Reentry Victims April 1, 2024

Reentering the community after incarceration is a complicated, lengthy process, made more difficult by system failures and lack of support and services. Many survivors have specific needs, but these are rarely considered in reentry programs. Experts suggest making the process more trauma-informed and centering the needs of survivors.

The National Center for Victims of Crime recently convened a group of experts with lived experience with victimization and incarceration to discuss how to make the reentry process more trauma-informed. We want to extend a special thank you to Tanisha Murden, Rylinda Rhodes, and Jason Witmer for their participation, which was essential to the report they co-authored on the subject, and the recommendations it provides.

Key Takeaway 1: Every person is different and has different needs related to their past trauma.

Trauma can result from exposure to emotionally disturbing or life-threatening incidents that have lasting effects on a person’s functioning and well-being. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, up to 60 percent of adults experienced traumatic events during childhood, while incarcerated individuals report an average of at least five traumatic childhood experiences. The environment to which people are exposed while incarcerated is also inherently traumatizing, with appalling conditions like overcrowding, solitary confinement, and exposure to violence. These factors can contribute to a post-incarceration syndrome like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), making it difficult for formerly incarcerated individuals to meet their basic survival needs.

Trauma can also lead to negative outcomes as people reenter society after incarceration, such as technical parole violations resulting in a return to jail or difficulty adjusting to work and social situations. This all highlights the need for trauma-informed reentry services to support individuals in healing and successfully integrating back into society. When people who have been incarcerated have unaddressed trauma, they may experience a range of serious negative outcomes. Meanwhile, trauma-informed reentry services allow people to make mistakes and be imperfect.

Key Takeaway 2: Centering families and children with wraparound support

Family connections are crucial for successful reentry post-incarceration. They provide emotional, psychological, and practical support while minimizing the negative impact of parental incarceration on children. Support from family members aids in community reintegration, reduces recidivism, and acts as a primary source of financial and emotional assistance. Increased visitation, especially close to an individual’s release, has been shown to delay recidivism.

However, families dealing with incarceration face various challenges like separation, economic strains, and social stigma, which can adversely affect children’s outcomes in the long run. Positive family backing during reentry is essential, though it can strain families emotionally, socially, and financially. Inclusive case management involving family, friends, mentors, and others in the reentry planning process can help in maintaining vital connections. Peer support from individuals with similar experiences can aid in family reunification, offering guidance and emotional support to both the formerly incarcerated individual and their family. This support system encourages openness about fears and concerns while serving as a beacon of hope for successful recovery post-release.

Key Takeaway 3: Lower barriers to services and consider locating them in the same place.

It is challenging for people leaving incarceration to stabilize their lives on the outside. While some communities have resources for reentry assistance, these resources are often disconnected and do not provide efficient support. Some organizations prioritize outcomes over building relationships, which may result in re-traumatization. Reentry centers offer support for various needs including housing, employment, transportation, substance use and mental health treatment, and medical care. The effectiveness of these services is heightened when provided by individuals who have successfully reintegrated into society themselves. These individuals understand the daily challenges of reentry, which is crucial in cases where the community has changed since the individual’s incarceration. Some community members may not be supportive, making it vital for the reentering individuals to have access to peers who understand both the internal and external challenges they face. Supportive peers not only alleviate feelings of isolation but also serve as role models, showcasing the possibility of success beyond past mistakes.

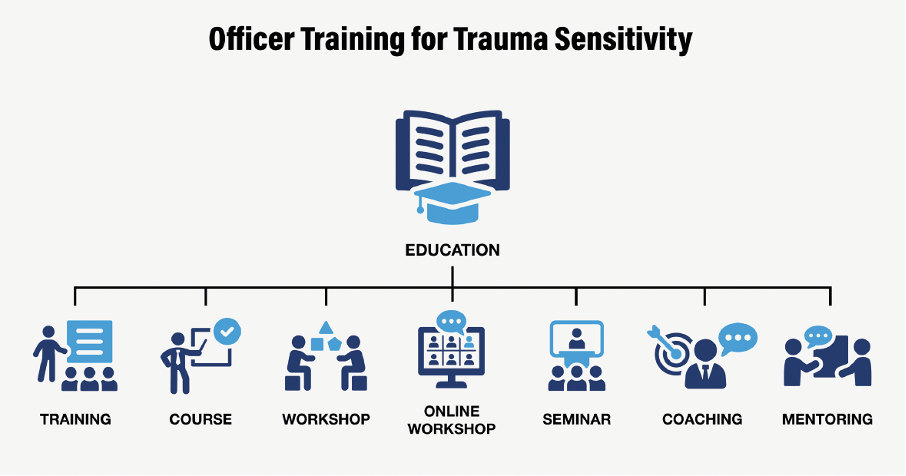

Key Takeaway 4: Infuse knowledge of trauma and how it manifests into every step of reentry.

Training for reentry providers is essential to effectively work with clients affected by trauma. This training should cover the impact of trauma on clients, vicarious trauma on providers, trauma-informed care principles, and specific trauma-informed skills like de-escalation. Ongoing coaching or supervision can further support providers in mastering new trauma-informed skills.

Additionally, service providers should recognize the importance of positive reinforcement in building trust and encouraging success for individuals reentering society. People who are incarcerated often experience trauma, but they also demonstrate resilience. Reentry providers can support them by using case planning and service referrals based on factors that promote healing and resilience. These strategies can include social support, stable employment or school connections, coping skills, and spirituality. Referrals to trauma-specific treatments are crucial for clients with conditions like PTSD or post-incarceration syndrome.

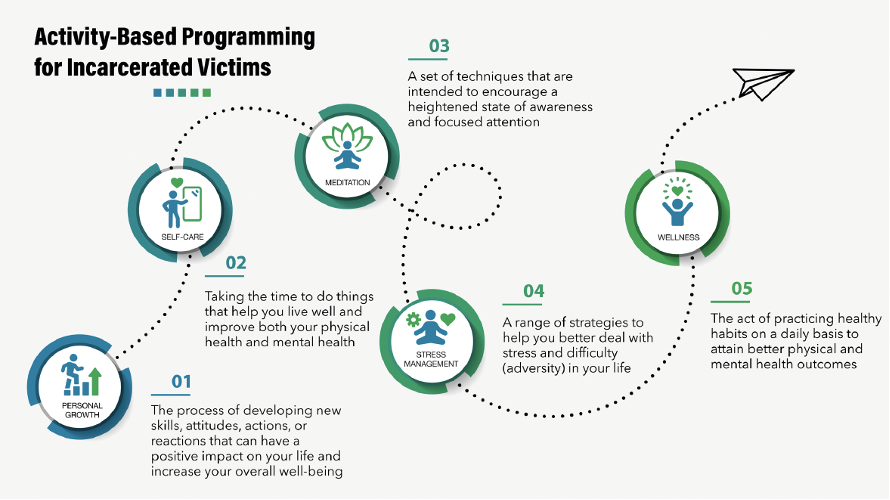

Key Takeaway 5: Implement healing practices into all reentry plans.

The purpose of restorative reentry processes is to aid people in a successful transition home by repairing harm to the extent possible. This aids people returning from incarceration to rebuild support, ultimately reducing recidivism and trauma. Restorative justice can use a trauma-informed approach by recognizing the impact of trauma on both the victim and the person who perpetrated the crime and addressing those effects in the process of restoring harm and repairing relationships. By focusing on the traumatic impact, preventive strategies can be formulated. A trauma-informed restorative justice process involves understanding the prevalence of trauma, recognizing signs and symptoms, responding with empathy and support, and taking steps to avoid re-traumatization.

Highlighting Promising Programs

The report links readers to six trauma-informed reentry programs showing promise across America. While we recognize that implementing these best practices may be a lengthy process, it is well worth the effort. The promising programs we highlight show that integrating trauma-informed approaches will create more sustainable and successful reentry programs, nationwide.