Interagency Collaboration Jail Populations Veterans November 9, 2023

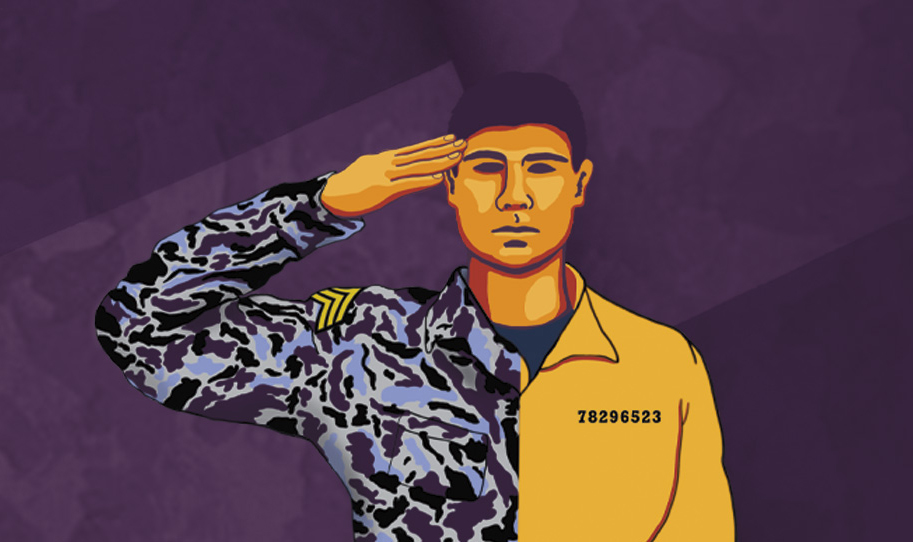

Each year roughly 200,000 active-duty service members leave the United States military and return to civilian life. While most navigate this transition successfully, many struggle with mental health and substance use disorders, the effects of traumatic brain injury, homelessness, and criminality. One in three veterans report having been arrested and booked into jail at least once, a rate significantly higher than for non-veterans.

People who have served this nation in our armed forces have sacrificed to protect us. It is time for us to better recognize that sacrifice and take steps to ensure our veterans are treated fairly by the justice system. Veterans who encounter the criminal justice system should receive interventions that can help them resume their responsibilities to their families, their communities, and their country.

Last year the Council on Criminal Justice launched a national effort to help make that happen. Its Veterans Justice Commission, on which I serve, is chaired by former U.S. Defense Secretary and U.S. Senator Chuck Hagel and also includes former Defense Secretary and White House Chief of Staff Leon Panetta, the Chief Justice of the Georgia Supreme Court, two formerly incarcerated veterans, and other top military, veterans, and criminal justice leaders.

Our mission is straightforward: to examine veterans’ involvement in the criminal justice system and the risk factors that drive it, and to develop recommendations for evidence-based policy changes that enhance safety, health, and justice.

My fellow members and I have learned a lot since embarking on this endeavor. Above all, we have discovered that despite a patchwork of interventions designed to help veterans across the country, too many are falling through the cracks. Here is one example: while Veterans treatment courts have been a pioneering front-end intervention, just 14 percent of counties operate one, and eligibility requirements for such courts exclude many veterans.

Another challenge is that veterans who become incarcerated lose access to health care from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which prevents them from receiving the specialized treatment they need to address post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other problems. The suicide rate for veterans is approximately 1.5 times higher than the rate among the general population, and it is especially high for veterans leaving incarceration.

In September, the commission released a policy roadmap that encourages the expansion of alternatives to prosecution and incarceration for justice-involved veterans. This blueprint outlines alternative sentencing options that not only recognize veterans’ service, but also consider the fact that their criminal behavior may have been influenced by that service. The options, which include expanded use of pretrial supervision and probation in lieu of a record of conviction or incarceration, are grounded in evidence-based practices. The commission also recommends allowing veterans whose cases are processed through such options to pursue record expungement.

Based on the policy framework a model policy called the Veterans Justice was adopted. This version of the framework will be shared with state legislatures as a blueprint for action on the issue. The policy framework reflects an initial set of recommendations released by the commission in March. Additional recommendations targeting veterans’ transition from service to civilian life will be forthcoming early next year.

As jurisdictions consider this model policy framework, my fellow commissioners and I hope the federal government will incentivize the widespread adoption and effective implementation of these reforms. Many of the framework’s elements will require updating existing systems, training personnel, and conducting ongoing evaluations. Federal funding can serve as a critical resource for jurisdictions pursuing these vital reforms, which will ensure that veterans nationwide can access correctional interventions designed for their specific needs.

I also hope policymakers at the state and federal level consider this disturbing reality: We are prosecuting and imprisoning veterans while denying them the care and consideration they need and deserve. And we are doing so even though their criminal justice involvement is often due, at least in part, to their willingness to fight for their country. As a result, we are not only doing a disservice to veterans, but also jeopardizing the safety of the public they once fought to protect.

The challenge of veterans returning home from wars and landing in the criminal justice system is not new. But our response can be.