COVID Crime Data Analysis Jail Populations March 21, 2023

New research findings directly address recent claims about the role of criminal legal reforms in violent crime trends.

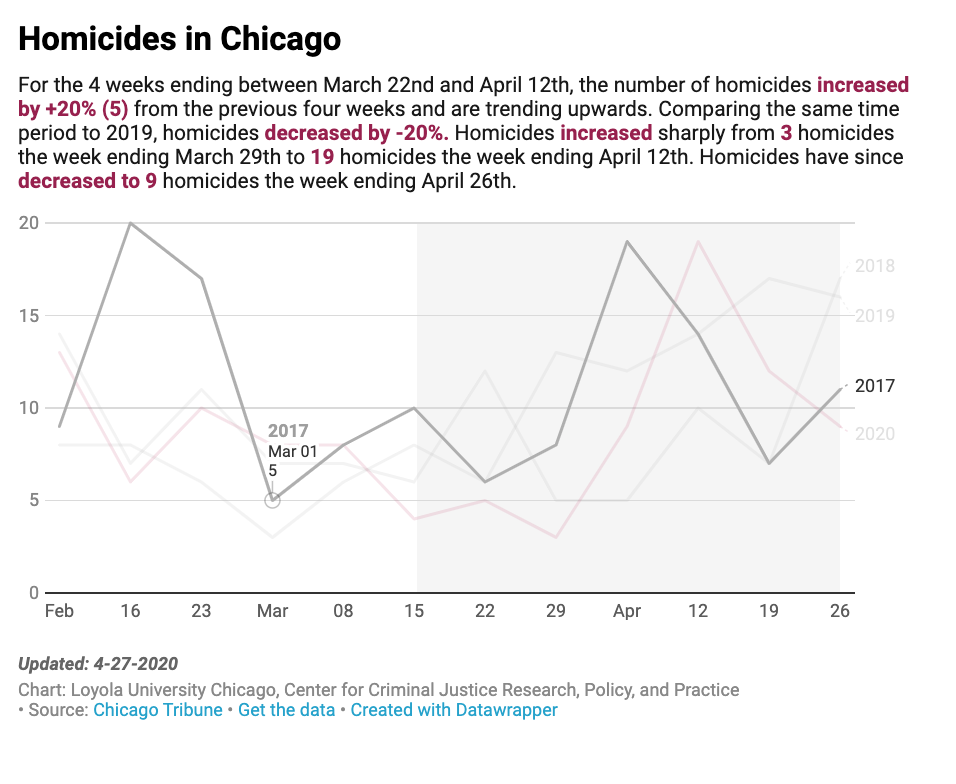

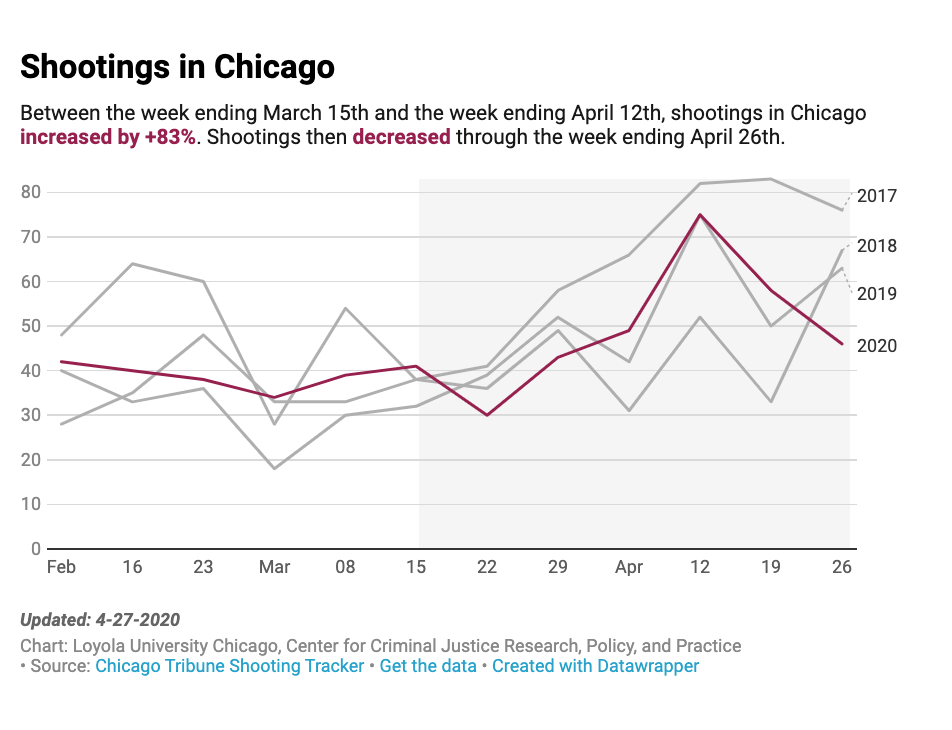

In response to the rapid spread of COVID-19, jails across the country implemented emergency strategies to reduce jail populations and mitigate the virus’s spread. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, public data show that violent crime and homicides have increased nationally. These increases have put a spotlight on criminal legal reform efforts, with growing public discourse in some political and media circles suggesting that reforms are causing these increases.

These claims often speculate that people released due to efforts to reduce jail populations are responsible for new violent acts committed. They make for attention-grabbing headlines but are not backed by any evidence-based research. They do not acknowledge the concurrent complex web of pandemic-related social and economic strains, or the fact that homicides increased in many major cities that did not enact progressive jail reform efforts.

The recent uptick in violent crime is real, but the increase is reflected across the country. This includes jurisdictions with progressive and traditional prosecutors, and cities and counties pursuing jail reform and those maintaining the status quo.

Digging Into the Data

Data collected from cities and counties participating in the Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC), a multi-year initiative funded by John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, is the basis for one of the only analyses exploring these questions in depth on a national, multi-site scale.

To explore whether increases in violent crime were related to both the pandemic and criminal legal reforms, The CUNY Institute for State & Local Governance (ISLG) analyzed pre and post pandemic jail data on individuals released from jail on pretrial status, defined as people released from physical jail custody while their trial is ongoing, pending the disposition of one or more booking charges. The analysis shows how many individuals released from jail on pretrial status were returned to jail custody within six months (referred to as a rebooking).

The findings from this analysis, using individual-level jail admissions data from March 2015 to April 2021, show that reforms focused on releasing people from jail on pretrial status did not appear to drive recent increases in violent crime. In contrast, ISLG found that for SJC cities and counties:

- There is no apparent correlation between declines in jail incarceration and increases in violent crime through COVID-19.

- Most individuals released on pretrial status were not rebooked into jail. This has remained consistent over the years.

- Of the small percentage of the individuals rebooked into jail, it was very rare to return with a violent crime charge and exceedingly rare to return with a homicide charge.

It is likely that many complex social and economic factors related to the pandemic contributed to the overall increases in violence, and particularly in homicides, that occurred across cities in 2020. However, findings from this analysis suggest that evidence-driven criminal legal reforms were not among those factors.

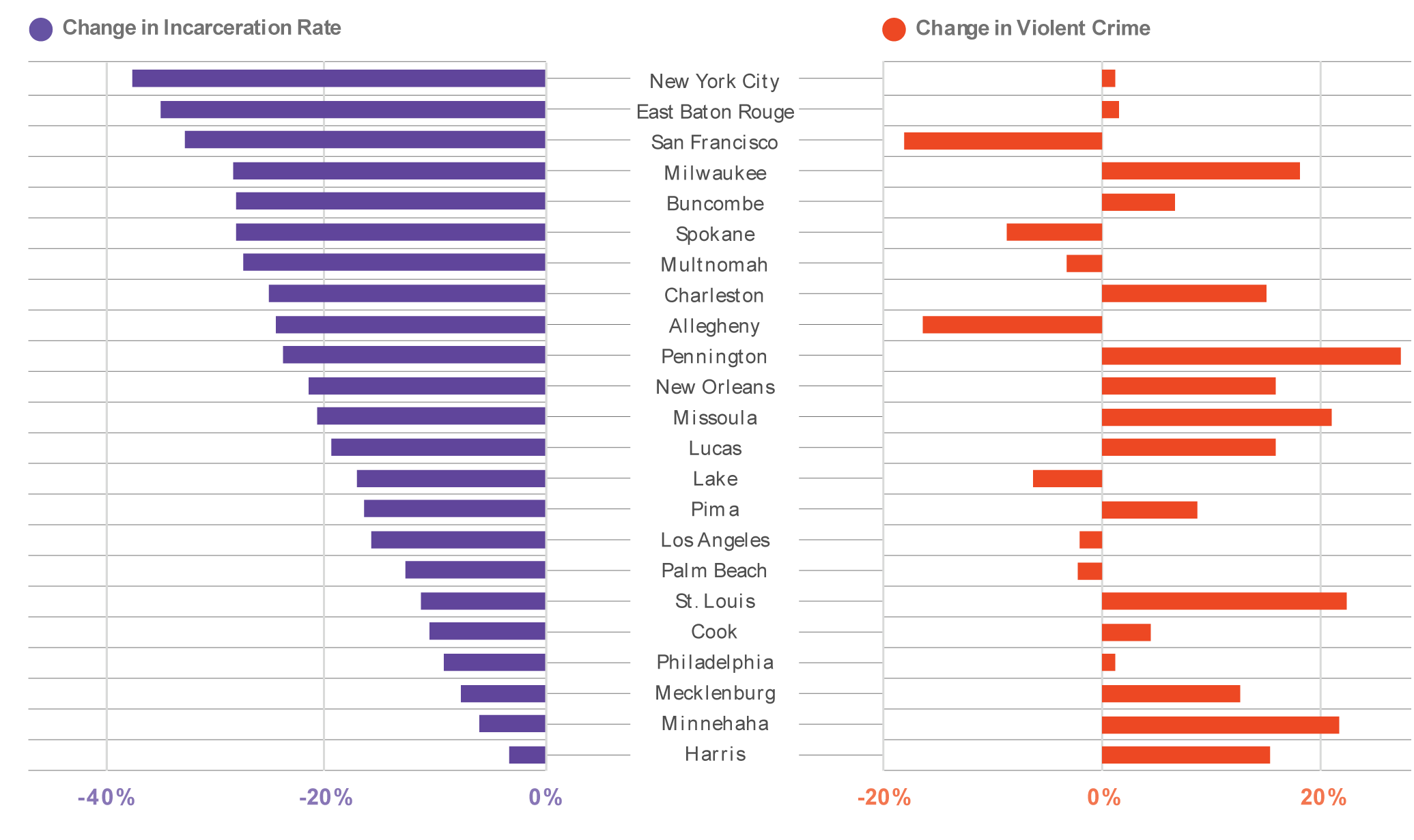

There is no apparent correlation between declines in jail incarceration and increases in violent crime through COVID-19

Following the implementation of SJC strategies to reduce local jail populations, SJC cities and counties’ incarceration rates declined at a faster pace compared to the national average, yet trends in violent crime were similar to the national trend. Violent crime was down across SJC sites and the nation between 2017-2019, only increasing during the pandemic in 2020.

Further, when looking at data for individual SJC cities and counties, all 23 SJC cities and counties decreased their incarceration rate between 2019 and 2020, when the pandemic emerged. However, changes in violent crime varied across cities and counties, and larger decreases in the jail population were not always associated with increases in violence.

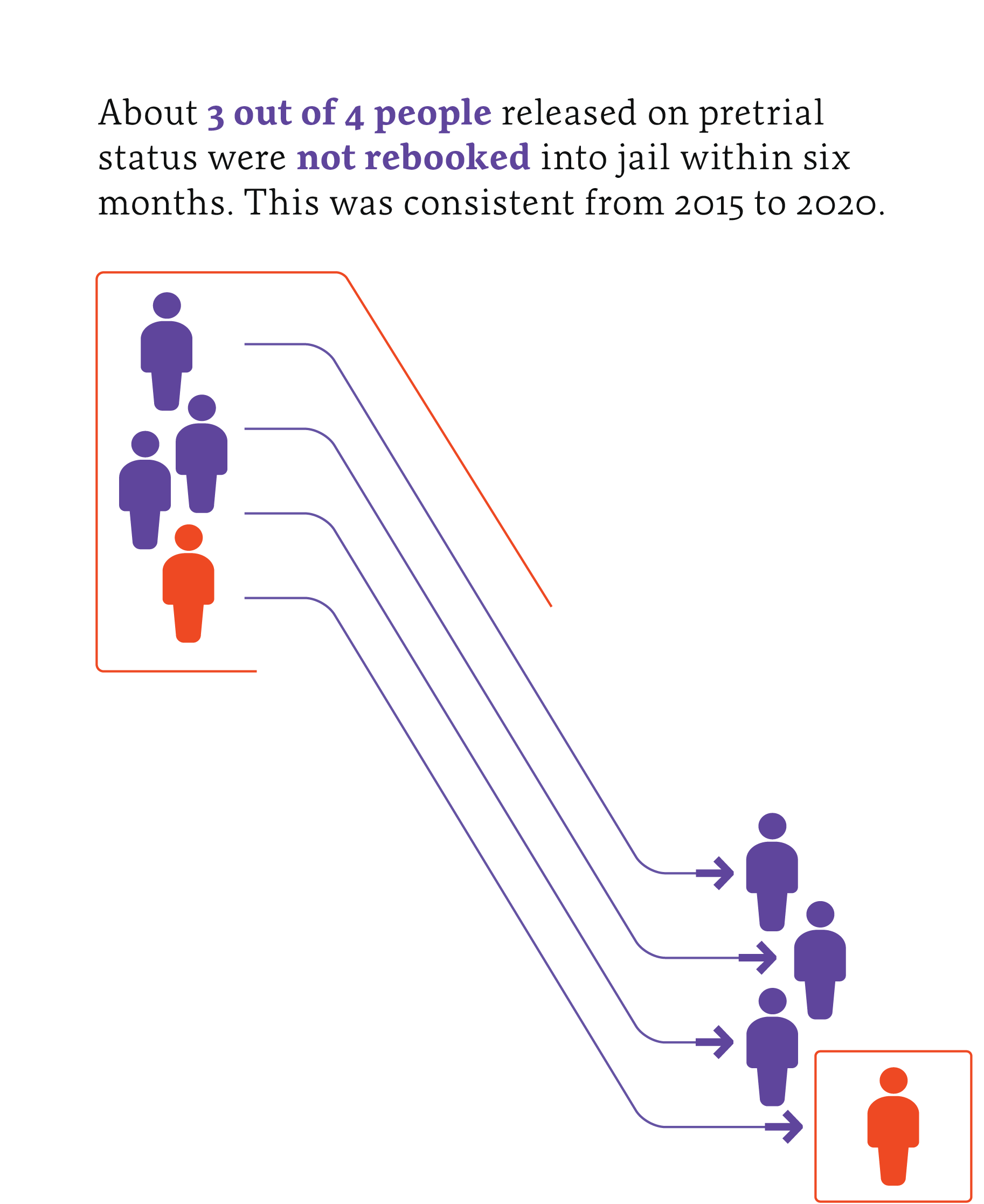

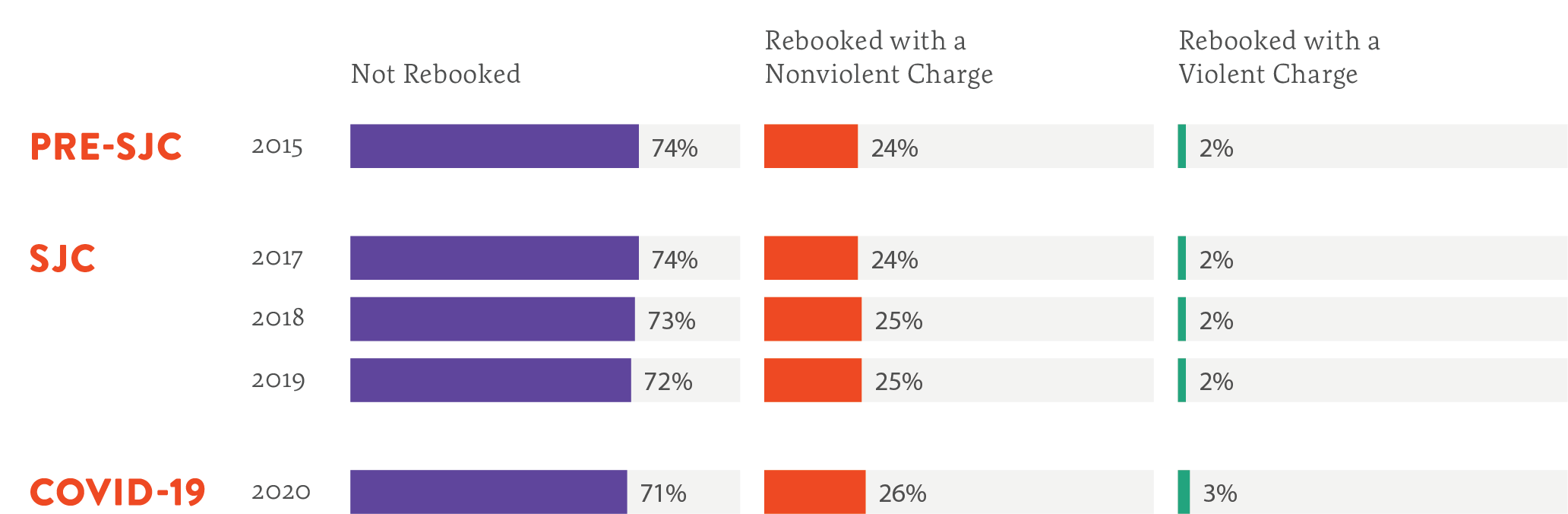

Most individuals released on pretrial status were not rebooked into jail and very rarely were they rebooked on a violent crime charge, which remained consistent over the years

Using data from local jails in SJC cities and counties, ISLG followed people released on pretrial status and measured whether they were rebooked into jail within six months of the release.

This analysis showed that across five years from 2015 to 2020, about three out of four people released on pretrial status were not rebooked into jail. In other words, people released from jail

were no more likely to return to jail after the implementation of SJC or CO

VID-19-related strategies for reducing jail populations. Over time, a very small share (two to three percent) of people released on pretrial status were rebooked within six months for a violent charge, a rate consistent before SJC implementation in 2015, during SJC implementation from 2017 to 2019, and through COVID-19 in 2020.

While violent crime may have increased in some SJC cities and counties overall, people who were released from jail while their criminal cases were pending were not the cause of these increases. The overwhelming majority of people released on pretrial status between 2015 and 2020 (over 96 percent) did not return to jail on a violent crime charge.

The rebooking rate for homicides specifically was even rarer: over 99% of people released on pretrial status were not rebooked on a homicide charge within six months. This was consistent from 2015 to 2020.

The Need for Evidence-Based Research instead of Attention-Grabbing Headlines

This study adds to the growing evidence that advancing equitable and thoughtful criminal legal reform is possible without compromising public safety. To suggest otherwise without evidence undermines the harms of incarceration on individuals, their families, and communities. Such discourse also distracts from genuine attempts to understand the true causes of rising violent crime, particularly homicides. More research is needed to unpack the increases in violence during a time of even more pronounced disparity in the U.S. as we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.