Community Engagement Courts Diversion Featured Jurisdictions Interagency Collaboration Racial Disparities April 14, 2022

There is new hope in St. Louis County for people afraid to move on with their lives or engage with the criminal justice system because of unresolved warrants, municipal code violations, or having missed a court date.

The center, which is part of a national effort to lower jail populations in jurisdictions across the country as part of the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC), aids in responding to concerns raised by the Department of Justice (DOJ) about racial injustice related to municipal court practices in its 2015 investigation into the Ferguson Police Department—which is located in the northern part of St. Louis County.

The DOJ commissioned a report in the wake of the 2015 police killing of Michael Brown, which spawned a series of racial justice protests in Ferguson, attracting international attention. The report found that police practices were often unconstitutional and that municipal court practices imposed substantial barriers to the challenge or resolution of municipal code violations. The court also imposed “unduly harsh penalties for missed payments or appearances,” the report said. It also said the law enforcement practices in Ferguson were driven in part by racial bias and that they disproportionately harmed African American residents. So, it is evident that in St. Louis County any efforts to lower the jail population must go hand in hand with intentional efforts towards racial equity.

Minor legal issues are often part of the reason people “tap out” of trusting the criminal justice system. They stop people feeling proactively and collectively engaged with their community’s safety and security. But the new “Tap In Center” aims to rebuild trust between community members and the criminal justice system, with racial equity at its core. The goal is to help people to have a brief conversation and to help them re-engage with court cases and, more importantly, legal assistance.

Data helped with identifying the location for Tap In. It is taking place in the zip code where most African American people in the county’s jail system live. It is also located in a neighborhood that has historically been underserved in transit access, social services, and community supports. The center aims to take a humanitarian approach to the issues that people face when they must go to a court date every month, often for an extended period of time, until their case might be resolved.

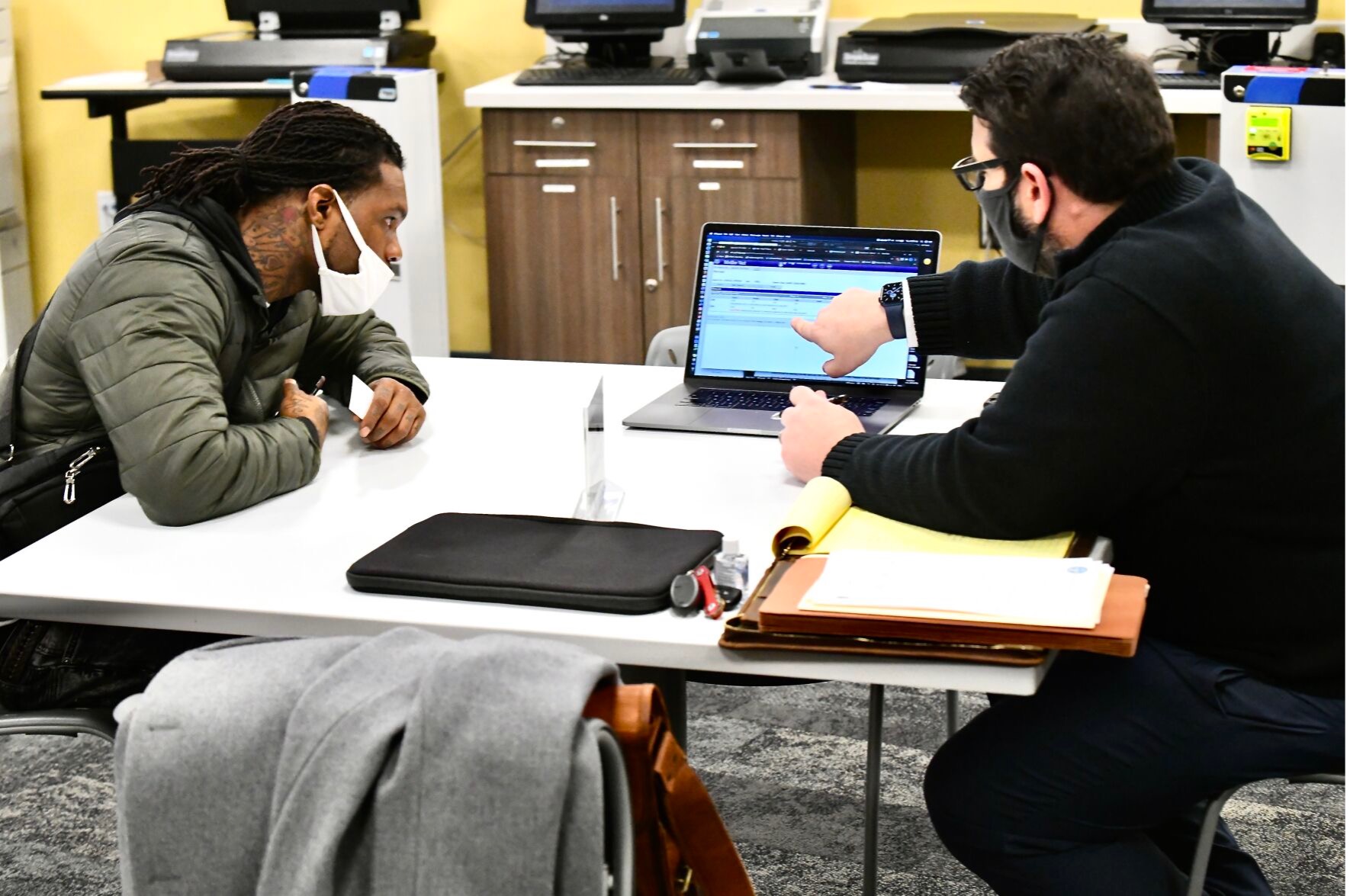

The “Tap In Center” is more than just a place for people to resolve warrants. People can also meet with an attorney, learn their case status, apply for help from a public defender, or even access a cellphone. The center also connects people with other wrap-around services to help them with various challenges in their lives, from temporary housing to clothing to help with food.

Residents have spoken positively about their experience with the center, saying it allows them to continue their lives without fear of bench warrants or fear of arrest for this. Wakesha Cook told St. Louis Public Radio that after getting connected with a public defender and setting up a new court date, “I feel free.”

“When I first got to the center, I was a little nervous since I had this warrant on me, but when I started talking with the people, I was relieved,” said Earnest Holt, another person who visited the center, in an interview with the St. Louis American.

The Tap In Center is a community-based space in a public library. It’s located in a safe, neutral, calm, welcoming spot and is designed to remove barriers and worries that a person might have about going into a courthouse. It welcomes people who come in with warrant issues—people who have historically been wary about engaging with the justice system because they are afraid of, for example, serving jail time.

The center is the result of a partnership between the St. Louis County Library system, The Bail Project, the Missouri State Public Defender, and the St. Louis County Prosecutor, with support from the St. Louis County Courts 21st Judicial Circuit.

Criminal Justice reform strategies in St. Louis County go beyond the Tap In Center. They have focused on systemic case processing, including a population review team, enhanced pretrial reform, pretrial assessment, legal representation, and expedited probation handling. Each of the county’s reform strategies is meant to decrease the disproportionate burden that people of color face in the criminal justice system. St. Louis County is also advised by its own Ethnic and Racial Disparities committee, made up of criminal justice stakeholders, representatives from community advocacy groups, and individuals with lived experiences.

At the time of writing, St. Louis County had reduced the average daily population of its jail by 24% since joining the Safety and Justice Challenge in 2016. Nevertheless, racial disparities do persist. The average daily population of Black people in the jail has reduced by 15% from 2016 to 2021, according to the numbers, and the average daily population of White people has reduced by 41%. Length of stay has reduced for Black individuals who are seeing a 44% decline in the length of stay compared with 41% for White individuals. COVID has slowed progress because of court closures and other related delays. Now that things are reopening, the county is ready to continue its work.

The Tap In Center represents progress and provides motivation for the continued work to be done to address long-standing issues. We hope that other communities across the country will learn from the Tap In Center as they attempt to address their own racial equity issues and more.