provides any jurisdiction with the appetite for change the opportunity to better understand its history of jail use and measure its progress toward decarceration.