Data Analysis Incarceration Trends Jail Populations May 22, 2022

There is great news for people looking to understand how jail populations are changing across the country: The Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) has a new tool enabling anyone to track progress of SJC site jails.

The jail trends tool distills all the progress achieved across SJC sites since the Challenge began. Users can click through to different tabs to explore key trends across SJC sites and can drill down in each of these trends to view them on an individual site basis for a more nuanced local perspective.

We are also planning a series of accompanying briefs over the coming months, which will be available here as they’re released. Each brief will take a more detailed look at specific findings and provide additional context to help explain the trends.

Below is an overview of how users can interact with the tool and a highlight of some of the key findings.

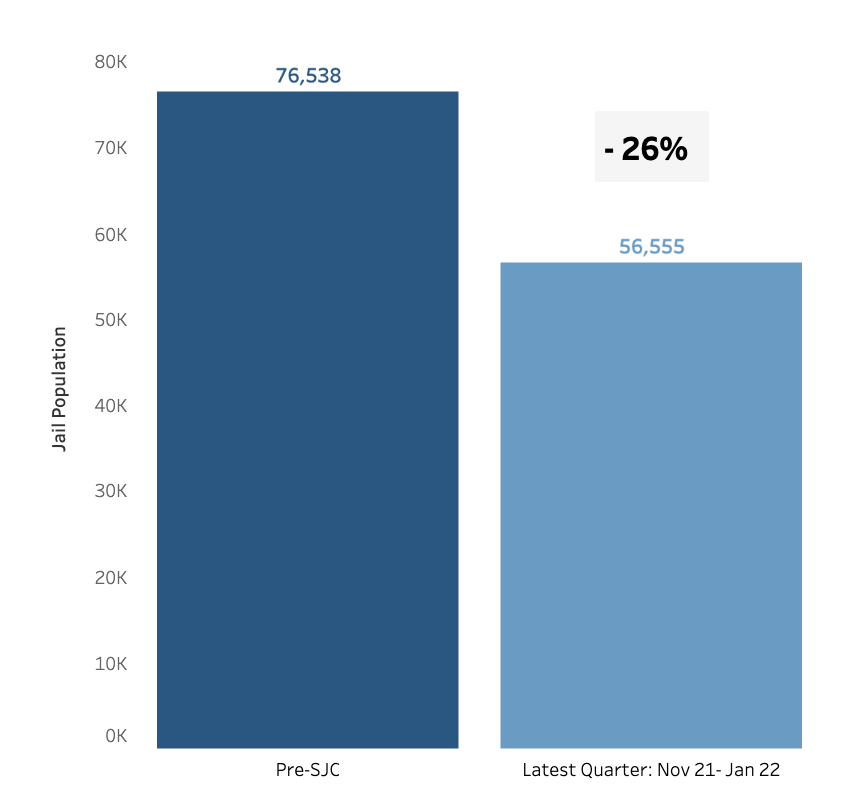

Tracking Jail Populations by SJC site

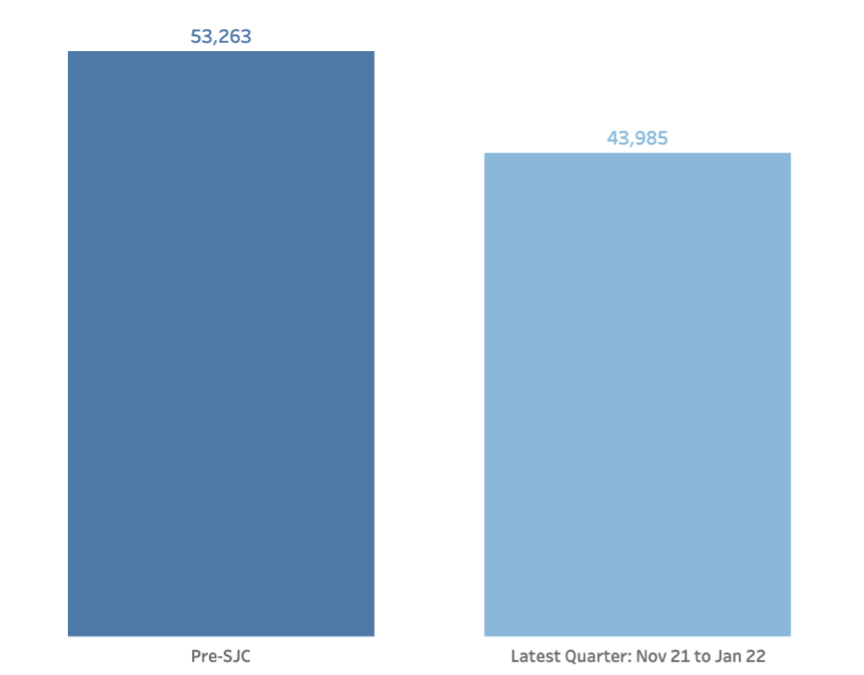

One of the primary goals of the Safety and Justice Challenge is to reduce the misuse and overuse of jails. Users can select a specific SJC community to see how local jail populations have changed since before they joined SJC, to the most recent available quarter. Overall, SJC communities collectively reduced their jail population by 26% since the start of the SJC, resulting in 19,983 fewer people held in jail on any given day. While progress varies across sites, 15 sites reduced their jail population by 15% or more.

Looking at Pretrial Populations

Communities participating in SJC have successfully implemented a variety of strategies to reduce the pretrial jail population and ensure people can stay in their communities while their case is pending. Users can select individual sites to see how their pretrial population has changed. Overall, SJC communities have collectively reduced their pretrial populations by 18% since the SJC began.

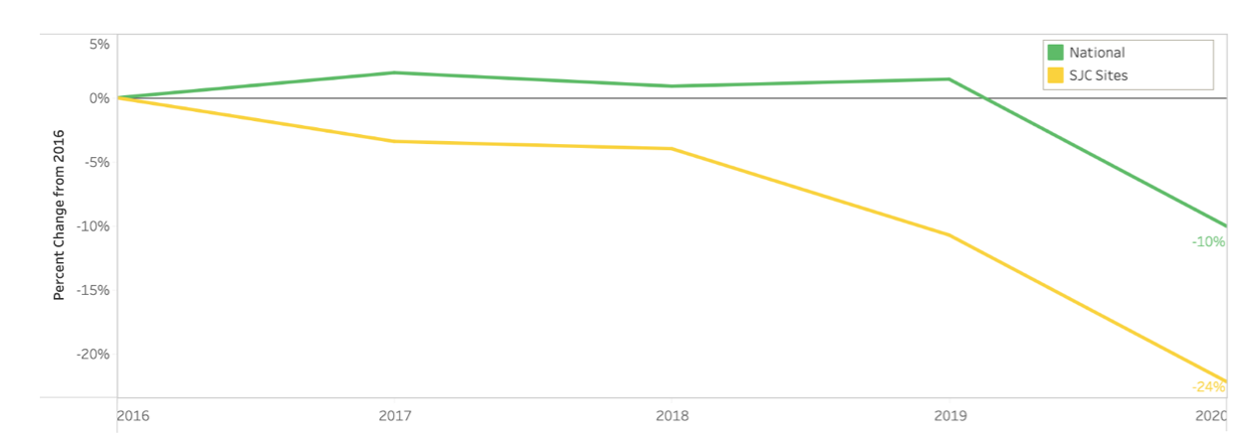

Comparing SJC Sites to National Jail Population Declines

One yardstick for understanding jail population change in SJC communities is a comparison with jail population trends nationally. Overall, the population decline in communities participating in SJC outpaced the national jail population decline prior to the pandemic, and declined at a similar rate during the pandemic. Between 2016 and 2019 the national jail population remained flat. Among SJC communities that began implementation in 2016, jail populations declined by 11% during the period. After the onset of the pandemic SJC sites mirrored the national jail population reduction of around 27% between June 2019 and June 2020.

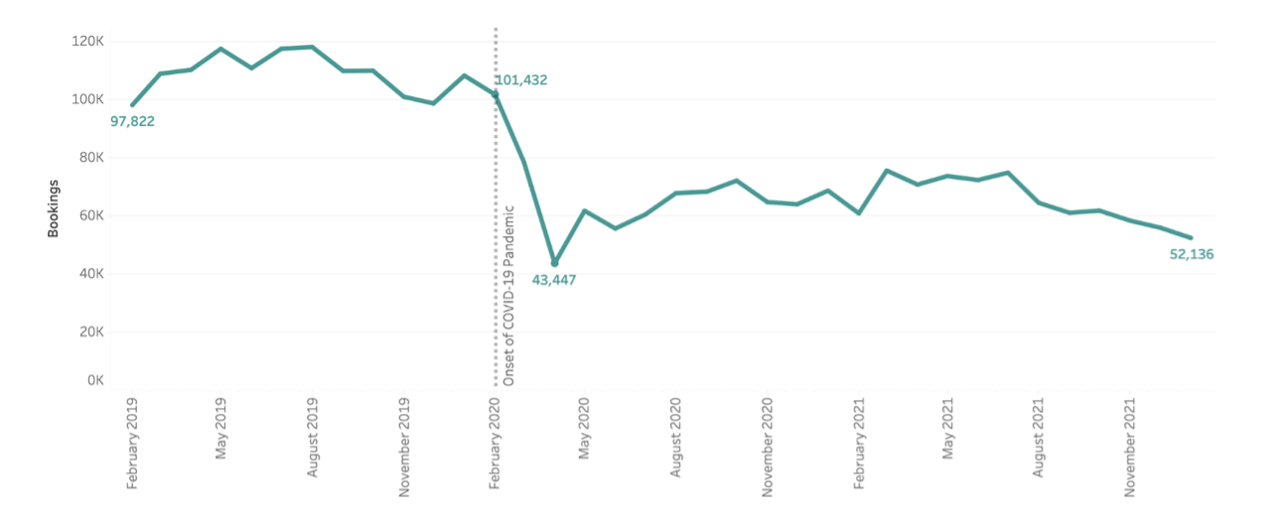

SJC Sites’ Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on jail populations – particularly on jail bookings. In this tab, users can select a community to see how the pandemic affected local jail booking trends. While bookings were declining across sites before the pandemic, bookings dropped substantially, by 57%, between February 2020 and April 2020. Since the low in April, bookings have been rising in most SJC communities. However, as of the most recent quarter, they are still below pre-pandemic levels.

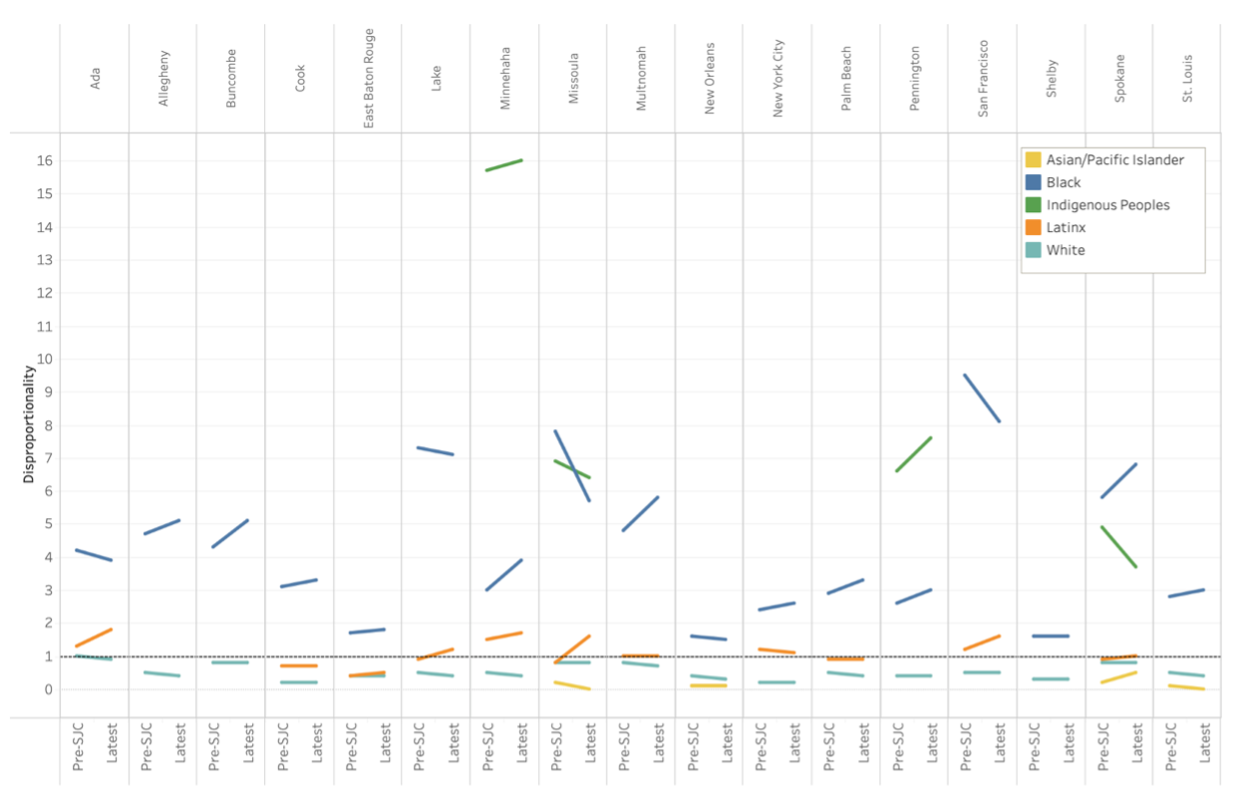

Tracking Racial Disparities

The other core goal of the Safety and Justice Challenge is to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in jail populations. Since implementation, outcomes improved for people of color across SJC communities, but improvements in outcomes for White people outpaced those for people of color. Jail populations declined by more than 15% for Black populations in 10 SJC communities, for Latinx populations in six, and for Indigenous populations in one of four communities. Despite this, declines for White populations were greater. That resulted in persistent or increasing disparities. Users can view disparities for both jail populations and bookings both across SJC sites and at the individual site level.

Future Innovation

Now that the tool is live, we are working with SJC sites and other stakeholders to bring more findings to the public, including trends in length of stay, and further information on how the composition of jail populations has changed over time – in addition to making quarterly updates to the data already publicly available. Please check back regularly to see what’s new!