Community Engagement Policing October 12, 2018

Charleston County sustainably reduced our jail population by 20 percent between 2014 and 2019, as part of our work on the Safety & Justice Challenge. The efforts over the last several years underscore the importance of intentional, data-guided policies and practices that engage the community in improving the local criminal justice system. Our work has been done under the auspices of the Charleston County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, where I serve as project director. It’s a collaborative council of elected and senior officials and community representatives that formed in 2015.

In 2019 we launched an initiative to better inform and involve the community. Currently, we have four collaborative working groups, including community representatives and system leaders, working on our next strategic plan.

The workgroups are focusing on: community engagement and disparity; diversion and deflection from the criminal justice system; bond and reentry; and the processing of cases in our court system. Each group is using identified community priorities, system trends and more recent lessons learned—from the pandemic and the growing movement for racial justice—to set goals that will guide reforms to better serve the community in the years to come.

To get here, we’ve traveled a journey. In 2018 we published a report that explored a variety of racial and ethnic inequities locally and nationally, dissected system decision points, and reviewed national examples of reform. We learned by 2017, Black individuals were brought to jail on five single, low-level charges 2.61 times as often as white individuals, a rate that was almost 30 percent lower than it was in 2014 before we started reducing bookings. Still, in 2017 we incarcerated Black individuals more than seven times the rate of white individuals.

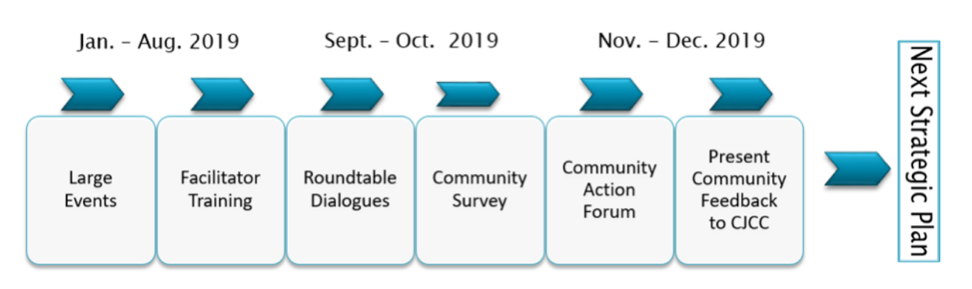

In 2019, the council launched our Dialogue to Change project to expand community engagement while better informing and involving the community in creating our next strategic plan.

We worked closely with community representatives and Everyday Democracy, technical assistance providers to the Safety and Justice Challenge, to form a community coalition that helped to: Build an infrastructure for outreach and meaningful engagement; hold dialogues in constructive spaces to share perspectives on key criminal justice system challenges, foster relationships, and explore ideas for moving forward; and conclude with an Action Forum to determine community priorities for the next strategic plan.

The group identified parts of the community not yet engaged in the discussion, figured out how to include them, and made it happen. We engaged more than 1,000 people in the Dialogue To Change process: more than 450 people came to large community discussions; 101 people came to 11 recurring small group roundtable dialogs; and more than 650 people took part in a community survey.

Here’s a video that gives an overview of the process.

Participants reacted positively throughout, and in the end five broad themes emerged:

- Racial bias and socioeconomic factors, such as poverty and low educational attainment, exacerbate disparity in the justice system.

- The everyday conduct and behaviors of system agents, such as police officers, defense attorneys, prosecutors, and judges, impacts perceptions of trustworthiness, accountability, and transparency of the criminal justice system.

- There are major challenges for individuals returning to the community from incarceration, such as system-related financial obligations, housing, different kinds of treatment, transportation, employment, and regaining community trust.

- Outcomes produced by the local criminal justice system need to be improved.

- Engagement strategies such as transparent reporting, public forums, and community conversations are helpful in improving the local justice system.

The community survey also showed common perceptions of the local criminal justice system: People agree that improvements are needed, have concerns over safety, and want to know more. People want more to be done to improve fairness and address disparities, bonding practices, the time it takes to bring cases to justice, and recidivism.

At the action forum, we identified these priorities:

- Increase education, training, and awareness for justice system stakeholders

- Special trained units for special populations (mental health)

- Training (sensitivity), substance abuse, language/human

- Create more opportunities for community members to become actively involved and engaged

- Community buy-ins

- More involvement between the council and the community

- Build on efforts and activities that the council is doing

- Provide adequate funding for council based on qualitative results

- Focus on the challenges of re-entry from prison and jail

- Establish partnerships and collaborations that will support local justice reform

- Prevention before intervention

- Find community leaders to be the face and voice of this advocacy

Our strategic plan will be finalized this summer and is shaping up to keep community engagement at the forefront. We anticipate it will include a combination of low or no-cost objectives that can be enacted with minimal financial or policy hurdles, as well as more ambitious goals for collaborative reform through community engagement.

—Kristy Danford is the Project Director at Charleston County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council.