Courts Featured Jurisdictions Substance Abuse May 22, 2020

It’s time for criminal justice professionals to reconsider whether and to what extent leveraging a jail or prison sentence is necessary to effectively engage people in behavioral health treatment – or, for that matter, in pretrial services, or parole and probation supervision.

Indeed, the cudgel of incarceration or reincarceration for non-compliance has long been seen as a staple of court-based treatment. But what if that assumption – or at least the field’s overreliance on it – is wrong? Not just from a values perspective, but empirically?

In the spirit of the Safety and Justice Challenge, which is seeking to reduce the use of jail across America, my colleagues and I recently published a brief called “The Myth Of Legal Leverage?”, which explores this question further. Drawing on various bodies of empirical research, the paper posits that relational factors are likely the best and most salient predictors of good outcomes – from recidivism reduction to sustainable recovery.

Strikingly, this argument resonates more broadly across the sciences (e.g., epigenetics, interpersonal neurobiology, attachment, post-traumatic growth, etc.), where there has emerged an elegant consensus about how people change. From our earliest moments as infants and throughout the course of our lives, our capacity for change turns on our access to good, supportive relationships.

Consider the oft-cited “still-face experiment”, where a mother plays with her baby, and then unexpectedly stops responding to the baby with a still face. You can watch it being conducted by Harvard researchers here. The baby very quickly picks up on the mother’s non-engagement, and uses all her abilities to try get the mother back. She smiles, she points, she cries, seeking to get her mother to respond. In just two minutes, when babies don’t get a normal reaction, they feel the stress of the experience, and lose control of their bodies due to the overwhelming and destabilizing anxiety.

It turns out that people retain this sensitivity to—and constitutional need for—intersubjective connection their entire lives. Even the brain of a person who has experienced severe abuse and neglect can still “rewire” in a positive and healthy way once it finds a secure, healing relationship. All of these developments point to the fact that we’re relational beings, and that relationship is a space where we can overcome obstacles in our past and enable us to heal and thrive in the future.

Admittedly, centering relationship marks a challenge to the whole criminal justice field, to shift from a model that pathologizes people, and seeks to control them, to one that values them as human beings that need help and support. Among other things, we will need a seismic culture change to make it happen.

But if we listen to people with lived experience with the criminal justice system, we repeatedly hear that being treated on a human level, in a collaborative and empathic way, and in a way that affirms their ability to overcome challenging life circumstances, is absolutely key to their success.

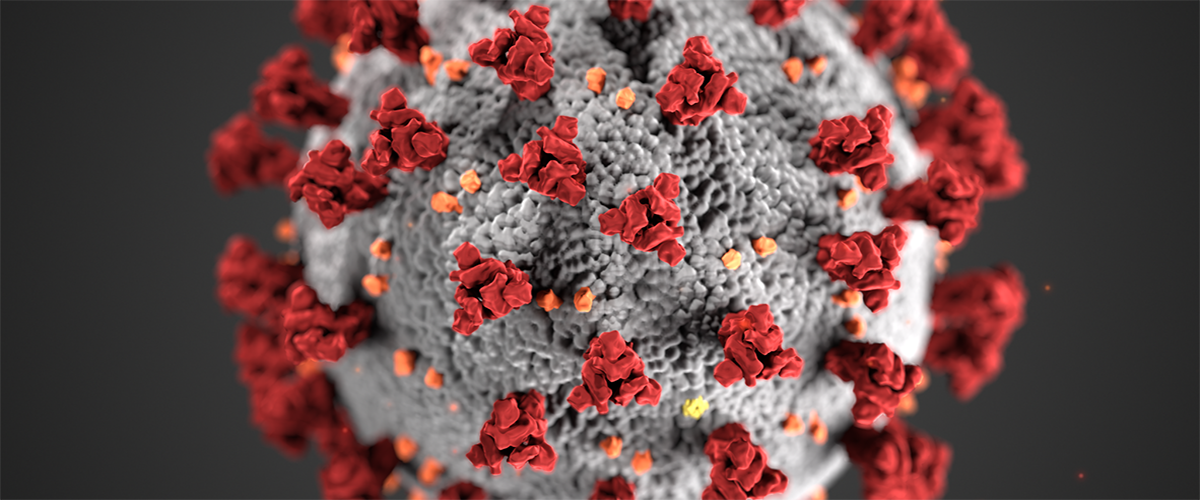

Since the completion of “The Myth Of Legal Leverage?”, we have witnessed significant reductions in the use of jail due to COVID-19. As we gaze ahead to a post-COVID-19 justice landscape, many of us are wondering whether and how we might sustain—or even accelerate—these reductions. Is this moment a proof of concept for a country that can safely thrive with far less incarceration? Will we make the necessary investments in community-based and-led preventative programs to keep people out of the justice system in the first instance? Will we take an unflinching and intersectional look at how system actors exercise their discretion to incarcerate? For folks with more acute behavioral health needs, can we effectively prevent a “third wave” of institutionalization by finally creating a comprehensive and equitable continuum of outpatient services (in lieu of psychiatric and correctional institutions)?

While there are rarely easy answers, there is little doubt that a finer realization of justice in America will demand a deeper appreciation of relationship and our shared humanness.