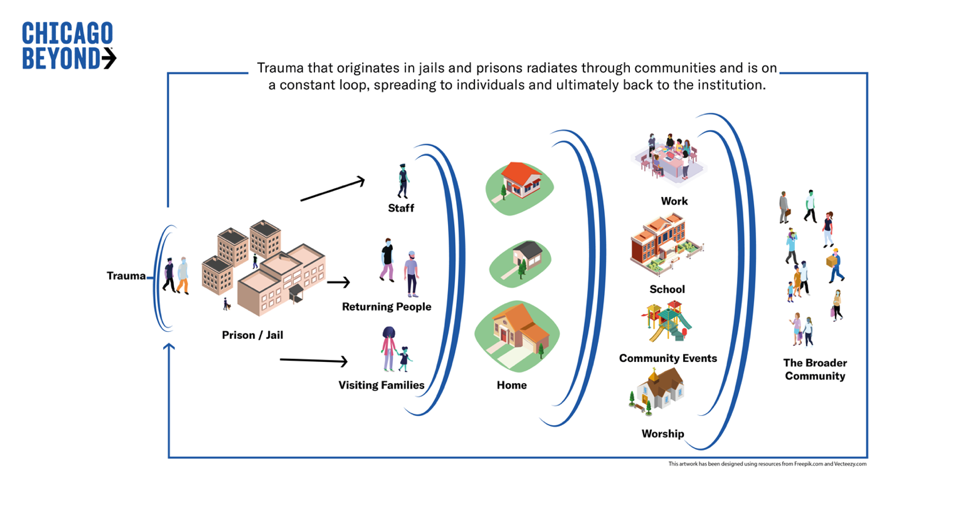

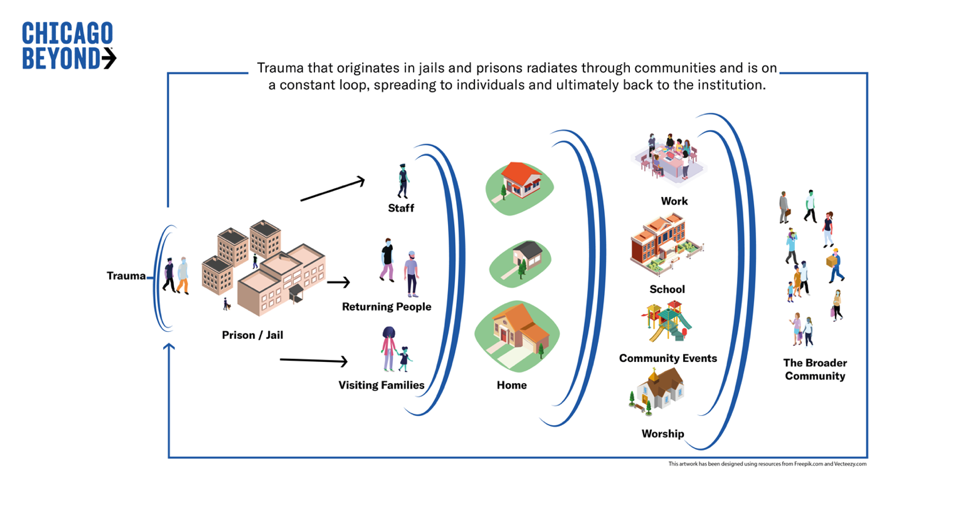

Incarceration is traumatic, and the institutions charged with that function—prisons and jails—often operate in a way that is most traumatic for the people who are incarcerated. But we often overlook the trauma that is also experienced by those who work to staff the jails, and the families of people who are incarcerated.

It’s an opportunity for us to do better, and the scale of the challenge is huge. Every year, people are placed in jails 10.6 million times. On any given day, approximately 2.7 million US children have a parent who is incarcerated, and more than 5 million children have experienced parental incarceration in their lifetime. Approximately 415,000 correctional officers work in our jails and prisons.

Families

Over-policing of Black communities results in a disproportionate number of Black people being sent to jail for low-level offenses. My own father was arrested for marijuana possession when I was growing up in a small town in North Carolina, and he ended up going to jail and then to prison for a couple of years.

As a child, you never forget the experience of police officers hauling your father off. You do not forget having to interact with your father through a piece of glass. They are links in the chain of trauma that lie embedded within a person. And it radiates through communities. Yet, these communities have no pathway to power when it comes to the policies and practices of the institutions responsible for the safety of their loved ones. That must change. There must be a shift in power from correctional leaders to community members when developing and overseeing policies, practices, training, and environmental conditions within these institutions.

Image credit: Chicago Beyond.org

Staff

I ran the jail in Chicago, Illinois, otherwise known as Cook County Jail, as warden, for several years. I was one of the first clinical psychologists in the country to run a correctional institution. My focus was to use my training to instill humanity in the institution, but we don’t talk about how people are traumatized by the experience of incarcerating other people.

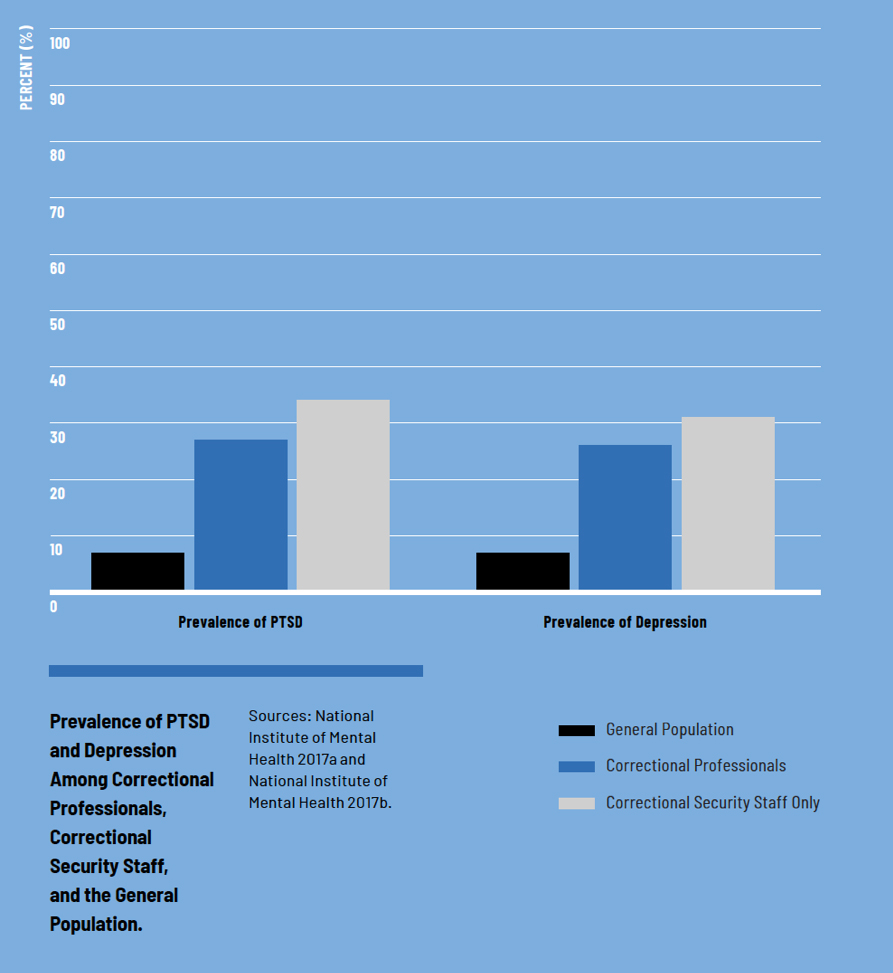

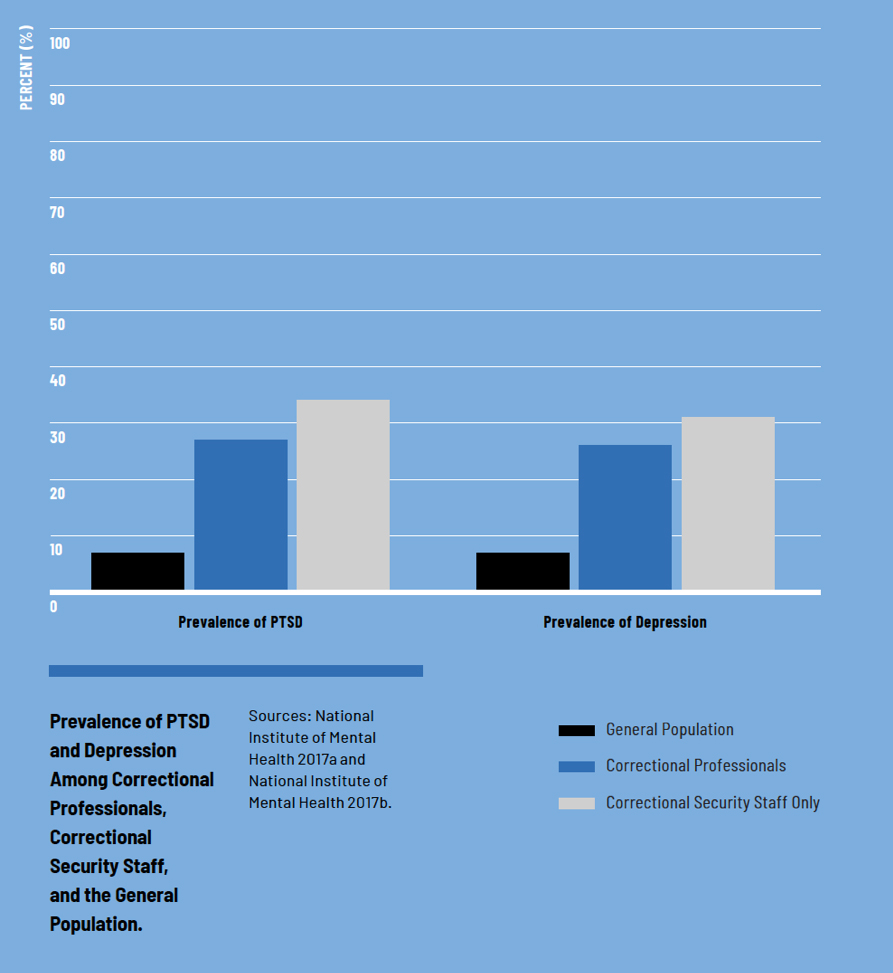

The numbers are stark.

When you talk about such trauma the attitude, historically, towards jail and prison staff is, “Suck it up. You signed up for this.” But the problem is that compartmentalizing the trauma just leads it to bleed out in other areas of your life.

A person’s partner might say, “you are snapping much more often.” Or point out that you are not the same person you used to be. It took me a while after I left the job to realize that it is not normal to sleep only two hours a night. It is not normal to be constantly ready for your phone to ring. To feel on the edge of your seat worrying about the next crisis. It takes a significant toll on a person, and it is hard to see the woods for the trees when you are in the thick of it.

People who work in the system are sometimes a little nervous when I bring this stuff up. They do not want to risk opening an emotional Pandora’s box by talking about the trauma they might be suppressing. My response is that the box is already open. The effects are already exerting themselves on you, on your family, and on those you signed up to keep safe.

Interconnected Humanity

At Chicago Beyond, we have started an impactful conversation about all this. In my reflection on my time at Cook County Jail, one of the big things we realized was that if correctional staff treated the people who were confined and their families with humanity, they could also see the humanity in themselves. We partnered with the Cook County Sheriff’s Office to develop family-friendly visitation, because helping people who are incarcerated hug their children for the first time in years is humanizing for everyone. People had strong emotional reactions to working in visitation, and we talked about the implications. We also acted on them at the policy level.

We have produced a report on this at The Square One Project, called Harm Reduction at the Center of Corrections. It includes a first-of-its kind framework for correctional leaders to better support the people detained, staff, and the families of both. It provides recommendations for correctional leaders centering on safety, transparency, agency, asset-based approaches, and interpersonal connections for these three groups to minimize the harm created by jails and prisons.

The project of harm reduction is critical from this perspective. There are many specific measures that can be used in correctional settings to decrease harm, including incarcerating fewer people. But the key ideas center around one core concept: correctional leaders promoting human interaction that instills humanity.

We are talking about imagining a future for justice and public safety that starts from scratch — from square one — instead of tinkering at the edges or cherry-picking cordoned-off areas for reform. To do so, we need to get to the root of the problem: decades of neglect around communities with chronic poverty and the twin crises of ingrained racism. That begins with drastic systemic change. It requires addressing the specific harm we have experienced as people and extending the compassion we give to ourselves to other people – all people.