Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has shed new light on how incarceration threatens public health. Against the backdrop of another national health emergency—the opioid overdose crisis—people who use drugs have long endured the health impacts of punitive enforcement policies. Black, Latinx, Native American, and low-income communities in particular have shouldered these impacts, and jurisdictions across the country have been slow to shift their overdose responses toward a paradigm that prioritizes solutions outside of the criminal legal system. For policymakers and community members, difficulty locating and tracking local data has only complicated efforts to identify and deploy appropriate interventions.

With support from the Safety and Justice Challenge, the Vera Institute of Justice has released a new digital report, Overdose Deaths and Jail Incarceration: Using Data to Confront Two Tragic Legacies of the U.S. War on Drugs, with data tools and county-level case studies that situate trends in jail incarceration, overdose deaths, and racial disparities side-by-side. While the relationship between jail incarceration and overdose deaths is clearly complex, the data shows that an overreliance on enforcement and incarceration rooted in the War on Drugs has amounted to a patently ineffective strategy for reducing overdose deaths, which sharply increased between 2014 and 2018. In fact, evidence suggests that incarceration itself increases the risk of overdose death by reducing tolerance during periods of abstinence, limiting access to medication-assisted treatment and naloxone during incarceration and post-release, and more broadly disrupting healthcare and social supports located in the community. A recent study from North Carolina found that formerly incarcerated people were 40 times more likely to die of an opioid overdose than the general population two weeks post-release. Additionally, overdose is the leading cause of death among people recently released from prisons and the third leading cause of deaths in custody in U.S. jails.

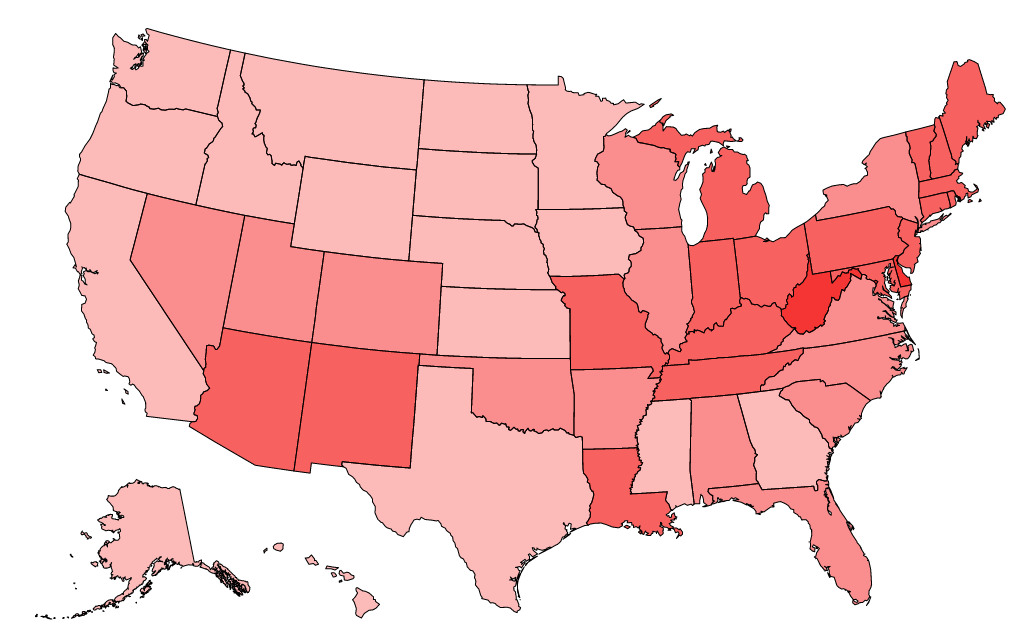

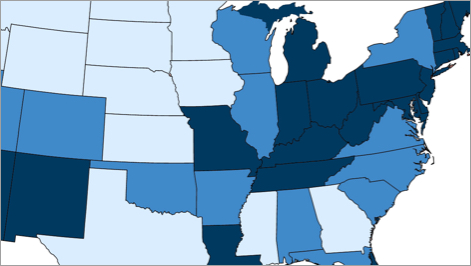

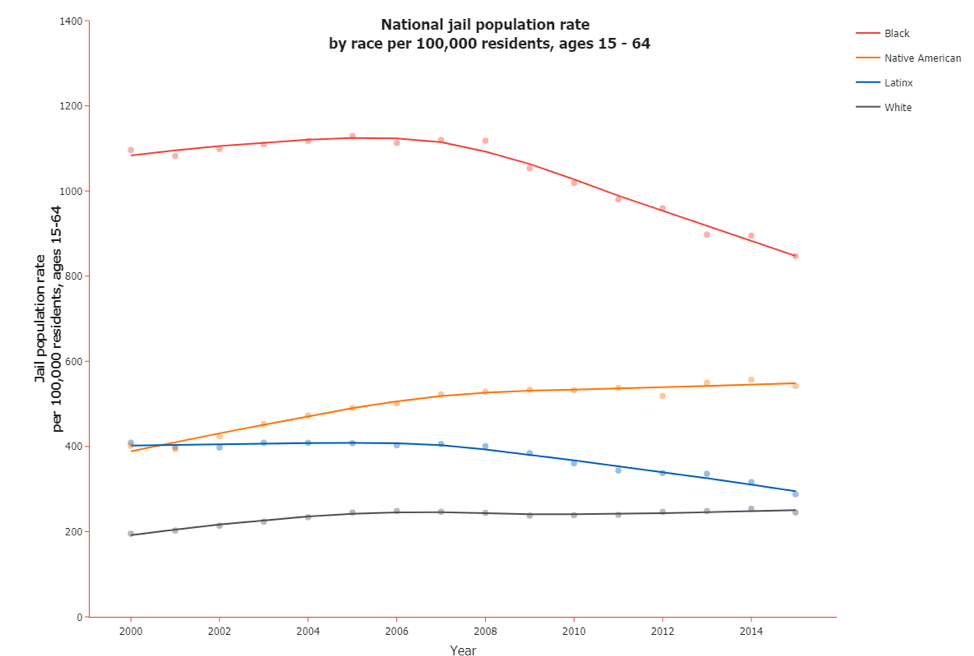

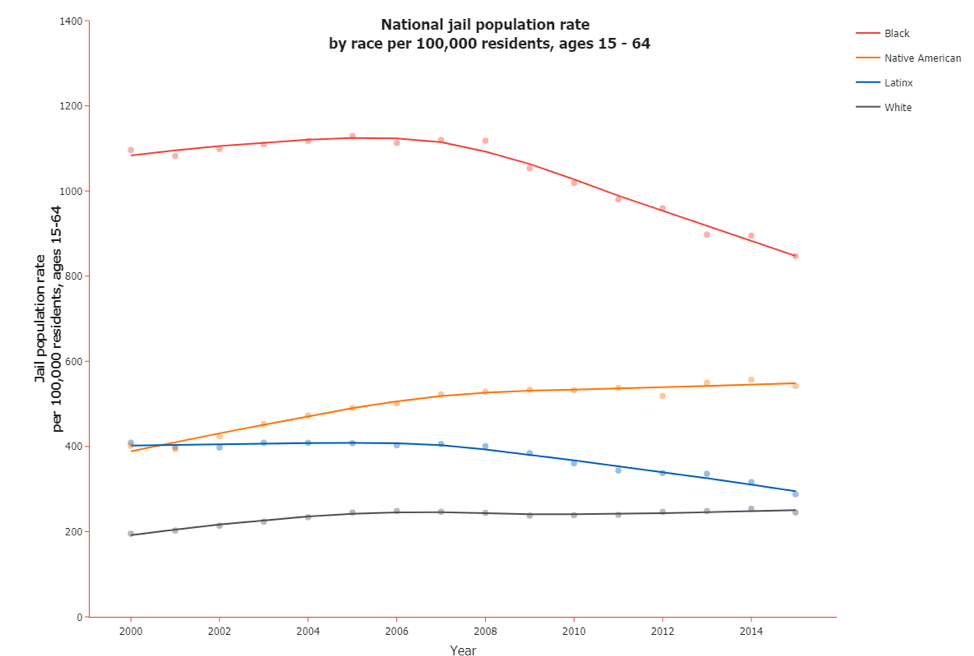

While jail incarceration rates in some cities have plateaued or declined in recent years, small towns and rural areas have seen the opposite trend. Although racial disparities in jail incarceration have declined since 2000, Black, Latinx, and Native American people were still incarcerated at significantly higher rates as of 2015.

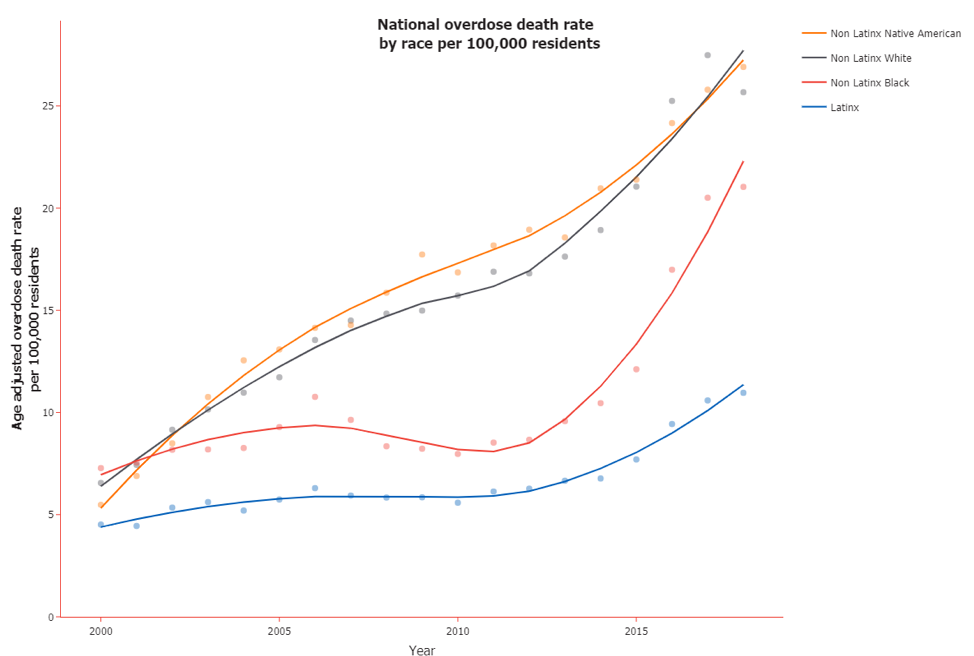

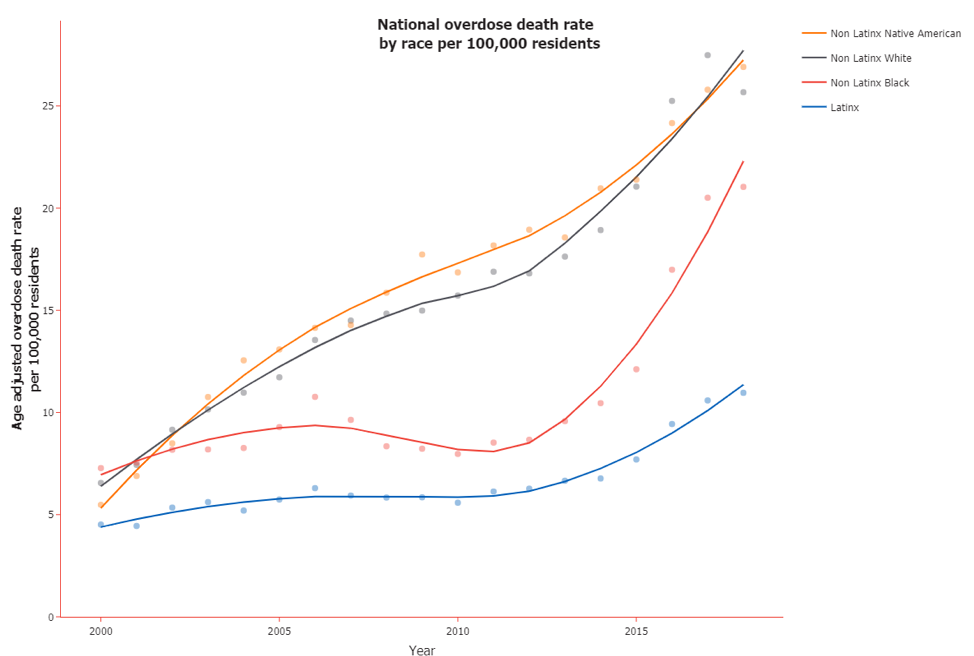

Meanwhile, although overdose deaths have come to be widely thought of as a crisis uniquely endangering white Americans, Native American people have seen similarly high rates of overdose death, and from 2013 to 2018, the rate of overdose death among Black people increased by about 120 percent.

As communities of all kinds have confronted the overdose crisis, they have responded with a wide variety of strategies based in community and criminal legal settings. To examine the interplay between these strategies—and how state and local stakeholders shape them—Vera’s report looks at recent responses in Bernalillo and Rio Arriba counties in New Mexico, and Haywood and Durham counties in North Carolina. In each community, Vera spoke with criminal legal and behavioral health practitioners and directly impacted community members about how they assess the impact of their jurisdiction’s emerging strategies, including naloxone distribution, pre-arrest diversion programs, and the delivery of medication-assisted treatment in jails. While each county’s story is different, they all highlight the potential of reforms that deliver health services outside of criminal legal settings while underscoring the utility of data to aid jurisdictions in evaluating new programs and initiatives.

Above all, these case studies reiterate the need for urgent action in order to save lives. Vera’s report offers guidance for jurisdictions responding to the ongoing overdose crisis, including the following recommendations:

- Programmatic and policy responses should account for historical and present-day inequities in our criminal legal and behavioral health systems. New strategies should be designed to actively address racial and ethnic disparities in criminal legal system involvement and access to community-based health and social services.

- Resources and responsibility for handling problematic drug use should shift toward community-based harm reduction and treatment services. In addition to being ineffective, criminal legal responses like arrest and incarceration can be tremendously harmful for people with substance use disorders, and criminalization itself further stigmatizes people who need help and support.

- Until responses to the overdose crisis are moved to community settings, the harms associated with criminal legal system involvement should be minimized by ensuring police use their discretion to divert people with substance use disorders to appropriate services. Jails should facilitate access to medication-assisted treatment for those who need it both while in custody and post-release. Harm reduction services should also be made widely available post-incarceration as well as to those at risk of criminal legal system involvement.

As communities face COVID-related budget cuts and weigh the merits of response strategies on a continuum between community-based harm reduction and jail-based harm by punishment, they must stay vigilant and follow the data.