Data Analysis Jail Populations Women in Jail March 27, 2024

Data is a key part of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, in its efforts to reduce local jail populations across the country. Likewise, a new data-based report by the Prison Policy Initiative highlights a stark reality: Women are disproportionately incarcerated in jails across the country.

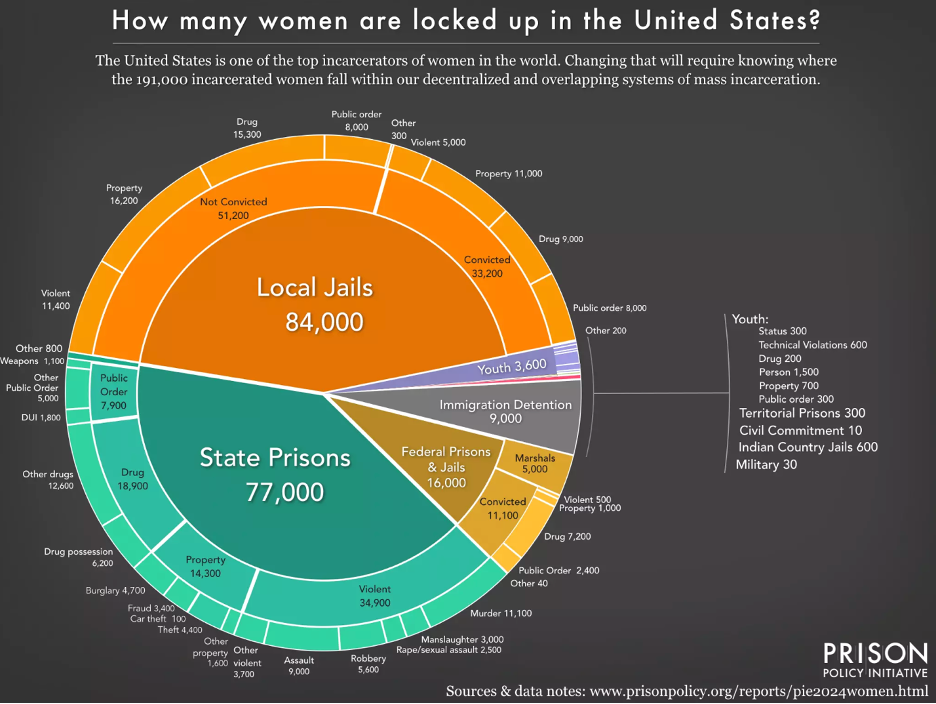

In stark contrast to the total incarcerated population, where state prison systems hold twice as many people as are held in jails, more incarcerated women are in jails than state prisons. The outsize role of jails has serious cascading consequences for incarcerated women and their families.

Gender-based data is inconsistent throughout America’s jail systems, not least because the data on women has long been obscured by the larger scale of men’s incarceration. Frustratingly, it is difficult to track changes in women’s incarceration over time because we are forced to rely on the limited sources available.

Nevertheless, the data that are available show us some trends. For example, we know that a staggering number of women who are incarcerated are not convicted. More than 60 percent of women in jails under local control have not yet been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial. And the number of women in local jails—84,000—only scratches the surface of the number of women—2 million—who go through the doors of local jails each year.

When law enforcement locks women up, even for a few days, it can have an outsized impact on their lives. Many women who are incarcerated may be working low-income jobs or serving as caregivers for their children. 80 percent of women in jails are mothers, and most of them are primary caretakers of their children. Thus children are particularly susceptible to the domino effect of burdens placed on incarcerated women.

A short jail stay can mean women lose custody of their children and their housing. Many women who end up in jail are survivors of domestic abuse, so jailing them compounds deeper injustices. Many survivors of domestic and sexual abuse have also been incarcerated for violent crimes that occurred in response to gendered violence and abuse, so excluding them from many criminal justice reforms based on offense categories such as “violent” crimes makes little sense.

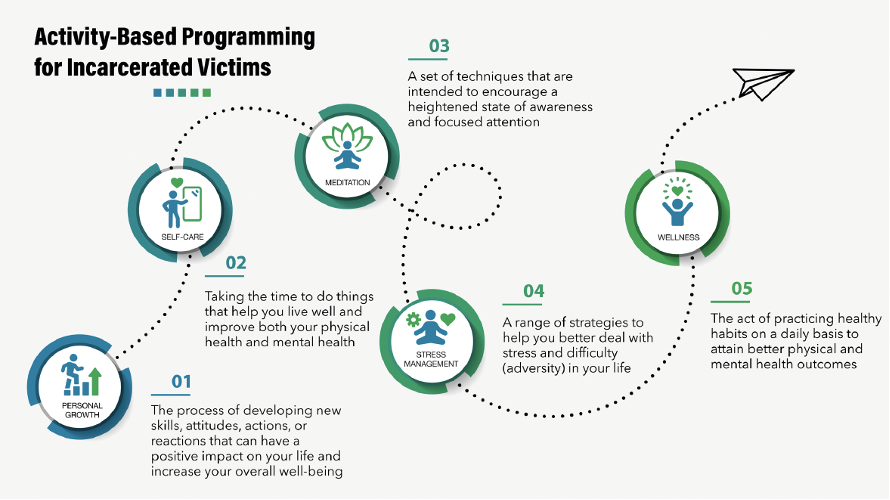

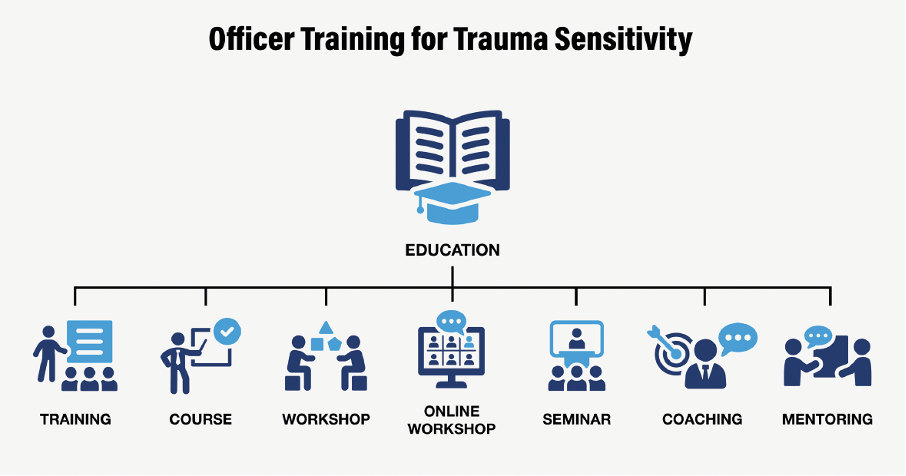

Jails are also particularly poorly positioned to provide proper health care. In fact, local jails tend to offer fewer services and programs overall than prisons do, and because most programs are designed for the larger male population, women may not even have access to programming that’s available to men in the same jail. Women coming into the jail system with substance abuse issues or behavioral health challenges may be significantly challenged in the jail setting.

Furthermore, even among women, incarceration is not indiscriminate, and reforms should address the disparities related to LBTQIA+ status, race, and ethnicity as well. A 2017 study revealed that one-third of incarcerated women identify as lesbian or bisexual, compared to less than 10 percent of men. The same study found that lesbian and bisexual women are likely to receive longer sentences than their heterosexual peers, and more likely to be put into solitary confinement.

Although the data do not exist to break down the “whole pie” by race or ethnicity, Black and American Indian or Alaska Native women are consistently overrepresented in state and federal prisons. While we are a long way from having data on intersectional impacts of sexuality and race or ethnicity on women’s likelihood of incarceration, it’s clear that Black and lesbian or bisexual women and girls are disproportionately subject to incarceration.

Even the “whole pie” of women’s incarceration in the chart above represents just one small portion (17 percent) of the women under any form of correctional control, which includes 808,700 women on probation or parole. Again, this is in stark contrast to the total correctional population (mostly men), where one-third (34 percent) of all people under correctional control are in prisons and jails. Nearly three-quarters of women (73 percent) under the control of any U.S. correctional system are on probation. Probation is often billed as an alternative to incarceration, but instead it is frequently set with unrealistic conditions that undermine its goal of keeping people from being locked up.

Reentry is another critical point at which women are too often left behind. Almost 2.5 million women and girls are released from prisons and jails every year, but fewer post-release programs are available to them — partly because so many women are confined to jails, which are not meant to be used for long-term incarceration. Additionally, many women with criminal records face barriers to employment in female-dominated occupations, such as nursing and elder care. It is little surprise, therefore, that formerly incarcerated women — especially women of color — are also more likely to be unemployed and/or homeless than formerly incarcerated men, making reentry and compliance with probation or parole even more difficult. All these issues make women particularly vulnerable to being incarcerated not because they commit crimes, but because they run afoul of one of the burdensome obligations of their community supervision.

The picture of women’s incarceration is far from complete, and many questions remain about mass incarceration’s unique impact on women. While more data are needed, the data in this new report lend focus and perspective to the policy reforms needed to end mass incarceration without leaving women behind.